By Janice Mathews

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1904 Dr. Nathan Mayer (1838-1912) recorded his experience as a field doctor during the Civil War. Mayer was best known in Hartford as a gifted physician and a founder and staff member of St. Francis Hospital. He was also a poet and the music and drama critic for the Hartford Times.

But after studying in for 2 ½ years in Munich, Vienna, and Paris, he returned to the United States in 1862 and started his medical career as a field doctor in the Civil War. Despite a long-standing bias against Jews in the military at the time, Dr. Mayer, himself a Jew, apparently was well accepted and subject to no anti-Semitic behavior.

Treating a smorgasbord of infectious diseases and battle wounds, learning to ride a horse, and serving a stint in a Confederate prisoner of war camp were among the experiences that he recorded in a 1904 memoir. The following excerpt describes the challenges of treating Union soldiers and his experimentation with techniques he learned in Europe. Mayer’s memoir is available at the Library of the Hartford Medical Society (http://library.uchc.edu/hms/).

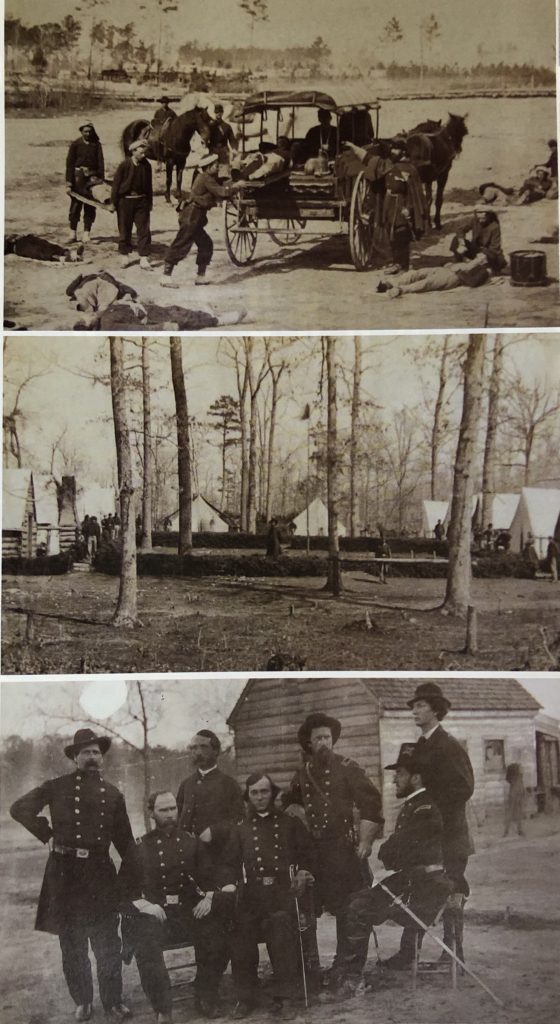

Top: Civil War ambulance. Middle: Civil War field hospital, Brandy Station, Virginia, showing the log barracks and tents Dr. Mayer mentions in his journal, March 1864. Bottom: Five surgeons from Connecticut are among this group of physicians who served in the Army of the James, Fort Harrison, Virginia, April 1865. Brady Collection of Civil War Photographs, State Archives, Connecticut State Library

In January 1862 I returned from a study-residence in Europe of 2 ½ years, having passed time chiefly in Munich, Vienna and Paris. In the latter city we already lived in the shadow of the great civil war, for, at the Theatre d’Anatomie, where many Americans had courses in operation under Prof. Rouet, there was a distinct division between northern and southern students, and those that before had loafed, studied and feasted together now heaped abuse upon each other. Bitter and caustic words fell even during instruction, so that it was impossible to think of anything but the mighty struggle across the ocean.

In March 1862 Mayer was commissioned Assistant Surgeon of the 11th Infantry Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers and went to North Carolina:

In 1862 the south was still full of marrow, rich in agriculture and the cities were elegant and fashionable. Our boys, who had endured much pain and stress at sea, on the storm-beaten transports around [Cape] Hatteras [North Carolina], and had wanted for many things, now ran riot in the land. The result was a great number of typhoids. I was at once in charge of 30 typhoid cases, housed partly in log barracks formerly occupied by the confederate soldiers, partly in the old mansion of a Governor of colonial days. I moved them into tents as soon as I could draw any, and organized a corps of nurses from the rough material of our boys. I assure you they were not bad. The American has faculty and these country boys carried out my Munich ideas better than they deserved. For I was the martinet. I tried to improvise a German hospital in an American camp till I saw my folly. In an ambulance I headed a party into the enemy’s country and brought in several cows…and had milk for my typhoids, better than the Borden condensed which was supplied in cans. I went into Newbern and unearthed some kegs of beer—in a German tinner’s shop—paid for them out of the hospital fund, and stimulated my patients Munich fashion.… Only two of the thirty died, one of utter exhaustion, the other of perforation.… The cooking was something awful, and I had to look to the kitchen daily, though I myself didn’t know anything of that department except by intuition.

But I had not alone typhoids. In a hospital tent ½ mile away in the woods were 25 small pox cases. At first only a few, then more, up to 25. The disease must have been brought along with the expedition. The milk and the water and the food were carried to the edge of the wood by my typhoid nurses 3 times a day, then the four negroes who attended the small pox cases came and got it. I was the only white person who went to the small pox tent.…my trunk was lost—so you saw me in a scarlet, much beflowered calico morning robe, my head tied up in a bandanna, stalking across the fields and into the woods to see my patients. In the huge pockets of the gown I brought medicine and dressings, and several of the patients who were not very sick, or already better, helped manfully in the care of the rest. The small pox people got no beer but whiskey—and this I had to give myself. I couldn’t trust the negroes.… After most of my convalescent patients had recovered, and a few convalescents had been placed in a general hospital established meanwhile at Newbern, I burned the entire outfit, and got to my regiment.

Mayer completed his service in 1865 and returned to Hartford, where he became known as one of the finest physicians in the area. He continued writing criticism for the Hartford Times until close to the time of his death, in 1912, of heart disease.

Janice Mathews is library liaison to the departments of Urban Studies, Humanities, Sciences, and Social Sciences at the Harleigh B. Trecker Library at the University of Connecticut, West Hartford, and is a member of the HRJ editorial team.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut in the Civil War in our two special issues, Spring 2011 and Winter 2012/2013 on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories about Connecticut health history in our Feb/Mar/Apr 2004 and Spring 2007 issues and on our Health & Medicine TOPICS page.