by Elizabeth Lewis

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

A woman living in the mid-19th century would not likely decompress from a stressful day by going out for a long run or playing a game of softball with friends. But she might have done some of the exercises Catharine Beecher promoted in her 1855 publication Letters to People on Health and Happiness or illustrated in her 1858 fitness manual Physiology and Calisthenics for Schools and Families. In the evening, she may have attended a lecture by Dr. Dio Lewis at Beecher’s Hartford Female Seminary and listened as he acknowledged the “prejudice against gymnastic exercises for females.”

Beecher and Lewis were among the leaders of a reform movement aimed at improving women’s health through physical activity. Physical culture, as it was referred to, would promote individuality and foster intellectual pursuits. In schools, young girls were introduced to calisthenics, a relatively new program of movements calculated to develop the body’s frame. Accompanied by music, indoor calisthenics classes were performed as public exhibitions in town halls and school gymnasiums before crowds of parents and friends. Over time, school board administrators sought to have well-lit gymnasiums built and equipped with the “fine apparatus” calisthenics required.

At the same time, the emergence of a middle class opened up educational opportunities to American girls and women. By the end of the 19th century, about a third of college students were women. They pursued studies such as architecture, literature, and medicine and entered professions formerly held exclusively by men. As interest in physical activity increased, many women became physical educators in the belief that women might influence other women’s wellness better than men could.

In May 1895, The Hartford Courant reported, “Hartford was treated yesterday to the unusual sight of a party of women bicyclists in bloomers, the real genuine bifurcated garment such as are popularly alleged to be worn by the consorts of hen-pecked husbands.” This “unusual sight” would become more common, as would the participation of women in other sports such as tennis and golf. “On all sides, we hear testimony to the health-giving qualities of the Scotch sport [golf], women especially declaring they have been ‘made-over’ since taking it up,” noted The Courant in November 1896. But cycling, tennis, and golf weren’t the only new sports women were beginning to play

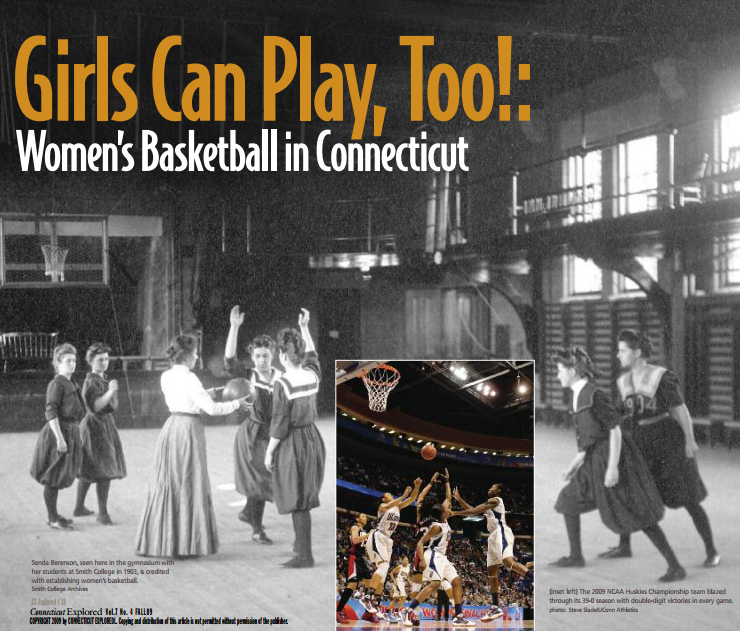

Just up the road from Hartford, Senda Berenson, a graduate of the newly established Boston Normal School for Gymnastics, had taken a position as a gymnastics instructor at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. A passionate proponent of physical education, Berenson believed it important for her students to “develop good sportsmanship and moral as well as physical courage.” Her mission was to “arouse [girls’] enthusiasm for health habits and those values that would serve most in later life.” She felt group athletic activity would foster decision-making, endurance, and cooperation. But few team sports were then available for women. When in the spring of 1892 Berenson read about “basket ball,” a new game Dr. James Naismith of Springfield, Massachusetts, had developed for boys, she decided to introduce it to her students—but with some changes.

