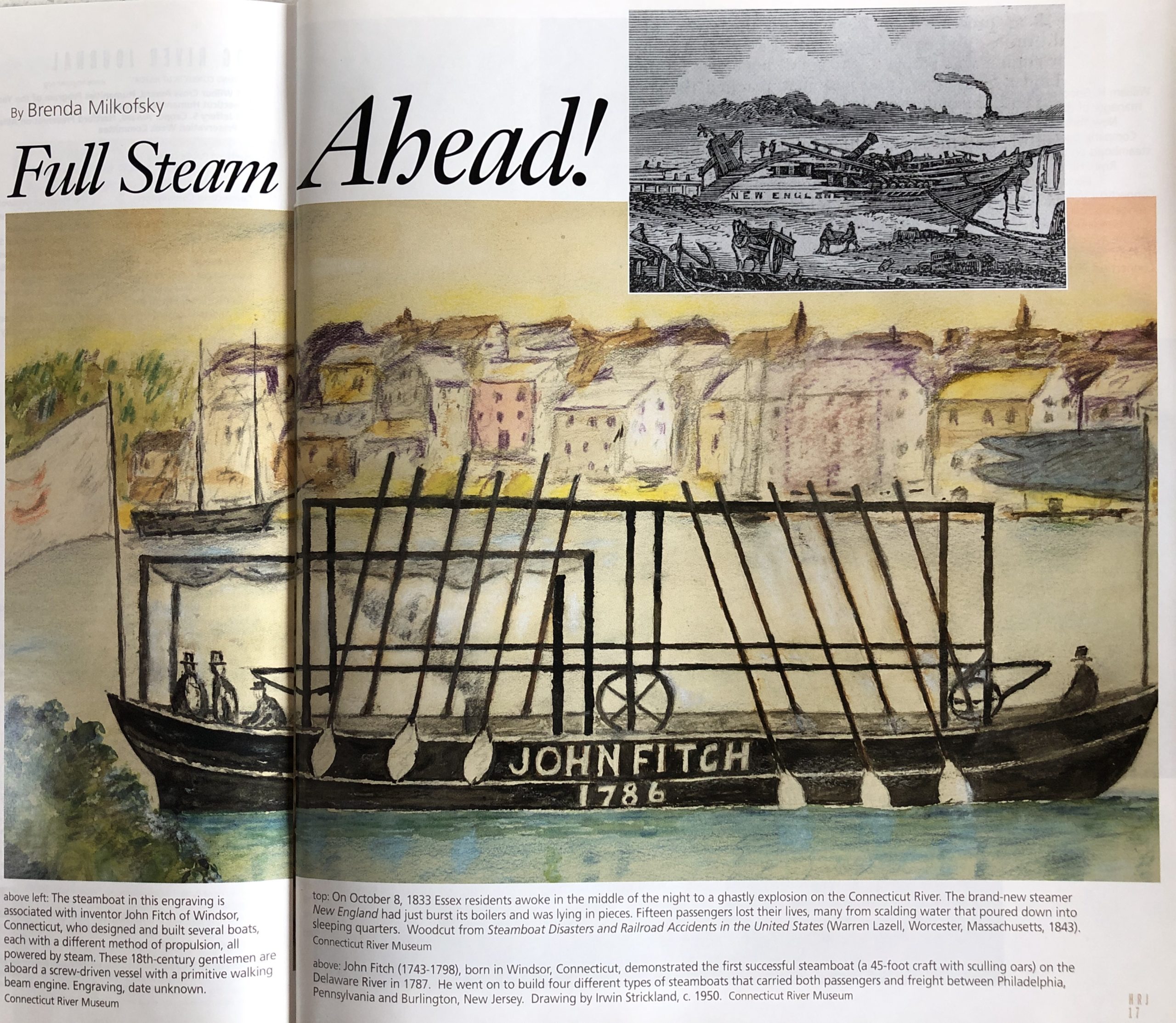

inset top: Woodcut from “Steamboat Disasters and Railroad Accidents” (1843), of the explosion of the brand-new “New England” in Essex, October 8, 1833. Large image: John Fitch, born in Windsor, demonstrated the first successful steamboat on the Delaware River, 1787. Drawing by Irwin Strickland, c. 1950. Connecticut River Museum

