by Thomas M. Truxes

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The quarter century before the outbreak of the American Revolution was the Golden Age of Smuggling in Connecticut. Prosperity there and elsewhere in colonial America—where recurring economic hardship was a fact of life—depended on the vitality of markets and the free flow of goods. Tariffs and other forms of trade regulation required under British law stifled the flow of commerce and reduced real incomes.

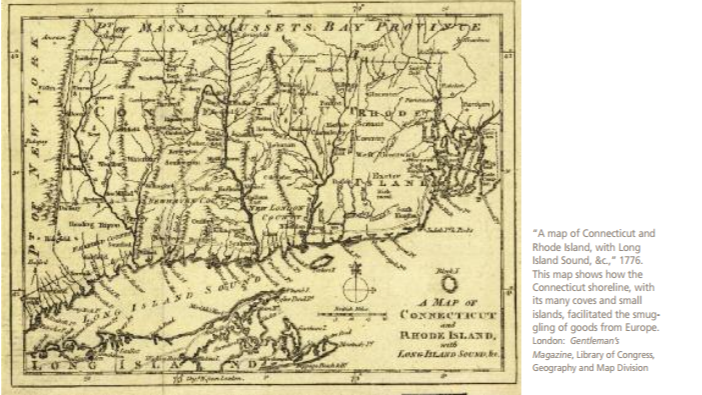

Unlike its neighbors—New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island—Connecticut did not have a well-developed transatlantic trade of its own. Merchants in New London, New Haven, and other Connecticut ports did a thriving business in the West Indies and occasionally became involved in slaving voyages to West Africa. Only rarely did they send their own vessels to the British Isles or to the ports of continental Europe, preferring instead to work in partnership with trading houses in New York, Newport, and Boston. Even so, Connecticut figured prominently in the transatlantic trade of British America. Geography conspired with the colony’s political and legal structure to give Connecticut a crucial role in the movement of goods from the European continent to consumers in America. Most cargoes originated in the Dutch ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, the German free-port of Hamburg, or the port of Copenhagen in the Kingdom of Denmark. Such trade defied the British Parliament’s Acts of Trade and Navigation requiring that all European goods bound for colonial America be transshipped through ports in Great Britain.

Unlike its neighbors—New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island—Connecticut did not have a well-developed transatlantic trade of its own. Merchants in New London, New Haven, and other Connecticut ports did a thriving business in the West Indies and occasionally became involved in slaving voyages to West Africa. Only rarely did they send their own vessels to the British Isles or to the ports of continental Europe, preferring instead to work in partnership with trading houses in New York, Newport, and Boston. Even so, Connecticut figured prominently in the transatlantic trade of British America. Geography conspired with the colony’s political and legal structure to give Connecticut a crucial role in the movement of goods from the European continent to consumers in America. Most cargoes originated in the Dutch ports of Amsterdam and Rotterdam, the German free-port of Hamburg, or the port of Copenhagen in the Kingdom of Denmark. Such trade defied the British Parliament’s Acts of Trade and Navigation requiring that all European goods bound for colonial America be transshipped through ports in Great Britain.

In “the Dutch trade,” the popular name for this illegal activity, Connecticut was a willing and able facilitator. Merchants outside Connecticut, a royal official complained in 1757, initiated and financed smuggling voyages, “sending their Vessels to the Ports of Connecticut, from whence it is not very difficult to introduce their goods through the sound to New York, and even to Philadelphia.” It was a large and profitable business. “There is no trade here that brings so much gain as this contraband trade,” wrote a New York City merchant to a friend in Ireland. The thriving Dutch trade was a barometer of economic expansion in British America on the eve of the Revolution.

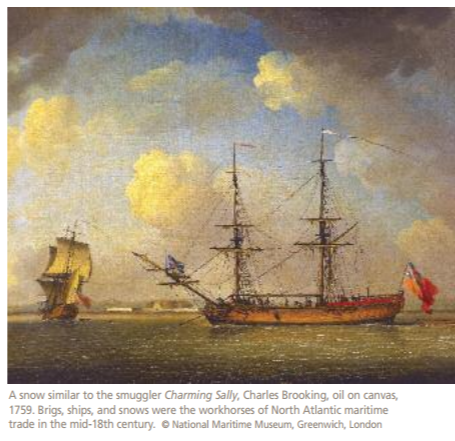

American trading vessels—many of them bound for Connecticut—were a common sight in the crowded harbors of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Hamburg, and Copenhagen in the decades before the Revolution. Through documents preserved in the British National Archives, it is possible to reconstruct the voyage of one of these ships, the Charming Sally of New York, on a journey from Amsterdam to New York with a detour through Long Island Sound. Like many other merchant vessels, the Charming Sally conducted its clandestine trade through intermediaries in Connecticut. Merchants and ship captains involved in this activity were conscious of the risks posed by both patrolling British warships on the high seas and over-zealous customs officers in colonial ports.

