By Brent S. Bette

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Visible evidence of the contributions railroads made to the development of the nation is becoming increasingly hard to find. Stations have been torn down, tracks removed or converted to trails for walking and biking, and the romantic notion of traveling by rail is but a memory. Once-ubiquitous corporations such as the Pullman Car & Manufacturing Company, which once enjoyed a status similar to that of Apple or Google, remain familiar only in the vernacular of history. For nearly 50 years, the Railroad Museum of New England (RMNE), along with several other organizations in the state (see Explore! below), has been on a mission to collect and preserve artifacts representing the impact railroads have had on the development of Connecticut and the region.

The Railroad Museum of New England, based in Thomaston, Connecticut, has an extensive collection ranging in size from conductor’s uniform buttons to a 210-ton steam locomotive that traversed Eastern Canada. One of RMNE’s most significant and visible accomplishments has been the restoration of its 1881 station in Thomaston. The museum’s collection includes 73 railroad cars (also called rolling stock) including a 1904 wooden dining car from the once-dominant New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad. The museum maintains an operational demonstration railroad, which extends 19 miles from Waterbury to Torrington.

The sheer size of many railroad artifacts makes their preservation daunting. Railroads originally employed tens of thousands of specialized workers to perform tasks now undertaken by the museum’s all-volunteer workforce. And with size comes cost. Restoring a steam locomotive to working condition, which the museum aspires to do, can cost more than a million dollars.

People involved in rail preservation covet the rare find. Those seeking railroad-related artifacts face a particular challenge because locomotives and passenger cars typically were used until they wore out. While this is typical of most industrial products, realities of scale dictated that obsolete rolling stock would not be resold for any purpose other than scrap. Individual collectors have had difficulty rationalizing the purchase, let alone movement, of anything larger than a caboose or trolley for use as a backyard workshop or chicken coop. Thus much of our railroad heritage has been lost.

Two of the larger objects in the museum’s collection illustrate the extremes of railroad travelers’ experiences. The museum’s 1930 Pullman car, “Stag Hound,” represents the luxurious way in which the region’s wealthy traveled in the early 20th century. No expense was spared to ensure that accommodations reflected the expectations of the nation’s most affluent families. The second example, the 1881 Thomaston station, tells a much different story. Representative of the typical country station, the building was the epicenter of the town and represented the gateway to the outside world. But it was a working building. News, passengers, and raw materials, all crucial for the survival of the town, passed through its doors. Both of these artifacts are critical to providing a well-rounded understanding of the profound impact the railroads had on almost every facet of life in New England from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century.

For the first half of the 20th century, the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, commonly referred to simply as the New Haven, was a leading economic force in southern New England. A conglomeration of smaller railroads, the company began to take shape in 1872 when the New Haven and Hartford Railroad and the New York and New Haven Railroad were consolidated. During the next 50 years, the company, aimed to monopolize rail travel in the region. Headquartered in New Haven, the operation had a relatively small geographic footprint compared to other eastern railroads. But what the system lacked in mileage, it made up for in density. Serving some of the most heavily industrialized cities in the nation (including the three listed in the company’s full name), the rails of the New Haven represented the arteries of commerce. Passenger ridership also was sizeable, at times contributing half of the company’s yearly gross earnings. The other half was generated by shipping freight produced by the industrial centers throughout the region.

While ordinary citizens rode in standard coach class, the wealthy of Boston and New York demanded luxury, and the ever-enterprising New Haven was happy to oblige, offering plush accommodations and a premium ticket fare. The fast-paced financial world also demanded speed. With this in mind, the company launched the upscale New York-to-Boston Merchants Limited in December 1903. Naming certain trains and their routes (think the Orient Express) was a practice on nearly every railroad in America and Europe. While all train trips were assigned a number (much like flights today), trains (and their routes) catering to the upper class were assigned names too. Hence, one would hear, “We took the Merchant’s down from Boston yesterday.” The Merchants Limited trains left New York’s Grand Central Terminal and Boston’s South Station at 5 p.m. daily, making the journey to the end of the line in an impressive (for the time) five hours.

The Merchants Limited initially featured “palace cars” made largely of wood, but greater speeds and an embarrassing and deadly string of wrecks in 1911, 1913, and 1916 spurred an upgrade to state-of-the-art steel construction. Manufactured by the Pullman Company, each car was outfitted with the best accommodations the company had to offer, and the New Haven ordered brand-new equipment in 1926, 1927, and 1929—a nearly unprecedented rate of improvement within the industry but in keeping with the booming economy of the day. The Merchants Limited arrived in New York and Boston at 10 p.m., which was ideal for travelers attending an early business meeting the next day. But it was not conducive to enjoying the nightlife each city had to offer. By the mid-1920s, the demand for an earlier train prompted the New Haven to offer the same service but with an arrival time of 5 p.m. The railroad opted to order new rolling stock from Pullman, choosing what would become the iconic heavyweight “Pullman cars” that would later captivate railroad preservationists. The New Haven decided that employees, rather than executives, should be given the honor of naming the new train. On January 8, 1930, The New York Times reported, “John Coolidge Picked Name for New Train; ‘Yankee Clipper’ Begins Service April 1.”

