By Kevin McBride and Laurie Pasteryak Lamarre

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The arrival of Dutch traders in Connecticut in the early 17th century is the beginning of Connecticut’s immigrant story. The impact of Europeans on the well established Native American society was complex and within 25 years led to the devastating Pequot War.

During the early 17th century, approximately 8,000 Pequot lived within a 250-square-mile territory in southeastern Connecticut defined by the present towns of Groton, Ledyard, Stonington, and North Stonington and the southern portions of Preston and Griswold. In the early 1630s an epidemic of smallpox, introduced by Europeans, swept through northeastern North America, decimating Native populations. It reduced the Pequot population to 4,000 by the eve of the Pequot War in 1635.

By the 1630s, the Pequot exerted control across southern New England by subjugating dozens of Native tribes and communities through warfare, coercion, diplomacy, and marriage, forming a regional confederacy of allied and subjugated tribes. Pequot influence extended along coastal Long Island Sound from Fairfield, Connecticut to Charlestown, Rhode Island and eastern Long Island, and up the Connecticut River Valley to the present border with Massachusetts, and included all of eastern Connecticut. Subjugation of these areas was critical to establishing and maintaining control of the fur and wampum trade and the flow of European goods to Native allies.

The Pequot’s efforts to control territory outside their homeland reflects a high degree of socio-political and military organization. These developments correlate with the arrival of Europeans and are a clear departure from earlier patterns of intertribal warfare. The change does not reflect the European introduction of firearms or European concepts of warfare but rather the shifting cultural objectives for which Native peoples waged war.

During the period of Dutch dominance of the fur and wampum trade between 1611 and 1633, there was a time of relative calm in the Connecticut Valley as both the Dutch and Pequot benefited from their exclusive trading relationship and control of their respective economic and political spheres. The arrival of English traders in the Connecticut River Valley in the fall of 1633 sowed the seeds of the Pequot War. Tensions arose when the English sought to break the Dutch monopoly by establishing their own trade relations with tribes in the region while the Dutch and Pequot sought to maintain their control through force.

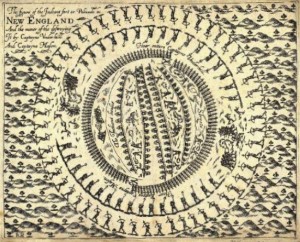

An artist’s rendering of a bird’s-eye view of the Battle of Mistick Fort, from John Underhill, Newes from America; or, a New and

Experimentall Discoverie of New England; Containing, a True Relation of their War-like Proceedings there Two Years Last Past,

with a Figure of the Indian Fort, or Palizado, 1638.

In the summer of 1634, Virginia trader Captain John Stone, Captain Walter Norton, and a crew of eight were sailing up the Connecticut River when Stone seized several Western Niantic Pequot allies to help guide them upriver. The details are not entirely clear, but whether in retaliation or rescue, the Pequot killed the entire crew. Although the Pequot provided explanations for the murders, all of which suggested they viewed their actions as justified, the English decided they could not let any English death go unpunished and demanded the culprits be handed over. A tentative peace treaty between the Pequot and Massachusetts Bay authorities was reached in fall 1634, but it did little to ease the increasing tensions between the Pequot and English (and Dutch) as the struggle for trade control continued.

By late summer 1636, the Pequot had not relinquished the murderers, and after the death of another English captain, John Oldham, off Block Island, Massachusetts Bay authorities sent an expedition of 90 men under Colonel John Endicott to exact retribution. The English force landed on Block Island, engaged the Manissesin battle, and then sailed to the Thames River. After fruitless negotiations, the English attacked and burned the village on the east bank, killing several Pequot. The Pequot viewed this action as unprovoked and in retaliation laid a seven month siege to the nascent English settlement at Saybrook Point.