By Brenda Milkofsky

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Long Island Sound was a perfect place to foster development of the steamboat as a revolutionary mode of transportation. This protected inland sea is almost 100 miles long, and its northern shore, dominated by the Connecticut coastline, is dotted with populous ports. At one end sits New York City, which during the early 19th century grew into the nation’s distribution center for western wheat and foodstuffs for eastern cities. Just beyond the other end lay Boston and the cluster of manufacturing centers in its orbit. Textiles and shoes from Massachusetts’s burgeoning factories were shipped to New York for points west or abroad.

Both New York and Boston were well served by a sailing merchant marine, but the passage between the two cities was subject to the vagaries of wind and weather and took between three and five days, if one could get out of harbor at all. The fastest route by stagecoach from New York went north from New Haven to Hartford and on to Boston, but that trip took a teeth-jarring 48 hours, and stagecoaches and other over-land conveyances had a limited capacity for freight

These 18th-century gentlemen are aboard a screw-driven vessel with a primitive walking beam engine. Engraving, date unknown. Connecticut River Museum

The English and the French developed steam as a source of power, but it took America with its long rivers and vast hinterland to fully develop the steamboat. Two men from the Connecticut Valley, John Fitch of Windsor, Connecticut and Samuel Morey of Orford, New Hampshire, each developed a steamboat during the 18th century. John Fitch (1743-1798) demonstrated the first successful steamboat on the Delaware River in 1787, a 45-foot craft with sculling oars. He went on to build four different types of steamboats that carried both passengers and freight between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Burlington, New Jersey. In the early 19th century, Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston, experimenting on the Hudson River, became the first to demonstrate the commercial possibilities of steam transportation. In 1813 the Fulton poked her nose into Long Island Sound, but the British blockade and the War of 1812 kept her tied up until after the peace in 1815, when she began service from New York to New Haven, the first regular service on the Sound. Regularly scheduled trips took between 8 and 12 hours and cost six dollars.

Steamboats were such an improvement over sail that demand for their services expanded rapidly. After the New York State-approved Fulton-Livingston monopoly in New York waters was struck down in 1824 in Gibbons V. Ogden, steamboat lines blossomed everywhere. Six lines quickly formed in Connecticut, with vessels sailing from Bridgeport, Norwalk, New Haven, Hartford, Norwich, and Stamford to New York. Fierce competition over routes, rates, and schedules drove the fare from Hartford to New York down to 25 cents, meals included.

With boilers filled with scalding water under pressure, steamboats were inherently dangerous. On October 8, 1833 Essex residents awoke in the middle of the might to a ghastly explosion on the Connecticut River. The brand-new steamer New England had just burst its boilers and was lying in pieces. Fifteen passengers lost their lives, may from scalding water that poured down into sleeping quarters. [See “What a Disaster!” Fall 2011.] After several horrific accidents occurred, Congress passed The Steamboat Act of 1852 requiring construction standards, inspections, and measures to prevent fire and collisions.

After the Civil War, fashionable, floating palaces with crystal chandeliers, rosewood settees, and fine dining accommodations were introduced. An expanding middle class traveled by steamer to New York and Boston but also to a host of new hotels, picnic groves, and seaside resorts.

Manufacturers found steamboats a fast and cost effective way to ship freight. Once the powerful railroads crisscrossed Connecticut in the mid-1850s, the railroad companies began to acquire the steamboat lines. Railroads and steamboats worked in tandem until the Depression and bankruptcy doomed these “Victorian Ladies” forever.