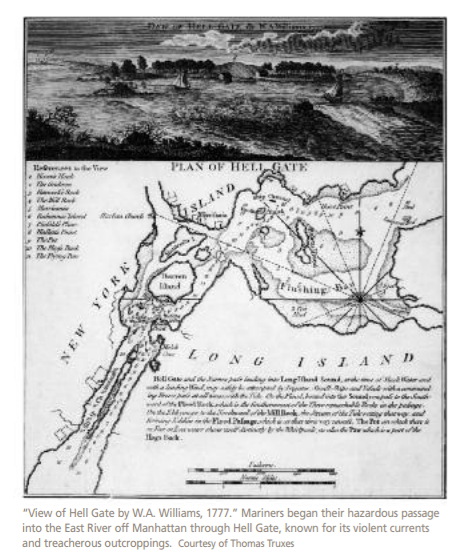

On its homeward journey in the late summer of 1756, Charming Sally followed a “north about” route, sailing through cold waters north of Scotland into the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and down the coast of New England. “At Sun Sett,” notes the ship’s logbook on September 29, “see the Land & Reckon Block Island.” The following morning, Captain Israel Munds took his vessel through “the Race,” the treacherous tidal currents at the entry point to Long Island Sound, then “steered over for New London harbor.”

“At 1 O’Clock [in the]afternoon Came to an Anchor, Hoysted our Boat out & our Captain went up to Town.” In New London, Captain Munds worked out arrangements with Joseph Chew, a merchant and customhouse officer, for offloading cargo at Fishers Island and at drop-off points along the Connecticut shore. In the 1750s and 1760s, Chew represented as many as a dozen trading houses in New York City, supplying incoming captains with false documents and coordinating the movement of their vessels.

With instructions in hand, Captain Munds and Charming Sally “weighed and run over to Fishers Island,” where he left some of his goods in storage and transferred others to coasting vessels from as far away as Philadelphia. Fishers Island, about two miles off the Connecticut coast, was a busy distribution point in the Dutch trade. During Munds’s 16-day visit in October 1756, five ships departed for New York, one for Boston, and another for Newport under the command of a Rhode Island shipmaster active in New York’s Dutch trade.

Off-loading complete and the wind rising, Charming Sally “turned out in the Sound then made all sail we could set,” according to the captain’s log. Soon, Munds’s trading vessel was running “abreast of Connecticut” along a coast replete with rivers, creeks, and inlets, communicating with prefixed drop-off points by signal flags and lanterns to “unload without the inspection of any officer,” according to a British report on Connecticut’s custom service. From aboard the Charming Sally, goods were dropped off at Falkner Island, “to the Eastward of New Haven,” and in the neighborhood of Milford.

The final leg took Charming Sally past Sands Point, Execution Rock, and the Stepping Stones to “Frogs Point”—the name Captain Munds gave to Throgs Neck— where, on October 20, 1756, Charming Sally dropped anchor while one of its owners, John Laurence of Queen Street in New York, came up from the city under cover of darkness to inspect his ship and the remaining cargo. With most of the cargo safely stowed on Fishers Island and in sheds and barns along the Connecticut coast, Captain Israel Munds began the hazardous passage into the East River and through Hell Gate, feared for its violent currents and treacherous outcroppings.

Great Britain’s imperial trading system was governed by a complex (and sometimes contradictory) set of rules. The Acts of Trade and Navigation—the first of them dating from 1660—required that certain colonial articles, such as sugar and tobacco, be shipped exclusively from ports within the empire and that the shippers pay the various duties prescribed by law. In addition, the navigation acts mandated that westbound cargoes be sent from ports in Great Britain. Shipping tea, spices, fine fabrics, and other goods to British America from places in continental Europe (at peace with Great Britain) was perfectly legal, so long as the ship called at a port in Great Britain, off-loaded then reloaded the cargo, and paid the required duties, fees, and handling charges before continuing the voyage.

Smuggling, broadly speaking, was trade that circumvented the Acts of Trade and Navigation. It thrived in New England and the Middle Colonies, where merchants were “accustomed to despise all laws of trade,” according to a letter in the archives of Windsor Castle from a New York politician to Lord Halifax.

