(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

For the first two bloody years of the American Civil War the subject of allowing Black men to enlist was heavily debated. Opponents argued that Blacks would not make good fighting men and that they lacked the military skills and fortitude to effectively participate in the war. The argument ignored the fact that Black men had fought in and made important contributions to every previous American war, most notably the Revolutionary war.

In January 1863, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, a document that freed slaves in the border states and authorized the enlistment of Black soldiers. On May 22, 1863, the United States Department of War issued General Order No. 143 establishing the Bureau of Colored Troops. Connecticut did not move as quickly as other New England states such as Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Nonetheless, on November 13 at a special session of the General Assembly, Col. Dexter R. Wright, seconded by Col. Benjamin S. Pardee, both from New Haven, proposed a bill authorizing Governor William A. Buckingham to organize regiments of “colored” infantry. Connecticut Democrats denounced the bill in unmeasured terms, arguing it would let loose upon the helpless South “a horde of African barbarians.” They predicted Black cowardice, disgrace, and ruin as the result of the experiment.

Governor Buckingham moved swiftly, though, authorizing the bill on November 23 and calling for volunteers to make up the 29th Regiment Colored Volunteers. Despite the fact that many Black laborers earned wages that were higher than army pay and enlistment bounties, the response was immediate and enthusiastic. By January 1864 more than 1,200 men flocked to the 29th and more than 400 joined an additional colored regiment, the 30th (and, eventually, the 31st), Regiment United States Colored Infantry. Civil War historian William A. Gladstone in United States Colored Troops 1863-1867 (Thomas Publications, 1990) indicates that 1,764 men of color served Connecticut during the Civil War between 1863 and 1867. The level of Black participation in Connecticut regiments was astounding considering that the 1860 census revealed only 8,726 Black people living in the state; of them only 2,206 were men between the ages of 15 and 50 (the most likely ages for service). This meant that some 78 percent of eligible black men enlisted. Just over 15 percent of these men died as a result of the war.

The men were offered an enlistment bounty of $600 and the same pay and uniforms as white soldiers. The 29th and 30th regiments were encamped near Fair Haven, and by the end of January, as the regiments’ officers—all of them white—were chosen, daily drills and a system of rigid inspections were established. On January 29, 1864, the soldiers of the 29th and 30th were addressed by the famed Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who told them (according to William A. Croffut and John M. Morris, The Military & Civil History of Connecticut During The War of 1861-65 (Boston: Ledyard Bill, 1868),

You are pioneers of the liberty of your race. With the United States cap on your head, the United States eagle on your belt, the United States musket on your shoulder, not all the powers of darkness can prevent you from becoming American citizens. And not for yourselves alone are you marshaled—you are pioneers—on you depends the destiny of four millions of the colored race in this country. If you rise and flourish, we shall rise and flourish. If you win freedom and citizenship, we shall share your freedom and citizenship.

But these men already understood this. Ministers Alexander Newton in Out of the Briars, An Autobiography and Sketch of the Twenty-ninth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers (1910) and Isaac Hill in A Sketch of the 29th Regiment of Connecticut Color Troops (1867) both reflected on their time in the 29th. Newton, who was an abolitionist before the war and active in the Underground Railroad, wrote, “Although free born, I was born under the curse of slavery, surrounded by the thorns and briars of prejudice, hatred, persecution and the suffering incident to this fearful regime.” In going to war, he suggested, he was “doing what he could on the battlefield to liberate his race.”

On March 8, the regiment was mustered into service and soon thereafter received as its commanders Colonel William B. Wooster of Derby, Lt. Colonel Henry C. Ward of Hartford, and Major David Torrance of Greenville (part of Norwich). On March 19, after receiving a United States flag from a group of Black women from New Haven, the regiment assembled on the New Haven Green. As they paraded toward the waterfront for their departure, well-wishers showered them with flowers. The men embarked on the Warrior for Annapolis, Maryland.

On March 8, the regiment was mustered into service and soon thereafter received as its commanders Colonel William B. Wooster of Derby, Lt. Colonel Henry C. Ward of Hartford, and Major David Torrance of Greenville (part of Norwich). On March 19, after receiving a United States flag from a group of Black women from New Haven, the regiment assembled on the New Haven Green. As they paraded toward the waterfront for their departure, well-wishers showered them with flowers. The men embarked on the Warrior for Annapolis, Maryland.

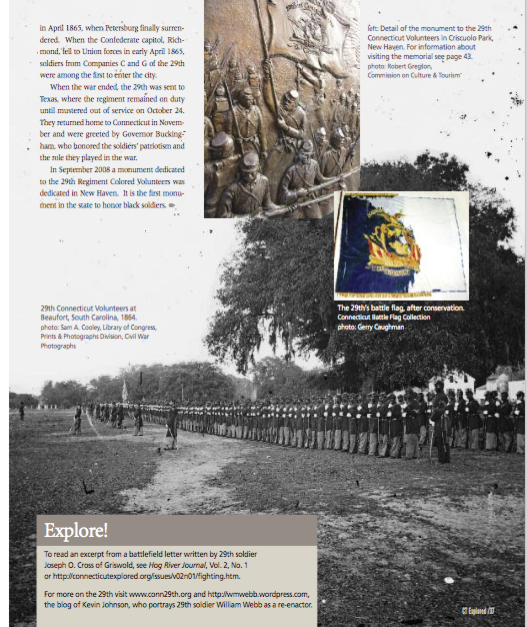

The 29th was ultimately transported to Beaufort, South Carolina, where its members performed guard and picket duty for four months. In August, they were brought to the siege lines of Virginia. The 30th served on guard duty in Virginia during the first half of June, then entered the Petersburg trenches and participated in the famous Crater attack on July 30, when the Union military attempted to dig and explode a tunnel directly under Confederate lines. The 30th suffered 82 casualties in a slaughter by rebel forces. The 29th and 30th regiments, along with the rest of the Army of the Potomac, moved around the city, fighting in a host of battles, from Bermuda Hundred to the Battle of Fair Oaks, before achieving success in April 1865, when Petersburg finally surrendered. When the Confederate capitol, Richmond, fell to Union forces in early April 1865, soldiers from Companies C and G of the 29th were among the first to enter the city.

When the war ended, the 29th was sent to Texas, where the regiment remained on duty until mustered out of service on October 24. They returned home to Connecticut in November and were greeted by Governor Buckingham, who honored the soldiers’ patriotism and the role they played in the war.

In September 2008 a monument dedicated to the 29th Regiment Colored Volunteers was dedicated in New Haven. It is the first monument in the state to honor Black soldiers.

Charles (Ben) Hawley is a Civil War re-enactor with the 54th Mass in Washington, D.C. and a 29th Regiment Descendant.

Explore!

To read an excerpt from a battlefield letter written by 29th Regimental soldier Joseph O. Cross of Griswold, see Hog River Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1.

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War in the Spring 2011 and Winter 2012/2013 (150th Anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation) issues, and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.

Read more about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.