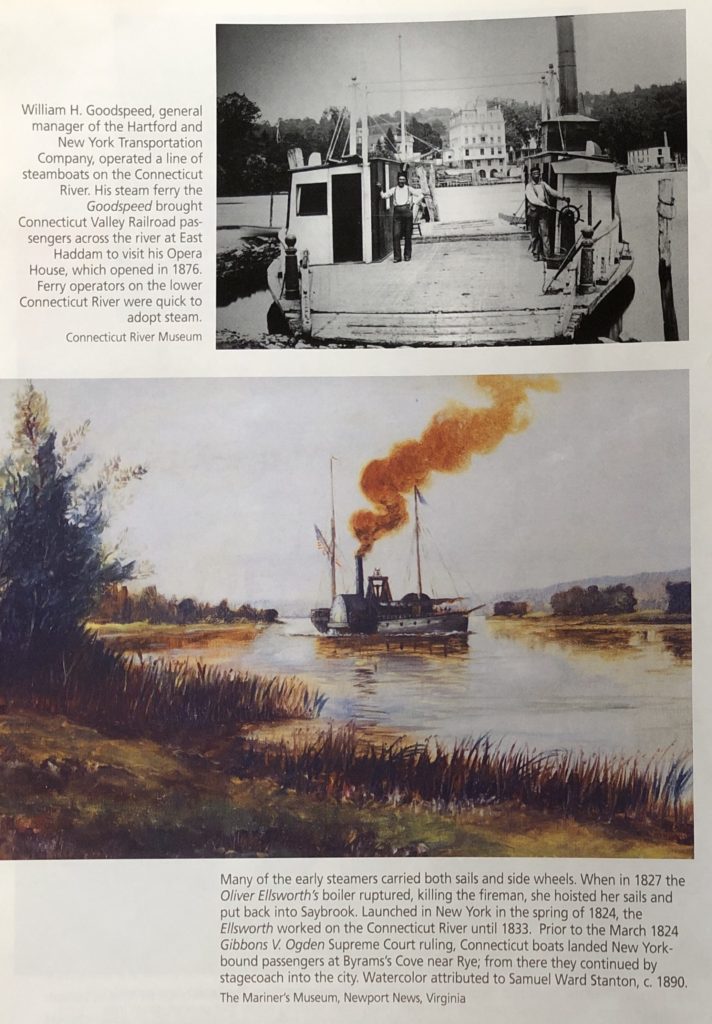

below: William H. Goodspeed, general manager of the Hartford and New York Transportation Company, operated a line of steamboats on the Connecticut River. His steam ferry the Goodspeed brought Connecticut Valley Railroad passengers across the river at East Haddam to visit his Opera House, which opened in 1876. Ferry operators on the lower Connecticut River were quick to adopt steam. Connecticut River Museum

above: Many of the early steamers carried both sails and side wheels. When in 1827 the Oliver Ellsworth’s boiler ruptured, killing the fireman, she hoisted her sails and put back into Saybrook. Launched in New York in the spring of 1824, the Ellsworth worked on the Connecticut River until 1833. Prior to the March 1824 Gibbons V. Ogden Supreme Court ruling, Connecticut boats landed New York-bound passengers at Byrams’s Cove near Rye; from there they continued by stagecoach into the city. Watercolor attributed to Samuel Ward Stanton, c. 1890. The Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia

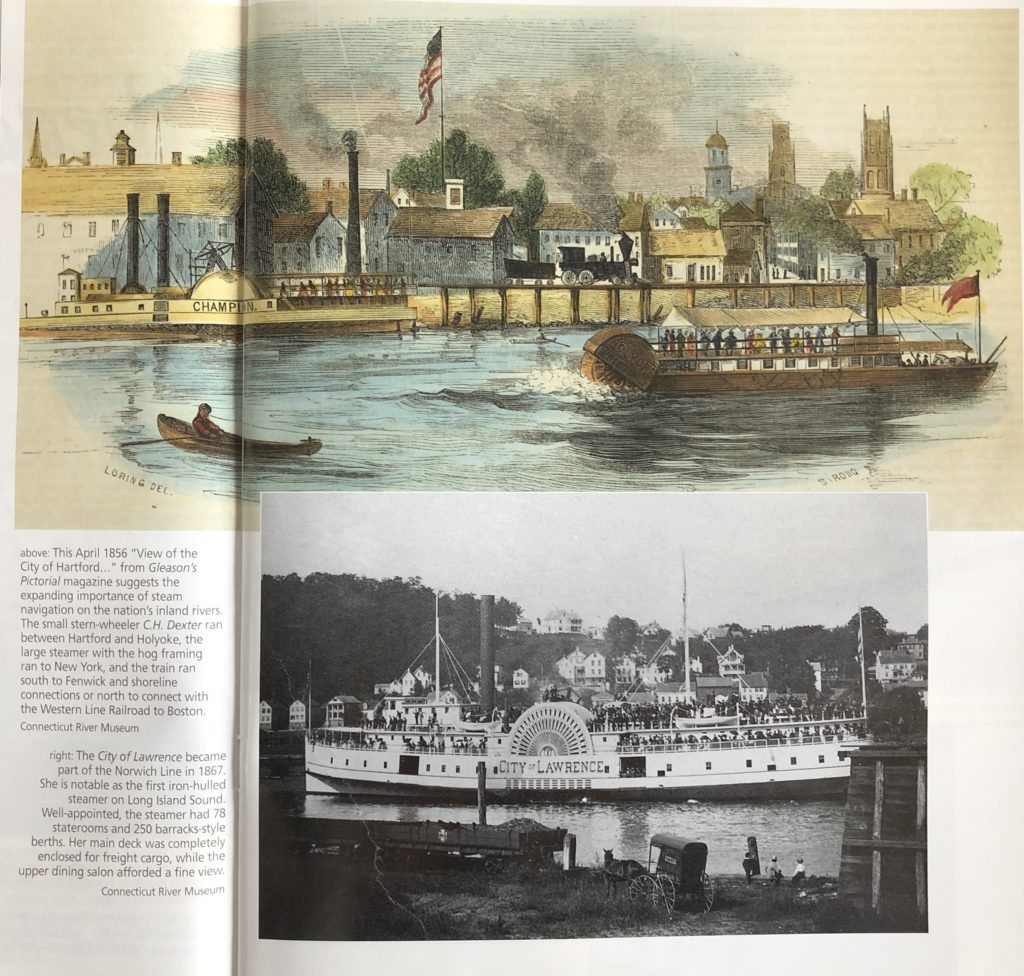

below: This April 1856 “View of the City of Hartford…” from Gleason’s Pictorial magazine suggests the expanding importance of steam navigation on the nation’s inland rivers. The small stern-wheeler C.H. Dexter ran between Hartford and Holyoke, the large steamer with the hog framing ran to New York, and the train ran south to Fenwick and shoreline connections or north to connect with the Western Line Railroad to Boston. Connecticut River Museum

above: The City of Lawrence became part of the Norwich Line in 1867. She is notable as the first iron-hulled steamer on Long Island Sound. Well-appointed, the steamer had 78 staterooms and 250 barracks-style berths. Her main deck was completely enclosed for freight cargo while the upper dining salon afforded a fine view. Connecticut River Museum