Smuggling, broadly speaking, was trade that circumvented the Acts of Trade and Navigation. It thrived in New England and the Middle Colonies, where merchants were “accustomed to despise all laws of trade,” according to a letter in the archives of Windsor Castle from a New York politician to Lord Halifax.

Smuggling in British America took a variety of forms. In the mid-1750s, for example, American-bound ships routinely visited the Isle of Man to load contraband tea, India goods, and spirits after clearing customs in Liverpool. There was also a steady flow into the colonies of “foreign” (code for French) sugar and sugar products obtained through Dutch, Danish, and Spanish intermediaries in the West Indies or directly from the French themselves.

Of all smuggling activities, the Dutch trade was the most sophisticated and best integrated into the fastdeveloping consumer culture of New England and the Middle Colonies. The Dutch trade was, at its core, the shipping of goods from the European mainland to North America without fulfilling the Crown’s requirement that the merchant vessel stop at a port in Great Britain and enter its goods. By shipping directly, a merchant stood to save the cost of off-loading and reloading his goods and to avoid import and export taxes. He was then able to undercut his competition by selling his smuggled goods at a lower price.

Connecticut’s facilitating role in the Dutch trade was encouraged by geography, an under-funded customs service, politics, and an anomaly in the colony’s legal structure. The first of these, geography, made the Connecticut shoreline—with its many creeks, rivers, inlets, and small islands—a smuggler’s paradise. Added to this is the fact that New London was Connecticut’s single legal port of entry until 1757 when a second customs house was added at New Haven. The severely understaffed customs service lacked the resources to do much more than keep up with routine transactions.

The structure of government in Connecticut likewise contributed to an environment accommodating to illicit trade. The people of Connecticut, wrote the Board of Trade to the Privy Council in 1759, “under pretence of the Power granted to them by their Charter, assume to themselves an absolute Government, independent, not only of the Sovereign Government of the Crown, but of the Legislature of the Mother Country; For they not only do not transmit any of their Acts and Proceedings, either judicial or legislative, for the Royal Approbation, but likewise do not conform to the Laws of Trade.”

Connecticut governors were elected officials, not political appointees serving at the sufferance of London, as was the case in all of the other colonies except Rhode Island. As public officials dependent upon local interests, Connecticut governors had little to gain by angering constituents benefiting from smuggling operations that provided employment for merchants, mariners, and others along the Connecticut shoreline. Finally, the colony lacked an effective means of customs enforcement. The vice–admiralty court in Connecticut rarely met, and nearly all cases related to customs issues were heard in local courts before Connecticut judges and Connecticut juries.

The goods that illicitly entered New York, Philadelphia, and elsewhere via Long Island Sound fit comfortably into the flow of North Atlantic commerce. Merchants in Amsterdam and Rotterdam did a large business in Bohea tea, a Chinese black tea, which undercut the equivalent product from the British East India Company. The Dutch ports and Hamburg were also convenient sources for oznabrig, a cheap German linen that was popular throughout British America. Russian duck, ideal as sailcloth, was sent from these places but could be had even more favorably through Copenhagen. The Dutch trade was likewise a source of calico, muslin, and taffeta from India, along with more prosaic articles such as paper and glazed tiles.

Demand for such articles was driven by a rapidly expanding population and rising incomes in colonial America and by the far-reaching “consumer revolution” taking hold on both sides of the Atlantic. Workshops in the British Isles and continental Europe struggled to keep up with demand. By the middle of the 18th century, efficient and orderly channels of distribution were moving goods imported via the Dutch trade from their shadowy points of entry in Connecticut into shopkeepers’ inventories as far away as Pennsylvania.

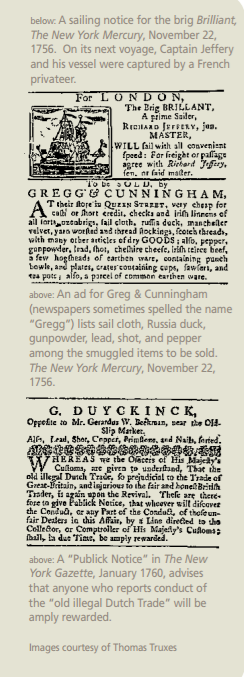

Merchants in New York sometimes dispatched fast-sailing sloops into the Sound to intercept incoming vessels from Europe in order to pass along instructions and spirit valuable cargoes into the city. Captain Richard Jeffery, master of the brig Brilliant, another of the incoming vessels from Amsterdam in the autumn of 1756, was ordered to rendezvous with a sloop from the city before depositing the bulk of his cargo at Stamford. “You may send us directly down about twenty cases of tea and . . . as much oznabrig as you can stow under the deck,” he was told by the brig’s owners. “And if you can spare the mate or a trusty hand, send one along.” Many ships came up to the city in ballast (i.e., without cargoes), after which the goods left behind were transferred from hiding places in Connecticut to warehouses in New York.

