By Dawn C. Adiletta

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2017

SUBSCRIBE/Buy the Issue!

“Monday I gathered hops,” wrote Thomas Minor of Stonington in September 1661. Connecticut farmers cultivated hops from colonial times through the end of the 1800s. Now, after a break of more than a century, Connecticut farmers from Sharon to Salem once again grow hops for local commercial and home brewers.

Hops (homulus lupulus) grow wild in North America, but Massachusetts colonists domesticated them by 1628. It’s not surprising that hops were cultivated so quickly. As W.J. Rohrbach outlined in The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (Oxford University Press, 1981), early Europeans imported their concerns about unhygienic drinking water and made fermented beer and hard cider dietary basics. Hops’ value as a natural preservative also made them an important export commodity.

Since one vine, or bine, provides enough hops to preserve 10 to 50 gallons of beer, creating a surplus was easy. “[S]ent Hopps to NY,” New London’s Joshua Hempsted (of Connecticut Landmarks’s Hempsted Houses) wrote in 1746, adding he received more than 31 pounds sterling for 29 pounds of hops—a considerable amount.

References to hops pepper early Connecticut diaries and ledgers. Between them, Thomas Minor and his son Manassah recorded cutting hop poles and weeding hops for close to 60 years. Hempsted regularly mentioned “poling my hop yard” and “pulling hopps” for two decades. In West Hartford, Noah Webster’s parents raised hops during the 1760s.

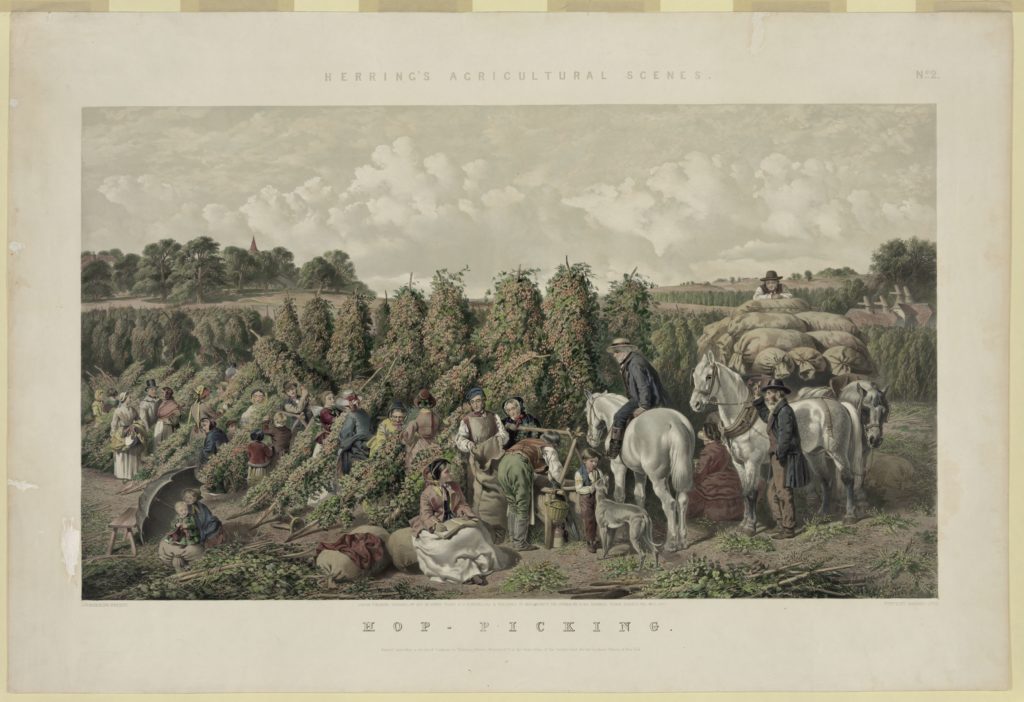

In the wild, hops wind up trees and over bushes, but to maximize yield, colonial farmers planted rows of female hops in low mounds about eight feet apart to encourage air circulation and discourage mildew. A 12-to-16-foot pole was erected near each plant, and the young bine was trained to climb it. When the cone-like flowers bloomed in mid-September, bines were clipped at their bases, the poles were pulled from the ground, and bine and pole were placed horizontally over a large wooden box, or crib, to collect the hand-picked flowers. The flowers must be used quickly or dried over a low fire in a hop-house, or oast, to prevent mildew. Most were dried and exported.

In the early 1800s, as German immigration to the United States increased, lagers gained popularity and more commercial breweries opened, including several in Connecticut. Hoping to profit from brewers’ demands, farmers turned to the do-it-yourself guides of their day, monthly journals such as New England Farmer and American Farmer. “Every farmer should grow their own hops,” advocated The Genesee Farmer in 1837.

The September 1823 edition of American Farmer reported an annual U.S. hop harvest of a million pounds, mostly from New England, and bragged of New England hops’ good international reputation. By the early 1800s most hops came from Vermont, but by the 1830s New York dominated U.S. hop production and would do so until the 20th century. In 1850 Connecticut produced just 500 pounds of hops to Vermont’s 288 thousand pounds, while New York generated an excess of 2.5 million pounds. As Adam Krakowski wrote in A Bitter Past: Hop Farming in 19th-Century Vermont, (Vermont History Vol. 82, No. 2, 2014), richer soils, better weather, and better market proximity encouraged large hopyards in Vermont and New York. Most Connecticut farmers harvested less than 10 pounds a year. The American Farmer estimated 800 pounds of hop flowers per acre, indicating Connecticut farmers grew only a few bines at a time. Even Thomas Grosvenor of Pomfret, who harvested 30 pounds in 1850, barely required a 1/16th-acre hopyard. Tiny hopyards bloomed across the state, but there was rarely more than one per town.

In 1854, Connecticut’s prohibition law closed taverns and public houses. Unlike under the 1920 national law, however, breweries and distilleries remained open, keeping the demand for and the prices of hops high. Output nearly doubled in 1860, including in Connecticut, causing over-production. “There has been more money lost in hops the last year than would richly endow an agricultural college,” lamented the January 1869 New England Farmer. The realities of fluctuating markets and flourishing western hopyards finally induced local hop growers to cut their losses. Connecticut farmers produced few hops by the time the prohibition law was rescinded in 1872, and reported none in 1890.

National prohibition in the 1920s eliminated the domestic hop market, although hops remained an important export crop. By prohibition’s repeal in 1933, western hopyards dwarfed even New York’s. Today half the world’s hops grow in the Pacific Northwest.

The resurgent interest in local brews has re-incentivized Connecticut hop growers, who combine old and new techniques. Iconic poles support overhead wire trellises, bines climb hemp twines, and instead of handpicking, harvesters cut twine and bine together and mechanically strip the blossoms. Hybrid varietals produce individual tastes and greater yields. But just like Thomas Minor 350 years ago, modern farmers still battle weather and a fluctuating market to produce local goods.

Dawn C. Adiletta is a historic consultant and writer active in farmland preservation.

Explore!

Read about the brewery strike in 1906 in Hartford: Hartford’s Union Brew

Listen to our podcast about hops, beer, and Hartford’s brewery strike, and more! Grating the Nutmeg Episode 32.

More stories from the Summer 2017 issue