(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., WINTER 2015/16

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Mike Toner graduated from the New York Maritime College in 1965 with a B.S. in nuclear engineering and three options: a job in the bureaucracy at Knolls Atomic Power Lab in Schenectady, a graduate program in physics at Virginia Tech, and an engineering position at Electric Boat in Groton, Connecticut. Toner wasn’t ready to sit at a desk, and graduate studies seemed too academic. He chose Electric Boat, known locally as EB. Toner always loved a challenge, and the submarine shipyard would certainly offer that.

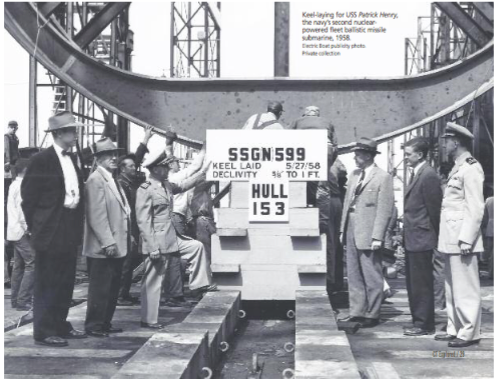

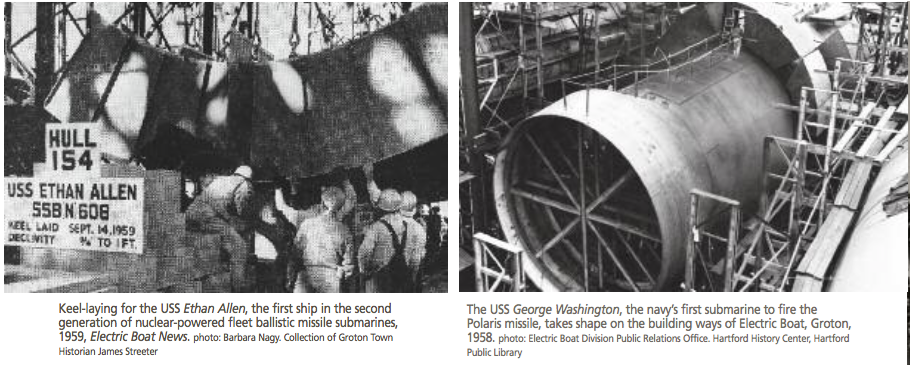

EB had launched the world’s first nuclear submarine, the Nautilus, in 1954. By the 1960s the Cold War was an everyday reality. EB was struggling to standardize construction methods and business processes so large numbers of ships could be built efficiently. The yard was stretching to meet the Navy’s rising expectations and help the men taking submarines to sea in the early years of the Cold War do their jobs and live underwater for weeks or even months at a time.

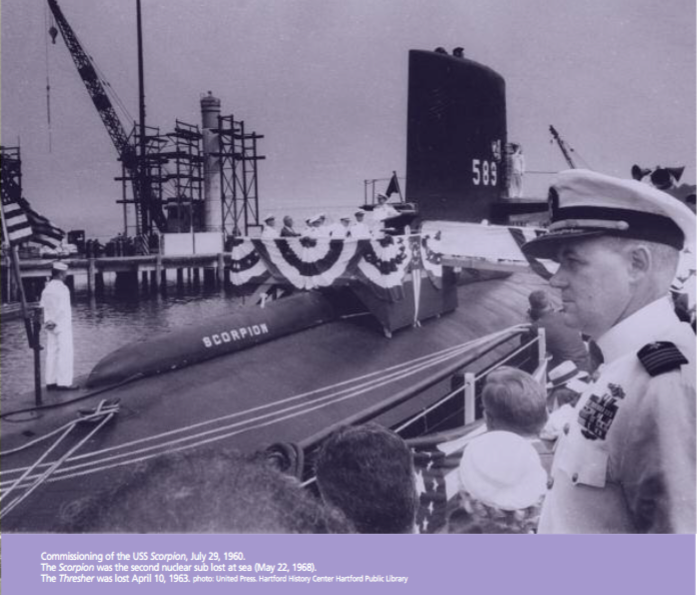

In that era, the company and its workers also wrestled with horrific tragedies, including the loss of 129 sailors in the sinking of the Thresher in 1963 and a fire that killed three EB workers on the Flasher the same year. As a result, EB developed a near-obsessive culture of accountability and dedication. After Thresher, no detail was too small to ignore. “Did you check it? Did you pay attention to it? Did you get it right? If you screwed it up, raise your hand. Say, ‘Hey, we gotta fix this,’” said Toner, EB’s president from 2000 to 2003.

The 1960s cemented Electric Boat as America’s premier designer and builder of nuclear-powered submarines. EB’s dominance would be challenged in the decades ahead. But by the end of the 1960s, it had established itself as a truly modern nuclear shipyard. Today its only real competition is Newport News Shipbuilding—whose primary work is construction of aircraft carriers.