In winter and spring of 1636-1637, the Pequot attacked whoever ventured from the safety of the Saybrook Point palisade, destroyed provisions, burned warehouses, and generally interrupted river traffic with Windsor, Wethersfield, and Hartford. The Pequot pursued diplomatic initiatives with neighboring tribes to enlist their aid against the English. More than 20 English were killed at and near Saybrook Point and along the lower Connecticut River during the siege. By April 1637, Massachusetts Bay Colony sent 20 soldiers under Captain John Underhill to relieve the siege, and the Pequot shifted their attention to other Connecticut River settlements.

On April 23, 1637, the Pequot attacked English settlers at Wethersfield, killing nine men and two women and capturing two girls. The attack galvanized the English; in response, the General Court on May 1 ordered an “Offensive War against the Pequot,” as recorded in The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut (Brown and Parsons, 1850) and levied 90 soldiers from Hartford, Windsor, and Wethersfield for an expedition against the Pequot. The expedition was commanded by Captain John Mason, who was ordered to land his men along the Thames River and conduct a frontal assault on two fortified villages at Weinshauks and Mistick. The English sailed to Saybrook Point, where Mason conferred with Lieutenant Lion Gardiner, commander of Saybrook Fort, and Captain Underhill as to the best way to conduct the campaign. Gardiner’s and Underhill’s previous experiences fighting the Pequot resulted in a change of battle plan from a frontal assault to a nighttime or dawn surprise attack.

Before attacking the Pequots, the English enlisted Mohegan, Wangunk, and other River Indian allies. As they sailed to Narragansett, an additional 250 Narragansett joined the force. Together, the force totaled 77 English and more than 300 Natives. They marched over 20 miles west through Niantic (present-day Charlestown, Rhode Island) and Pequot country (Stonington) and encamped near the head of the Mystic River on the evening of May 25. Their encampment was only two miles from the fortified village at Mistick—close enough to hear the Pequot singing.

In the early morning of May 26, the force marched to Mistick Fort at the summit of Pequot Hill, half a mile west of the Mystic River. The attack began at dawn, and within two hours more than 400 Pequot men, women, and children lay dead, 200 of them burned to death. Between 150 and 200 Pequot warriors— among them reinforcements from other villages who had arrived the night before—were killed in the attack. The Pequot continued to counterattack the retreating English-allied forces throughout the day as they withdrew eight miles west to meet their ships in the Thames River. The English reported that they killed more Pequot in these counterattacks than at Mistick Fort. With the attack and the loss of so many individuals, the surviving Pequot shortly thereafter abandoned their villages and sought refuge with neighboring tribes and a continuance of war against the English.

In the early morning of May 26, the force marched to Mistick Fort at the summit of Pequot Hill, half a mile west of the Mystic River. The attack began at dawn, and within two hours more than 400 Pequot men, women, and children lay dead, 200 of them burned to death. Between 150 and 200 Pequot warriors— among them reinforcements from other villages who had arrived the night before—were killed in the attack. The Pequot continued to counterattack the retreating English-allied forces throughout the day as they withdrew eight miles west to meet their ships in the Thames River. The English reported that they killed more Pequot in these counterattacks than at Mistick Fort. With the attack and the loss of so many individuals, the surviving Pequot shortly thereafter abandoned their villages and sought refuge with neighboring tribes and a continuance of war against the English.

THE BATTLEFIELDS OF THE PEQUOT WAR PROJECT

After more than 375 years, the Pequot War (1636-1637) remains one of the most controversial and significant events in the colonial and Native history of America. The Battlefields of the Pequot War project, a collaboration begun in 2007 by the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center and University of Connecticut, seeks to expand our knowledge and understanding of the Pequot War in a broader historical and cultural context. Historical research focuses on the political, social, and economic causes and consequences of the war and on the complexity of intertribal, inter-colonial, and Native-colonial relations of the period. Using traditional archaeological and historical methods and a variety of geophysical techniques such as metal detecting, ground penetrating radar, and electrical resistivity, the project has resulted in new perspectives and initiated the preservation of Pequot War battlefield sites.