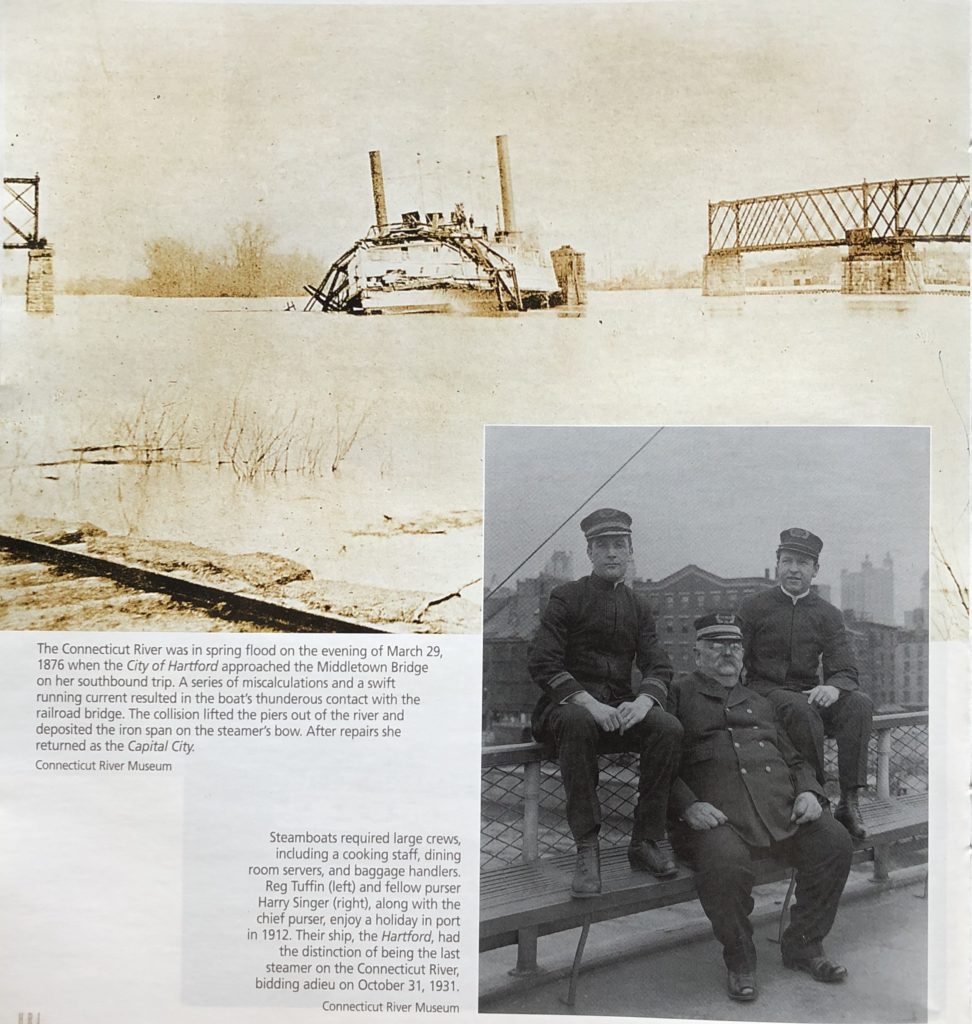

below:The Connecticut River was in spring flood on the evening of March 29, 1876 when the City of Hartford approached the Middletown Bridge on her southbound trip. A series of miscalculations and a swift running current resulted in the boat’s thunderous contact with the railroad bridge. The collision lifted the piers out of the river and deposited the iron span on the steamer’s bow. After repairs she returned as the Capital City. Connecticut River Museum

above: Steamboats required large crews, including a cooking staff, dining room servers, and baggage handlers. Reg Tuffin (l) and fellow purser Harry Singer (r), along with the chief purser, from the Hartford, enjoy a holiday in port in 1912. By the time this Hartford came on the Connecticut River in 1899, many area residents were using the railroad to connect with larger cities along the seacoast. The Hartford had the distinction of being the last steamer on the Connecticut River, bidding adieu on October 31, 1931. Connecticut River Museum.

