By Kristen Nietering and Charlotte Hitchcock

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

From around the time of World War I through the 1970s, Connecticut proved a magnet for writers and visual artists, particularly those associated with modern artistic and literary movements. The groundbreaking modern art exhibition known as the New York Armory Show of 1913 is seen as the beginning of a new era in the arts in the United States, while the 1970s saw the winding down of a number of branches of the modern movement.

Connecticut was home to a remarkable group of progressive thinkers responsible for positioning the state at the forefront of cultural currents during this exciting period of change. One might think that, as members of a movement intent on rejecting past conventions in search of new forms of expression, modernists would have found an indifferent reception in a state closely associated with traditional values. Yet Connecticut proved a rich environment by offering affordable workplaces, institutional support, and a culturally diverse population open to new ideas. For this reason, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation (Connecticut Trust) has launched a project to identify, document, and promote places important to Connecticut’s cultural development in the 20th century with a particular focus on where novelists, poets, playwrights, and journalists and painters, sculptors, and photographers created their work, or on the places that inspired them. The project is supported by the Department of Economic and Community Development’s State Historic Preservation Office,with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Documenting a legacy of creative endeavor helps us understand and interpret the state’s history. These physical places are a means to locate this legacy. Other purposes for documenting sites include raising awareness of their significance and fostering their appreciation and protection. We are creating an inventory that also encourages us to go deeper and ponder the underlying question of what defines Connecticut as place. What about Connecticut’s physical setting has made it such a powerful magnet for these artists? And how is Connecticut celebrated in the lives, work, home, and studios of the people who worked and lived here?

The project’s identification of what constitutes modern art has been broad: work created by artists as they rejected past conventions and created new art for a changing world. This definition encompasses abstract work. And it also includes the art of the Depression era in which the lives of ordinary people are depicted, the regionalist styles portraying the working landscapes of agricultural, industrial, and maritime areas, and literary work that established new genres of writing such as children’s literature and the literature of nature and environmental conservation (often integrating text and illustration). Our search also includes ways in which the careers of non-traditional artists—immigrant, female, and minority—diversified the body of artistic and literary work.

Architectural historian Rachel Carley’s introduction for the project resulted in the identification of a series of broad themes. These include:

- Connecticut as refuge for European émigrés and for African American and ethnic groups from within the United States.

- The emergence of urban cultural centers in Hartford, New Haven, New London, Norwich, and New Britain.

- The colony phenomenon, an outgrowth of earlier art colonies of the late 19th century.

- Public art of the Depression era and public memorial art.

- The unique evolution of Fairfield County from a rural area convenient to New York City to a suburban region.

- Post-World War II patronage by universities, museums, galleries, and private patrons.

- Evolving genres of children’s literature and of nature and conservation writing, art, and photography.

We have focused on many places where art was created. These include homes or studios of writers or artists, such as playwright Thornton Wilder’s house in Hamden, and artistic/literary colonies such as Russian Village in Southbury [See “Site Lines: Russian Village,” Fall 2013.] As we searched for significance of place to the creative work, we also found site-specific works of art for which the Connecticut location is highly meaningful: places that inspired or appear in artistic or literary works such as the ponds on photographer Edward Steichen’s property, now Topstone Park, in Redding; gathering places where communities of artists and writers worked and exhibited such as Silvermine Art Guild in Fairfield County; public installations of significant artworks such as Calder’s Stegosaurus in Hartford and WPA murals in various public buildings around the state; exhibition sites associated with individual or institutional patrons such as Wadsworth Atheneum director Chick Austin’s house and the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, and the Slater Museum in Norwich; sites associated with fabricating art, publishing literary work, and education such as New Directions publishing house in Norfolk, Pomfret School, and the Norwich Free Academy; historic sites already recognized on the basis of earlier periods of significance which are now recognized for their role in 20th-century artistic or literary developments; and sites that particularly relate to the diversity of Connecticut’s artists and writers. Here we mention just a few of the dozens of sites in our ever-growing inventory. These sites are among those nominated to the State Register of Historic Places by the Connecticut Trust.