The discipline of battlefield archaeology involves identifying and documenting places where conflict has taken place through an analysis and integration of the historical and archaeological records. This process relies on primary accounts, which give information on troop dispositions, weapons, tactics, and the order of battle (i.e. disposition of personnel and equipment of an armed force during field operations) along with undocumented evidence gathered from archaeological investigations. The archaeology of a battlefield allows for reconstruction of the battle’s events and the assessment of the veracity of the primary accounts and fills gaps in the historical record. This is particularly important with respect to the Pequot War battlefields, as the record is often incomplete, confusing, and biased. Battlefield archaeology seeks to move beyond a simple spatial reconstruction toward a more dynamic interpretation of the battlefield that involves reconstructing events and actions across time and space.

The Battlefields of the Pequot War project is investigating sites of events and actions between August 1636 (Endicott’s Massachusetts Bay raid of Block Island Manisses and Thames River Pequot villages) and August 1637 (the capture of Pequot leader Sassacus near Dover Plains, New York). Additional sites/events are: the Pequot attack on Wethersfield (April 1637), the Battle of and Retreat from Mistick Fort (May 1637), the Battle of the Northeast (July 1637), and the Fairfield Swamp Fight (July 1637).

MISTICK FORT BATTLEFIELD RECONSTRUCTION

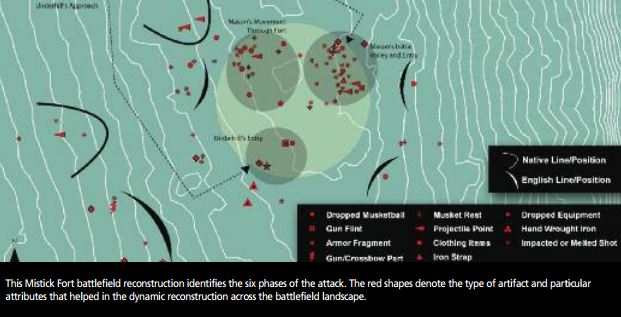

Drawing upon both the historical and the archaeological record, researchers have identified not only the boundaries of Mistick Fort but areas where individual actions and movements took place during the battle.

English Allied Forces’ Approach to Mistick Fort

The plan of attack was for the English to surround Mistick Fort, fire an initial volley, and then force their way through the northeastern and southwestern entrances “to destroy them by the Sword and save the Plunder,” as Mason’s posthumously published account A Brief History of the Pequot War (S. Kneeland & T. Green, 1736) recorded. The English divided their 77 soldiers into two “divisions” of approximately 38 men each under Mason and Underhill. Mason’s division approached Mistick Fort directly from the north to surround the fort to the northeast, while Underhill approached the fort slightly to the west of Mason to surround the fort to the southwest. The Native allies were to form a ring outside the English to prevent any Pequot from escaping.

Captain John Mason’s Initial Volley

The plan was to fire a volley simultaneously after each division surrounded the fort. However, Mason’s division was discovered before either was positioned. Upon discovery, Mason quickly approached the fort, ordering and firing a volley through the palisade. The archaeological signature of Mason’s initial volley is a concentrated pattern of lead in the northeast quadrant (rather than an evenly dispersed pattern around the fort, which would result from an English-fired volley from their planned surrounding positions).

Mason’s Entry and Fight in Northeast Quadrant of Mistick Fort

Mason’s division entered the fort after the initial volley. Mason managed to achieve a degree of surprise, and his entry into the fort with 17 of his men was uncontested until the English began to engage the Pequot in the wigwams. Based on the pattern of non-musket-ball battle-related artifacts from the northeast quadrant, the fighting was a combination of hand-to-hand combat and musket fire from positions near the entrance. Two recovered musket rests, along with a flintlock sear mechanism, brass buttons, broken equipment, and Pequot brass arrow points attest to the intensity of fighting in this area of the fort. The narrative of an unknown soldier reported that several of the English were wounded so severely, with additional reports of men shot in their body and extremities, that some soldiers were carried on stretchers during the retreat, “some of them with the heads of the arrows in their bodies.”