Agents in New Haven, Milford, Fairfield, Norwalk, and Stamford facilitated the Dutch trade. The most important of these was John Lloyd of Stamford, Joseph Chew’s counterpart at the western end of Long Island Sound. Captain Jeffery of the Brilliant was instructed to anchor in the middle of the Sound and send a mate to confer with Lloyd, “whose direction you are desired to follow in the delivery of the cargo. . . . Mr. Lloyd will provide you a clearance from Fairfield in ballast.” Fast-moving sloops such as Lloyd’s 18-ton Weymouth and 15-ton Stamford busied themselves ferrying cargoes from Stamford and Fairfield to wharves along the length of the East River.

From the holds of ocean-going vessels such as the Brilliant and Charming Sally—and coasting sloops such as the Weymouth and Stamford—smuggled goods found their way to shopkeepers’ shelves throughout the region. John Fell, a merchant on King Street in New York, told a committee of the British House of Commons in the early 1750s that he had seen a piece of Dutch linen in a shop at New York marked cheaper at retail than what he could purchase the equivalent British linen for at wholesale. Although Fell was unable to estimate “what quantity of linen goods are smuggled into New York,” he remarked that it was common practice for them to be “publicly landed, though not entered” at the customhouse. As long as officials in Connecticut and New York looked the other way—for a price—the Dutch trade thrived.

Before the mid-1750s, London paid little attention to the smuggling of fabrics, chinaware, tea, and other consumer goods through Connecticut. During the 1730s and 1740s, the British ministry followed a broad and tolerant policy of “benign neglect” with respect to the colonial economy. Sporadic efforts to crack down on smuggling in America were half-hearted. Far more important from London’s perspective was protecting Great Britain’s stake in the West Indian sugar trade, the nation’s most lucrative branch of Atlantic commerce. There were, as well, serious attempts to disrupt the running of American tobacco and rum into Great Britain and Ireland, motivated mainly by the determination of the customs service to collect duties owing to the Crown.

Before the mid-1750s, London paid little attention to the smuggling of fabrics, chinaware, tea, and other consumer goods through Connecticut. During the 1730s and 1740s, the British ministry followed a broad and tolerant policy of “benign neglect” with respect to the colonial economy. Sporadic efforts to crack down on smuggling in America were half-hearted. Far more important from London’s perspective was protecting Great Britain’s stake in the West Indian sugar trade, the nation’s most lucrative branch of Atlantic commerce. There were, as well, serious attempts to disrupt the running of American tobacco and rum into Great Britain and Ireland, motivated mainly by the determination of the customs service to collect duties owing to the Crown.

The most vigorous push to shut down the Dutch trade in Connecticut came in 1756 after the formal opening of the Seven Years’ War (the conflict better known in the United States as the French and Indian War). British military planners were convinced that smuggling weakened the wartime economy and played into the hands of the French enemy. The seizures began early in May 1756 in New York City—where they “made great Noise,” according to one customs official—and were in full force in Connecticut by summer. “I acquainted Governor Fitch [of Connecticut]with some informations I had obtained,” reported Sir Charles Hardy, governor of New York, “and requested him to direct the Custom house Officers of his Colony to do their duty.” By the autumn, however, the Dutch trade had resumed its course. But it was no longer so brazen and visible.

The period between 1763 and the outbreak of the Revolution saw a dramatic shift in British attitudes toward smuggling in America. In April 1763, Parliament passed a harsh new law that signaled an end to the peacetime tolerance of illicit trade. The Customs Enforcement Act of 1763 deputized officers of the Royal Navy stationed in America to serve as customs agents. Following passage of the act, the Admiralty stationed 21 British warships—half of them nimble sloops of war—along the coast of North America to interdict vessels carrying contraband cargoes.

In the dozen years between 1763 and the outbreak of fighting at Lexington and Concord, Long Island Sound and the Connecticut shoreline continued to serve as an entry point for smuggled goods from Europe, with Connecticut merchants and mariners continuing to play a facilitating role. But positions on both sides hardened. Officials in London increasingly saw Americans as lawless and recalcitrant children in need of harsh discipline. And the people of Connecticut—accustomed to selfgovernment and a high degree of independence—saw British interference in their fragile maritime economy as arbitrary and tyrannical. Resentments festered on both sides and became part of the backdrop of the American Revolution.

Explore!

Read more MARITIME history stories on our TOPICS page.