Hartford’s Affair with Modernism

Three important and controversial projects in Hartford span a period of 50 years and reflect the swings in the city’s love affair with modern art: the Wadsworth Atheneum’s Avery Memorial building, the Alfred E. Burr Mall south of the museum with its signature Alexander Calder Stegosaurus, and Carl Andre’s Stone Field sculpture just across Main Street from the museum entrance.

Modernism came to Hartford with Chick Austin in the 1920s, when he was named director of the Atheneum. Austin provoked and stimulated the local art world with exhibitions of modern art and the design of a new Bauhaus-inspired gallery, the 1934 Avery Memorial. The gallery’s international-style design became the backdrop for art of Picasso, Dali, and also American artists such as Milton Avery and Georgia O’Keefe. Opera and festive galas took place in the Avery Memorial’s theater and courtyard. But after almost 20 years, Hartford turned away from Austin’s cutting edge style and settled down for some years of a less adventurous direction, until the introduction of the MATRIX contemporary art gallery in the late 1970s.

By 1969 it was time for another fling with new-fangled art—the Alfred E. Burr Mall was designed to replace a short street between the Atheneum and the city’s Municipal Building. Modernist landscape architect Dan Kiley designed the space as a grid of marble rings, each with a tree centered within; Calder’s giant red steel Stegosaurus was recommended by Atheneum director Jim Elliott as the sculptural centerpiece. One of Calder’s few Connecticut public art installations and controversial at the time, “Stego” has become a beloved fixture in the Hartford scene. But the landscape has not survived intact. With the maturing of the trees and changing ideas about public space, the plaza design has been altered, indicating a movement away from the modernist design of the original.

By 1969 it was time for another fling with new-fangled art—the Alfred E. Burr Mall was designed to replace a short street between the Atheneum and the city’s Municipal Building. Modernist landscape architect Dan Kiley designed the space as a grid of marble rings, each with a tree centered within; Calder’s giant red steel Stegosaurus was recommended by Atheneum director Jim Elliott as the sculptural centerpiece. One of Calder’s few Connecticut public art installations and controversial at the time, “Stego” has become a beloved fixture in the Hartford scene. But the landscape has not survived intact. With the maturing of the trees and changing ideas about public space, the plaza design has been altered, indicating a movement away from the modernist design of the original.

Almost a decade later, 1977 another modernist public art piece was planned for a lot northwest of the Atheneum where Gold Street had been reshaped during 1960s redevelopment. The Hartford Foundation for Public Giving commissioned the work. The foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) each contributed to the $100,000 commission. Dozens of candidates were considered by a selection committee appointed by the foundation and the NEA. The committee chose Carl Andre’s proposal for Stone Field, an earth art piece composed of eight rows of Connecticut-sourced glacial boulders representative of the glacial deposition of this area. Here, Connecticut’s landscape and geological history were the source of inspiration for the artist, who creates art through the arrangement of raw objects without the traditional activities of carving or modeling. Like Calder’s Stegosaurus, Stone Field (one of Andre’s only public-art pieces) was ridiculed by some. But today it has come to be internationally recognized as the work of a major minimalist sculptor. Its placement adjacent to the Ancient Burial Ground invites reflection on the relationship of the rows of stones in both sites.

These three modernist works located at the center of Hartford remind us of the impulses in recent history, both to embrace modern art and to turn away from it. Chick Austin came to Hartford fresh from his education in a new profession of museum curation and shook up the cultural scene before being dismissed from his post in the early 1940s. His legacy remains in the Avery Memorial, the art he acquired for the museum, and in his unusual house on Scarborough Street. Calder settled in Roxbury, and his mobiles have become universally collected and displayed [See story, page xx.]. Andre, a native of Massachusetts who settled in New York, nevertheless tuned in to themes of mortality and geological time that make his Hartford piece truly site-specific, enjoyed for picnics and geology tours alike.

