By Walter W. Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2017

Thanks to John Winthrop Jr., the colony of Connecticut could rightly be called America’s first scientific research laboratory. One of the leading figures in early New England settlement, Winthrop totally confounds the stereotype of the stern, bigoted, anti-enlightenment Puritan. He was outgoing, tolerant, and passionately committed to deploying science to make Connecticut a godly Zion in the wilderness.

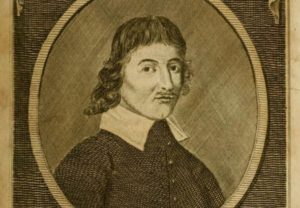

Born in 1606 in Groton, England, the affable Winthrop was a political leader from his arrival in New England in 1631 until his death in 1676. He spent 19 years as the governor of Connecticut. Founder of three towns—Saybrook and New London, Connecticut and Ipswich, Massachusetts—he was also an industrial entrepreneur who oversaw development of three colonial ironworks, two innovative salt works, and a variety of colonial mining endeavors.

He was a skilled diplomat, too, who secured in 1662 an unexpectedly and extraordinarily generous royal charter from the newly restored King Charles II. And Winthrop was New England’s most sought-after physician, to whom requests for medical advice came from as far away as the Caribbean and Europe.

Winthrop’s accomplishments were many and varied, but all were grounded in his commitment to using the early science of alchemy to help get Puritan New England established on a firm and godly economic base. His scientific knowledge was considered so remarkable, in fact, it earned him a place as a founding member—and the first colonial member—of England’s Royal Society—still one of the world’s leading scientific institutions.

We’re not used to thinking of science as an important factor in colonial settlement. Nor are we accustomed to thinking of alchemy as science. Yet in Winthrop’s day many considered that early form of chemistry—a pursuit that blended religion, science, and magic and linked them to practical laboratory research—as the most important and most godly of all sciences. Through pious laboratory experimentation that began with prayer and ended, God willing, with new chemical revelations, alchemists strived to gain perfect knowledge of medicines and to turn impure metals into gold. In the process, they also discovered new and useful chemicals, medicines, production processes, and industrial technologies.

To Winthrop, Connecticut, filled with previously unknown plants, animals, and the abundant land and natural resources England lacked, seemed an ideal site for alchemical discovery. In venture after venture he made his colony a large-scale laboratory for chemical discovery. His most ambitious scheme centered on the town and alchemical research center he founded, which he insisted on calling the “new” London. He recruited alchemists from around Europe to join him there in an effort to use science to improve the human condition. Their godly experiments would be funded with profits from what he believed was a silver mine near present-day Sturbridge, Massachusetts. While difficulties with mining the ore and Indian resistance soon forced alterations to that scheme, Winthrop continued to develop the New London alchemical approach, making it a center for both teaching and administering advanced alchemical medicine.

Winthrop’s lifelong practice of alchemy, which you can read about in my book Prospero’s America: John Winthrop Jr., Alchemy, and the Creation of New England Culture 1606-1676 (The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), transformed Connecticut, just as it transforms our understanding of Puritan New England. From the beginning, even before it was a state, Connecticut was a place of scientific research and innovation and a magnet for both talent and ideas.

Walter Woodward is the Connecticut state historian.