The Merchants Limited arrived in New York and Boston at 10 p.m., which was ideal for travelers attending an early business meeting the next day. But it was not conducive to enjoying the nightlife each city had to offer. By the mid-1920s, the demand for an earlier train prompted the New Haven to offer the same service but with an arrival time of 5 p.m. The railroad opted to order new rolling stock from Pullman, choosing what would become the iconic heavyweight “Pullman cars” that would later captivate railroad preservationists. The New Haven decided that employees, rather than executives, should be given the honor of naming the new train. On January 8, 1930, The New York Times reported, “John Coolidge Picked Name for New Train; ‘Yankee Clipper’ Begins Service April 1.”

The economic constraints imposed by the Great Depression and World War II prevented replacement of the Yankee Clipper’s Pullman cars until 1947. Many of the New Haven’s old Pullman cars suffered the indignity of being converted to ordinary coaches. “Stag Hound,” in what might have been a lucky stroke leading to its eventual preservation, was chosen by the South Shore Club, an exclusive group of Boston-area businessmen who paid a premium fare to have their own reserved car for the daily commute from places such as Plymouth to South Station. (Similar elite social institutions had come into existence on the New York end of the railroad as early as the 1890s.)

Passenger service on the New Haven’s Old Colony division ended in 1959, and “Stag Hound” seemed destined for the scrap heap. This key piece of New England railroad history would have been lost but for the intervention of Jim Bradley, a postal worker from Stonington, Connecticut. Through his efforts in the early 1960s “Stag Hound” and five other historic passenger cars from the New Haven Railroad were spared.

Bradley was a grandson of Edward E. Bradley, one of the three founders of Mystic Seaport, so historic preservation ran in his blood. He was also related to “Conductor Bradley,” a heroic victim of an 1873 Connecticut train wreck who was the subject of a once-famous poem by New England poet John Greenleaf Whittier. Jim Bradley’s property in Stonington overlooked the main line of the New Haven Railroad, and he regularly saw the condemned Pullmans rolling by on their way to the scrappers’ yards. He contacted the railroad in 1962 to ask about purchasing one or two of the cars.

One year into its final bankruptcy, the New Haven Railroad was receptive to his inquiry. Bradley used his life savings and a bank loan to purchase “Stag Hound.” He hired house movers to haul the train car from Mystic to tracks he built in his back yard. By the fall of 1964, he purchased and moved five other retired Pullman cars there, each 83 feet long and weighing about 85 tons.

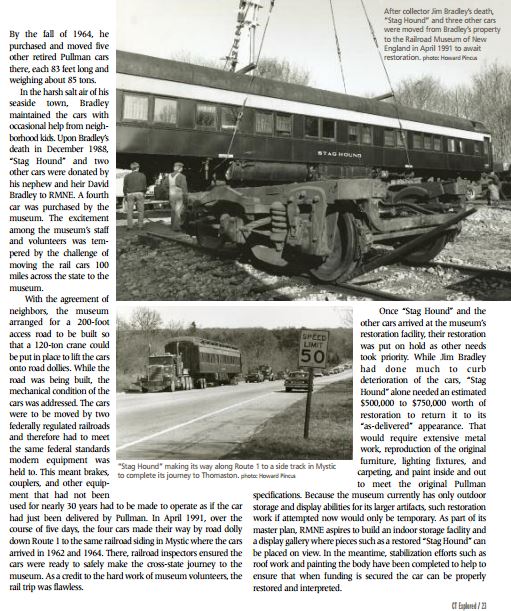

In the harsh salt air of his seaside town, Bradley maintained the cars with occasional help from neighborhood kids. Upon Bradley’s death in December 1988, “Stag Hound” and two other cars were donated by his nephew and heir David Bradley to RMNE. A fourth car was purchased by the museum. The excitement among the museum’s staff and volunteers was tempered by the challenge of moving the rail cars 100 miles across the state to the museum.

With the agreement of neighbors, the museum arranged for a 200-foot access road to be built so that a 120-ton crane could be put in place to lift the cars onto road dollies. While the road was being built, the mechanical condition of the cars was addressed. The cars were to be moved by two federally regulated railroads and therefore had to meet the same federal standards modern equipment was held to. This meant brakes, couplers, and other equipment that had not been used for nearly 30 years had to be made to operate as if the car had just been delivered by Pullman. In April 1991, over the course of five days, the four cars made their way by road dolly down Route 1 to the same railroad siding in Mystic, where the cars arrived in 1962 and 1964. There, railroad inspectors ensured the cars were ready to safely make the cross-state journey to the museum. As a credit to the hard work of museum volunteers, the rail trip was flawless.