With underwriting from Connecticut Humanities (CTH), I recorded the stories of 30 tradespeople, engineers, managers, and support staff—including Toner—who worked at the yard in the 1960s. I edited the interviews into excerpts for an exhibition at the Groton Public Library last fall as part of CTH’s “The Way We Worked” partnership with the Smithsonian Institution. A selection of condensed oral histories from that exhibition illuminating what it was like to work at Connecticut’s iconic submarine shipyard in the 1960s appears here.

“Come on Kid, Get out of the Way!”

Bob Rosso: Started in 1963 as a pipefitter

On my first day, it was just mind-boggling. They assigned me to work with somebody and I went up on a boat. The guy says to go get a tool. I couldn’t find my way out. And after I got out, I couldn’t get back. I had never seen anything like this.

We used to punch out on the hill. You’d run up and all the timecards would be on the wall. You’re there looking for your card and there’s guys behind you hollering and screaming at you, “Come on kid, get out of the way!” It was chaos.

[At first,] I didn’t think about safety. If you went into a ballast tank, you grabbed an air hose, a flashlight, and you went in and you did the job. Your boss knew you were in there and somebody working on the top might know.

We had some fatalities—one happened right after I got here. There was too much argon in the tank. The guy passed out and died.

Today the tank is tested first. We have tank-watchers. It’s not an OSHA requirement, it’s a requirement for us here. The union, we have five full-time safety reps per the contract and that’s all we do. The company has their safety reps too. It’s more proactive.

I Was Directing Traffic in the Sail

Bruce Caron: Started in 1958 as a machinist; retired as a supervisor

In 1965 I became a planner. My boss put me on salary, never even asked me. I expedited, laid out work, chased material. We had five, six submarines going at the same time.

I was in the sail on top of the submarines. Periscopes, fairwater planes. It becomes a congested area with everybody trying to work in there. So I laid it all out for them. Electricians would go in there. Machinists there, shipfitters here. I was directing traffic—I liked the work.

I got along good with the people. If you treated them halfway decent, they were good. If you didn’t, then you’d pay.

My brother worked at Electric Boat. My wife worked at Electric Boat. And every one of my kids worked at Electric Boat.

When I started, there were no women in the yard. I remember coming through a boat one night in the ’90s, this was on the Ohio class. They had these ventilation valves that were humongous. I come walking down, and I look. It’s my daughter.

I say, “What are you doing?”

She says, “I’m putting this valve in.” What?! And she did. The riggers were there and everybody else, but that was her job.

Jackie Kennedy Visits EB

Connie Stoddard: started in 1958 as a clerk; Retired in 1993 as a private secretary

On May 8, 1962, Jackie Kennedy—the First Lady—came to Electric Boat to christen the Lafayette. It was a big day. The six of us—the six clerks in the insurance department—were coat-check “girls.” It was a beautiful day and we arrived early so we would be in place.

Jackie glided across that floor, passed by me within less than three feet. She had her Jackie smile. It’s something you never forget.

Upstairs there were three rooms for Mrs. Kennedy and her contingent to freshen up. When they all left, the six of us went upstairs to see what the rooms were really like. The flowers were beautiful. I brought some of them home and pressed them. I still have the program and the invitation my mother and father received—he was an EB supervisor. I also have matches, napkins, and a coat-check stub.

I always wanted to be a private secretary, and I did become one. I enjoyed going to work every day because I was not just a secretary. I was one of the team.

The Legacy of the Thresher

Dan Hall: joined the design workforce in 1965

There is one school of thought that says that the Thresher sank because of the failure of a piping system. Prior to that there was only limited identification of piping joints. After Thresher we had to identify every joint. Every one of them was replaced on the boats that had been built since Thresher.

In the engine room area—I always worked engine room—there were probably a couple thousand of these. Most of these joints were drains off the bottom of a pipe. When you’re looking for them you don’t see them because the pipe can be close to the hull. I remember many, many years later being on ship checks over in Scotland and finding one. You had to replace that piece of pipe. It had been missed.

It was quite a cohesive group. We stuck together. We had birthday parties. We had Christmas parties. Weddings. Mostly everybody was young.

The Thresher went down with 129 souls. It gave me a very, very strong desire to do right by the sailors. Part of what I was teaching draftsmen later was that the specifications all go back to what happened on the Thresher. You can’t violate them.

My Goal? To be the Best Welder EB Ever Had

George Strutt: started as a welder on November 16, 1964

On my first day in the yard, I got assigned to the North Yard blocks. It was something like 5 below zero. It was cold and I was welding. I kept welding because it kept me warm. They gave me a job called tacking. As long as the piece held together it was good. You didn’t have to worry about any X-ray inspections or any defects in your weld. So they start you out slow.

I had a real good boss, Eddie Morenzoni. I remember him coming up to me and saying, “You’re going to learn how to weld now. I’m shipping you to the boats.” I was like, “Oh, okay,” because on the boats everything is tight. You’re in all sorts of odd positions and you really learn how to weld. And your work is very closely inspected.

There are a lot of different tricks to doing things. We used to do a lot of welding with mirrors. It’s like looking in a mirror and shaving but this time you’re welding and everything’s the opposite way. Later I used to tell the welders when I taught them, you learn to weld at EB and you can weld anywhere.