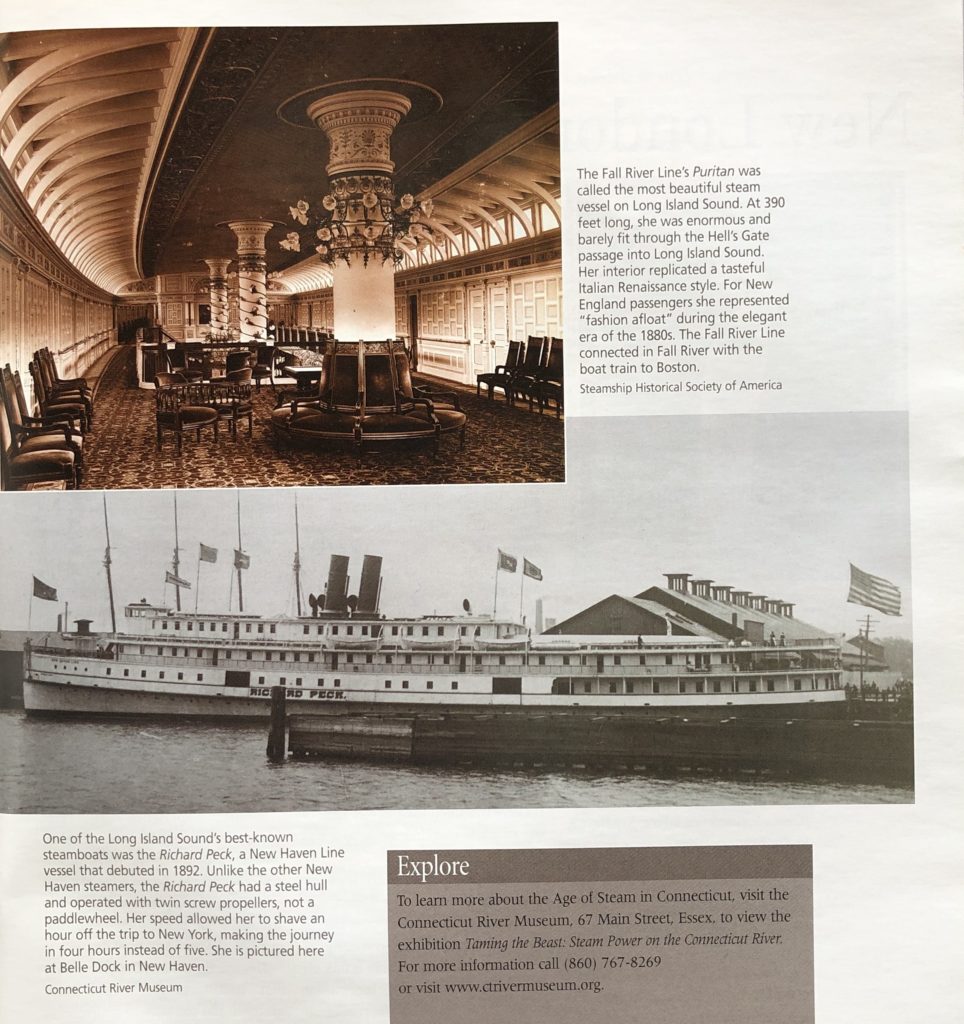

below: The Fall River Line’s Pilgrim was one of the most beautiful steam vessels on Long Island Sound. At 390 feet long, she was enormous, just fitting through the Hell’s Gate passage into Long Island Sound. Pilgrim was the first to be lighted throughout by electricity, provided by an auxiliary steam generator. Three great “electroliers” hung from an overhead dome. Pilgrim carried New York passengers to Fall River, Massachusetts where they connected with the boat train to Boston. New Haven Museum and Historical Society

above: One of the Long Island Sound’s best-known steamboats was the Richard Peck, a New Haven Line vessel that debuted in 1892. Unlike the other New Haven steamers, the Richard Peck had a steel hull and operated with twin screw propellers, not a paddlewheel. Her speed allowed her to shave an hour off the trip to New York, making the journey in four hours instead of five. She is pictured here at Belle Dock in New Haven. Connecticut River Museum

Explore!

Read all of our stories about Connecticut’s Maritime History on our TOPICS page.

“What a Disaster!” Fall 2011

The underwater find of the steamer Isabel: “Finding Isabel,” Spring 2018