Once “Stag Hound” and the other cars arrived at the museum’s restoration facility, their restoration was put on hold as other needs took priority. While Jim Bradley had done much to curb deterioration of the cars, “Stag Hound” alone needed an estimated $500,000 to $750,000 worth of restoration to return it to its “as-delivered” appearance. That would require extensive metal work, reproduction of the original furniture, lighting fixtures, and carpeting, and paint inside and out to meet the original Pullman specifications. Because the museum currently has only outdoor storage and display abilities for its larger artifacts, such restoration work if attempted now would only be temporary. As part of its master plan, RMNE aspires to build an indoor storage facility and a display gallery where pieces such as a restored “Stag Hound” can be placed on view. In the meantime, stabilization efforts such as roof work and painting the body have been completed to help to ensure that when funding is secured the car can be properly restored and interpreted.

The restoration of the Thomaston Station, on the other hand, has been done with a different curatorial goal in mind. The Naugatuck Railroad, a branch line, opened in 1849 and ran from Devon (part of Milford) through Waterbury and Naugatuck to Winsted. As was typical of the time, the railroad designed the stations on the basis of the size and prominence of the community. Cities such as Waterbury were provided with elaborate structures, while smaller hamlets’ stations could be as basic as a lean-to. Thomaston, situated along the Naugatuck River, initially had a modest station built in 1851 that served the town and two significant companies: the Seth Thomas Clock Company and the Plume and Atwood Manufacturing Company, a subsidiary of the American Brass Company.

The new station, built in 1881, was utilitarian in design and served a variety of functions. The northern portion of the building had a waiting room for travelers, complete with oak benches and a ticket window staffed with an agent. The southern portion included restrooms and a Railway Express Agency office (akin to today’s UPS). The station included one of the most important technologies of the day—a telegraph, allowing the town to stay apprised of the latest news. The 1851 station now served as a freight house.

The New Haven discontinued passenger service in December 1958, and the station was subsequently closed and sold. For the next 35 years the building housed a number of small cottage industries until 1993, when a disgruntled employee of one of those companies set a fire. Much as it had for “Stag Hound,” though, fate intervened. Members of the Thomaston Volunteer Fire Department were holding their weekly training session when the call came in. Thanks to their rapid response, damage was limited to the roof. For the next three years, though, snow and rain penetrated the building. During the winter of 1995, museum staff found three feet of ice on the floor of the waiting room. The property had become overgrown with brush, and the freight house had collapsed under the weight of a heavy snow. While many saw the station as ablight, members of RMNE saw it as a crucial artifact that needed to be preserved. Through generous donations by the Thomaston Savings Bank, the roof was replaced, making the building watertight and preventing further damage to the interior. Through work with the Connecticut Historic Trust for Historic Preservation, 1772 Foundation, the Dailey Foundation, and the State Historic Preservation Office, much has been accomplished, including being placed on the State Register of Historic Places. While restoration continues, the station is impressive as a restored space for the museum’s visitors, containing displays and exhibits and once again functioning as a working station for the museum’s demonstration passenger train excursions. Some of the museum’s rolling stock is on display next to the station and can be toured during open hours.

Brent Bette is a trustee of the Railroad Museum of New England and a history teacher at Simsbury High School.

Explore!

Railroad Museum of New England

242 East Main Street, Thomaston

860-283-7245, rmne.org

RMNE offers historic-train rides from April through December along the Naugatuck River valley, departing from the Thomaston Station built in 1881. Displays, exhibits, and some of the museum’s rolling stock are on view; programs are offered throughout the year on the history of rail travel throughout the region.

Connecticut Eastern Railroad Museum

55 Bridge Street, Willimantic

Open May to October. 860-456-9999, cteastrrmuseum.org

Connecticut Eastern Railroad Museum is on the original site of the Columbia Junction Freight Yard. Its collection includes rolling stock, buildings, and a six-stall roundhouse reconstructed on the original foundation. Guided tours and hands-on activities for kids are offered; a replica 1850s-style pump car operates along a section of the New Haven Railroad’s Air Line.

Danbury Railway Museum

120 White Street, Danbury

Open year-round. 203-778-8337, danbury.org/drm/

Located in the historic station and rail yard in downtown Danbury, the museum offers railroad history, rail excursions, a collection of original and restored rolling stock, and hands-on activities.

The Essex Steam Train and Riverboat

One Railroad Avenue, Essex

May to October. 860-767-0103, essexsteamtrain.com

The Valley Railroad Company, which operates the Essex Stream Train, leases the linear Connecticut Valley Railroad State Park along the Connecticut River from the State of Connecticut and offers visitors an early 20th century railroad experience including an 1892 freight station, steam locomotives, and vintage trains of historic cars. The nonprofit Friends of the Valley Railroad provides support for various projects.

Read all of our stories about travel & transportation history by clicking the category link at the top of the page