My goal was to be the best welder they ever had at Electric Boat. I wanted every qualification there was. I loved the challenge.

I got drafted to Vietnam in ’67. That’s when I found out how nice a guy Eddie Morenzoni was. When I was overseas he used to write me letters. We stayed in contact. That’s the way EB was back then.

I suppose I am a trailblazer

Jane Manley: 2nd female draftsman in EB history

I came back to New London in 1949 and was taken in as a third-class draftsman. The president of the union at that time told me that that was as far as I could think of going.

I said, “You’re full of it,” you know—to myself. I was cautious about what was going to happen to me and I just did my work.

I retired in 1989 as a top senior designer. I progressed because I knew what I was doing. At one point I was working with 700 men in the design department. I wasn’t surprised by what I accomplished. But I’m very proud of it.

I suppose I am a trailblazer, but I know so many women who worked at EB and work there now. They’re just as great as the men—especially my daughter.

We Listened to Tapes of Soviet Submarines

We Listened to Tapes of Soviet Submarines

Ken Brown: started in 1961 as a nuclear engineer; retired as vice president of operations

When I started, we didn’t have cubicles. There were just open desks all around. It was a room full of engineers. There was a lot of conversation back and forth because we had to work on things together. The others were for the most part my age or sometimes a little bit younger. I was in my mid-20s. Some of us became the best of friends.

Our work—the S5G project—was to make sure our submarines would be quieter so they couldn’t be picked up by the Russians. There was a real sense of urgency.

We always wanted to know that we were better than the Russians. We had noise tapes of their submarines. “You want to hear what a noisy feed pump sounds like? Listen to this one. Here’s ours. See how much better we are?”

I couldn’t tell my family much about what I was working on. They asked all the time. All the tech manuals, all the plans for the components, all the studies we were doing in R&D—the sound tapes and all that stuff—all that was classified. We kept it in our lockers. There were rows of them. These things were damn near bullet-proof.

The secretaries would come around before they left and check all the locks. I don’t know how it ever happened but every once in a while you’d just forget. And the dreaded thing was to come in and find a red lock on your locker, knowing you left it unlocked and you’d all have to get a big lecture.

The Foremen Were People Like my Father

Wayne Chiapperini: started in 1967 in nuclear engineering

My first boss was a man named Robert Holby—Bob Holby—and I thought so much of him, I named my first son after him. He was just a tremendous person. He guided me.

On the first day, they showed me around, all that stuff. At about noontime, Bob comes over and says, “Here’s a little project we’ve got to do. Work on it.”

Believe me, it was nothing. It was an angle iron holding a pipe or something. All I had to do was calculate the stress in the joint, the weld. My mind went blank. I know this is nothing. It’s just basic civil engineering, structural analysis, but I couldn’t break through that.

I’m sitting there and Bob came over. I said, “I don’t even know where to begin on this.” He goes, “Sigma equals M over A,” and then I just burst out, “Oh! Okay!” and it all just started coming together.

The general foremen were people like my father. They didn’t have the opportunity to go to college. They were smart people and they knew how to do their stuff. I learned so much. I owe them so much.

It’s the American Dream. Hard Work Does Pay.

Wayne Magro: started August 18, 1959 as an electrician; retired as a program manager

In the beginning, it was 10 hours a day, seven days a week. The 598 was getting ready to go to sea—that’s the George Washington, the very first Polaris ballistic missile submarine—and the Patrick Henry was going to be launched. Everything stamped “Polaris Action” had to move. It got priority because of the Cold War.

I worked on all those early boats that were pushing the limits. I knew there was something going on out there. That really motivated everybody, at least in my area, to work harder. I wasn’t going to go into the service, but this was my part. That was the culture. You worked hard.

After I got into management I probably put in 60, 65, 70 hours a week. My wife Nancy raised the five children with me gone all the time. Without her I wouldn’t have had a career at EB.

To me, it was the American dream. I went there with no education. Just hard work. I mean hard work. They were great to me. I appreciate that. I’m trying to pass this on to my grandchildren. Hard work does pay. Look at us.

Electric Boat was founded in 1899. Since 1952, it has been a subsidiary of General Dynamics. The first nuclear submarine, the Nautilus, was launched in 1954 (It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1982 and the Connecticut state ship in 1983; see “Site Lines: Connecticut’s State Ship,” Spring 2014.) For a detailed history of the many ups and downs of General Dynamics and Electric Boat, see the International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 40 (St. James Press, 2001), available online at fundinguniverse.com.

Electric Boat was founded in 1899. Since 1952, it has been a subsidiary of General Dynamics. The first nuclear submarine, the Nautilus, was launched in 1954 (It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1982 and the Connecticut state ship in 1983; see “Site Lines: Connecticut’s State Ship,” Spring 2014.) For a detailed history of the many ups and downs of General Dynamics and Electric Boat, see the International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 40 (St. James Press, 2001), available online at fundinguniverse.com.

Barbara Nagy covered Electric Boat for The Day of New London and The Hartford Courant from 1990 to 2003.