Mason’s Movement and Fight in Northwest Quadrant of Fort

Mason’s narrative has him walking from one end of the fort to another down a narrow lane formed by wigwams arranged in a linear pattern. He mentioned “many Indians in the lane or street” and pursued them, describing close-quarter fighting at the end of the lane opposite the northeast entrance. The assemblage of battle-related artifacts in the northwest quadrant is quite different from that associated with the actions in the northeast quadrant of the fort. Of the 17 objects recovered, 16 were musket balls, with 1 impacted brass projectile point. This pattern suggests the English altered their tactics once inside the fort, using larger-diameter musket balls to target individuals who were at greater distances.

Mason’s Traverse to Northeastern Entrance, Firing the Fort, and Exit

After this action, Mason marched back down the lane to the northeast entrance, where he saw two soldiers exhausted, their swords pointing to the ground. He decided, “we should never kill them after that manner”—in reaction to difficulties of fighting in such close quarters and the high number of casualties suffered by the English (half of the 17 men who entered the fort with Mason were killed or wounded within 15 minutes)—and so set fire to the fort and exited.

Underhill’s Entry and Fight

Underhill’s narrative and battle-related artifacts recovered from the southwest entrance indicate his division gained entry into Mistick Fort and engaged Pequot warriors for only a short time —after Mason had set the fort on fire. Only four battle-related artifacts were recovered from the southwest quadrant: a dropped carbine or musket ball, a gunflint, a fragment from a pikeman’s armor, and a hand-wrought iron hook (commonly associated with accoutrements). Underhill’s attempt to enter the fort was hotly contested, and his contingent also suffered quick casualties.

Redeployment and Fight in Western Quadrant of Battlefield

Redeployment and Fight in Western Quadrant of Battlefield

When Mason exited the fort, his detachment joined Underhill in the southwest quadrant outside the palisade. The nature and distribution of objects outside the fort is consistent with the reconstruction of the actions and positions during the final phase of the battle. English positions, individual and unit, were identified based on the location of dropped musket balls and equipment assemblages. The presence and positions of the Native allies were identified based on recovery of triangular and conical brass arrow points outside the fort walls. The locations of these points are consistent with primary accounts, including Underhill’s depiction in print of the battle. The Native allies encircled English positions surrounding the fort.

The density and distribution of impacted musket balls, arrow points, and dropped and broken equipment indicate intense fighting over a large area. Native-allied lines are marked by brass arrow points, both conical and flat. English positions (identified by a concentration of weapons and equipment) were located in the southwest quadrant of the battlefield approximately 150 feet from the palisade entrance, a strategic placement to intercept fleeing Pequot. Collectively, the nature, distribution, and direction of fire of projectiles, equipment, and weapons indicate a chaotic melee, an intense battle acrossthe west half. The hand-to-hand fighting reported by sources is represented by the recovered artifacts of broken equipment.

BEYOND THE BATTLEFIELD

The Pequot War forever changed the political and social landscape of southern New England, and its events, specifically the “massacre” at Mistick Fort, demonstrated to all Native peoples of the region the political will and technological ability of the English to wage total war against Native people. The defeat of the Pequot created a power vacuum that initiated 40 years of intertribal warfare as other Native tribes sought dominance in the region. Many Pequot War historians simply undervalued the sophistication of the planning of English soldiers who participated in the Mistick Campaign. The English success at Mistick, and for the remainder of the war, was previously attributed primarily to superior military technology. In fact, English successes were achieved through a combination of intelligence gathering, careful planning, prior military experience, and tactical adjustments based on encounters at Thames River, Saybrook Fort, and Wethersfield. New research shows that nearly one-half of the soldiers had previous combat experience from service under English regiments during the Thirty Years War (1618- 1648) in the Low Countries. The prior experience of hardened veterans contributed to the defeat of the Pequot at Mistick.

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center continues to identify additional battlefields of the Pequot War with support from the National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program. In 2013, archaeological work at both the site of the English retreat from Mistick Fort and the original Saybrook Fort will further define events of the war across the Connecticut landscape.

Explore!

“Remembering the Pequot War in Fairfield,” Winter 2014-2015

Read all of our stories about Native Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS page

Read all of our stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page