Gertrude Chandler Warner and the Putnam Boxcar Children Museum

In 2012, School Library Journal named Gertrude Chandler Warner’s The Boxcar Children series one of the “Top 100 Chapter Books” of all time. In Putnam, the Boxcar Children Museum, operated by the Aspinock Historical Society, keeps alive the memory of her beloved books. The museum, a recycled period boxcar, sits on a rail siding across the tracks from the historic Putnam Railroad Station (now on the National Register). Warner (1890-1979) was born in Putnam and grew up in a house across South Main Street from the railroad station. She dreamed of becoming an author and wrote stories for her grandfather, whose farm she enjoyed visiting. She published her first book, The House of Delight, in 1916.

In 1918, during the teacher shortage of World War I, Warner began teaching first grade at the then-new Israel Putnam School (now on the National Register) even though ill health had prevented her completing high school. She also began her first version of The Boxcar Children. She was inspired by her childhood memories of looking out her window and watching the trains passing and the cabooses with the trainmen living inside. She read the story to her classes and rewrote it repeatedly to refine and simplify the vocabulary. Many of her students were children of French Canadian mill workers and were learning English as a second language. The version still read today was published in 1942. Albert Whitman & Company published this first classic story and 18 more Alden-children adventures by Warner. (The series now includes more than 100 titles.) Warner was an early proponent of children’s books with plots that would be of interest to young readers and vocabulary that was age-appropriate—a nearly universal principle today. [For more on Connecticut’s children’s books, see “Once Upon a Time in Connecticut,” Fall 2014.]

For years, members of the Aspinock Historical Society had wanted to honor Warner and her books. They felt an actual boxcar would be the ideal vehicle for a small museum. The Connecticut Trolley Museum in East Windsor donated a circa-1929 wood-sided car, and the Providence and Worcester Railroad deeded part of their track right-of-way to the Town of Putnam. That allowed the town to grant a site to the historical society for the boxcar installation. The museum opened in 2004. The choice by the Aspinock Historical Society to re-purpose a period boxcar for the museum dramatizes the literature that is its subject matter while preserving an artifact of the area’s past railroad era.

Edward Steichen and Topstone Park

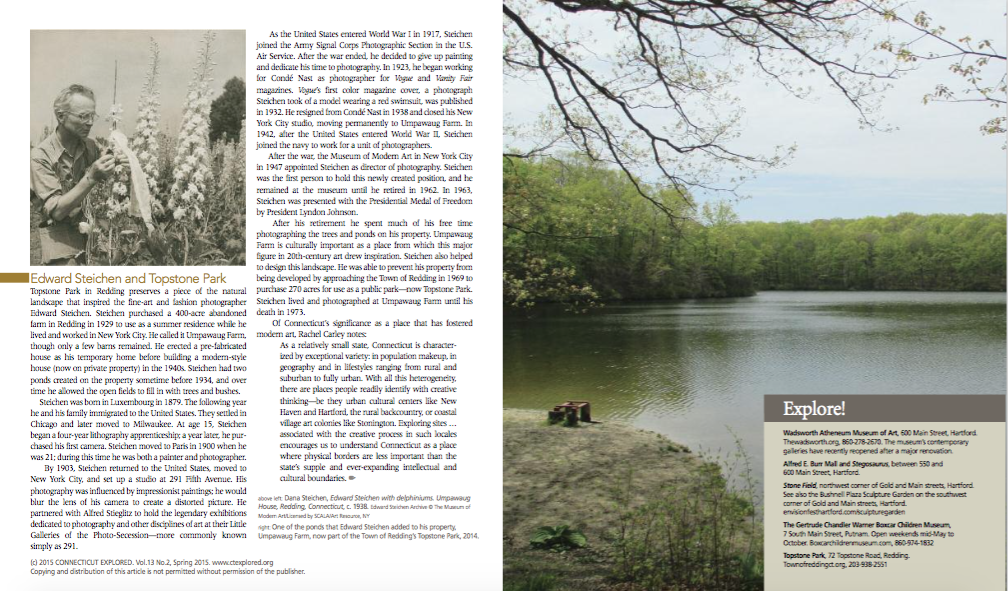

Topstone Park in Redding preserves a piece of the natural landscape that inspired the fine art and fashion photographer Edward Steichen. Steichen purchased a 400-acre property, an abandoned farm, in Redding in 1929 to use as a summer residence while he lived and worked in New York City. He called it Umpawaug Farm, though only a few barns remained. He erected a pre-fabricated house as his temporary home before building a modern-style house (now on private property) in the 1940s. Steichen had two ponds created on the property sometime before 1934, and over time he allowed the open fields to fill in with trees and bushes.

Steichen was born in Luxembourg in 1879. The following year he and his family immigrated to the United States. They settled in Chicago and later moved to Milwaukee. At age 15, Steichen began a four-year lithography apprenticeship; a year later, he purchased his first camera. Steichen moved to Paris in 1900 when he was 21; during this time he was both a painter and photographer.

Steichen was born in Luxembourg in 1879. The following year he and his family immigrated to the United States. They settled in Chicago and later moved to Milwaukee. At age 15, Steichen began a four-year lithography apprenticeship; a year later, he purchased his first camera. Steichen moved to Paris in 1900 when he was 21; during this time he was both a painter and photographer.

By 1903, Steichen returned to the United States, moved to New York City, and set up a studio at 291 Fifth Avenue. His photography was influenced by impressionist paintings; he would blur the lens of his camera to create a distorted picture. He partnered with Alfred Stieglitz to hold the legendary exhibitions dedicated to photography and other disciplines of art at their Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession—more commonly known simply as 291.

As the United States entered World War I in 1917, Steichen joined the Army Signal Corps Photographic Section in the U.S. Air Service. After the war ended, he decided to give up painting and dedicate his time to photography. In 1923, he began working for Condé Nast as photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair magazines. Vogue’s first color magazine cover, a photograph Steichen took of a model wearing a red swimsuit, was published in 1932. He resigned from Condé Nast in 1938 and closed his New York City studio, moving permanently to Umpawaug Farm. In 1942, after the United States entered World War II, Steichen joined the navy to work for a unit of photographers.

After the war, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1947 appointed Steichen as director of photography. Steichen was the first person to hold this newly created position, and he remained at the museum until he retired in 1962. In 1963, Steichen was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Lyndon Johnson.

Steichen was inspired by the nature surrounding him, and after his retirement he spent much of his free time photographing the trees and ponds on his property. Umpawaug Farm is a site that is culturally significant as a place from which this major figure in 20th-century art drew inspiration. Steichen also helped to design this landscape. He was able to prevent his property from being developed by approaching the Town of Redding in 1969 to purchase 270 acres for use as a public park—now Topstone Park. Steichen lived and photographed at Umpawaug Farm until his death in 1973.

Of Connecticut’s significance as a place that has fostered modern art, Rachel Carley noted:

As a relatively small state, Connecticut is characterized by exceptional variety: in population makeup, in geography and in lifestyles ranging from rural and suburban to fully urban. With all this heterogeneity, there are places people readily identify with creative thinking—be they urban cultural centers like New Haven and Hartford, the rural backcountry, or coastal village art colonies like Stonington. Exploring sites … associated with the creative process in such locales encourages us to understand Connecticut as a place where physical borders are less important than the state’s supple and ever-expanding intellectual and cultural boundaries.

Kristen Nietering and Charlotte Hitchcock work at the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation on the project Creative Places: Modern Arts and Letters in Twentieth-century Connecticut.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s Art History and Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS pages.

Preservation Connecticut’s Creating Places WEBSITE, ConnecticutCreativePlaces.org

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 600 Main Street, Hartford. Thewadsworth.org, 860-278-2670. The museum’s contemporary galleries are reopened after a major renovation.

Alfred E. Burr Mall and Stegosaurus, between 550 and 600 Main Street, Hartford.

Stone Field, northwest corner of Gold and Main streets, Hartford. See also the Bushnell Plaza Sculpture Garden on the southwest corner of Gold and Main streets, Hartford. envisionfesthartford.com/sculpturegarden

The Gertrude Chandler Warner Boxcar Children Museum, South Main Street near Union Square, Putnam. Open weekends mid-May to October. Boxcarchildrenmuseum.com

Topstone Park, 72 Topstone Road, Redding. Townofreddingct.org, 203-938-2551