Like many physical educators at the time, Berenson believed women’s reproductive organs somehow made their nervous systems fragile and that aggressive behavior could be harmful, making it more difficult for them to bear children. A rough game might over-stimulate a girl, straining her smaller heart, while playing in an aggressive, masculine manner might diminish her feminine qualities. Berenson also questioned whether young girls had the strength and stamina to play by the rules Naismith had established. So Berenson adapted those rules, while at the same time prohibiting excessive roughness and encouraging teamwork. She divided the court into three sections and assigned each player to a zone from which she could not move. Players couldn’t dribble more than three times, they could hold the ball for only three seconds, and they were not allowed to steal the ball.

Teams consisted of five to nine players. Some saw Berenson’s rules as stifling, while others felt they protected young women’s grace and femininity. Ironically, Berenson’s intent to protect the young women was foiled at the first game, played in March 1893. When Berenson threw the first ball at center court to launch the game between the freshman and sophomore teams, her hand hit the freshman captain’s raised hand and dislocated the player’s shoulder. The girls went on to play a powerful game. Afterward, one player said, “It was great fun and very exciting, especially when we got knocked down, as frequently happened.”

In 1899, the American Association for the Advancement of Physical Education met in Springfield and officially approved Berenson’s rules for women’s play. Two years later, Spalding Athletic Library published the first women’s basketball rulebook. Berenson would edit it for the next 17 years, keeping it up to date even as the rules changed considerably.

Women proved to possess a natural aptitude for basketball, and enthusiasm for the game spread rapidly throughout the country—and in Connecticut. In 1895, freshman girls at South Manchester High School decided to play the game during their gymnastics class. Two weeks later, intrigued by the fun the girls were having, the boys formed their own team and asked the girls to teach them to play. When they found out that they were playing by the girls’ rules, they switched to the boys’ rules. The following year, official teams for each class were formed. The boys’ teams played other local teams, but the girls only played games with classmates in the high school (in what were known as intramural games).

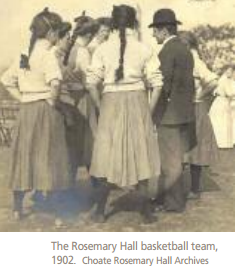

Basketball was conceived as an indoor sport, but the game quickly migrated outdoors. In a Harper’s Bazaar article published in February 1, 1896, Jean Pardee wrote, “To thoroughly appreciate the game you should see it played by young women on a meadow court. Then it is that its true value as a promoter of health and an inducer of good animal spirits is made apparent.” Harriet Spencer, an 1899 Rosemary Hall graduate, recounted her first basketball game in a letter to a friend. By then, the school had established rivalries with other schools. “Do you remember how Rosemary happened to start Basket-Ball?” Spencer wrote. “The Anderson Gym sent us a challenge to play them a month from the day we got theirs and we accepted. Then we wrote to Spalding for rules and equipment. We practiced with the small boys of the Choate School and beat the Anderson Gym in New Haven. Anne Rotan was the heroine of the game and I broke a toe, but we never again had a victory that thrilled us so much.”

In the sport’s early years, coaches and players had to contend with concerns about modesty and propriety. Some teams only played in front of a school audience. In 1901, Principal Peterson of Windham High School objected to a game of girls’ basketball scheduled at the Valley Street Armory, saying it amounted to the spectacle of “girls giving a public exhibition before a mixed company.” Berenson would post a notice on the gym doors forbidding “gentlemen” to attend the girls’ games. In 1906, two girls’ basketball teams at the Gilbert School in Winsted disbanded because some of the players’ mothers forbade their daughters to wear bloomers in public.

In the sport’s early years, coaches and players had to contend with concerns about modesty and propriety. Some teams only played in front of a school audience. In 1901, Principal Peterson of Windham High School objected to a game of girls’ basketball scheduled at the Valley Street Armory, saying it amounted to the spectacle of “girls giving a public exhibition before a mixed company.” Berenson would post a notice on the gym doors forbidding “gentlemen” to attend the girls’ games. In 1906, two girls’ basketball teams at the Gilbert School in Winsted disbanded because some of the players’ mothers forbade their daughters to wear bloomers in public.

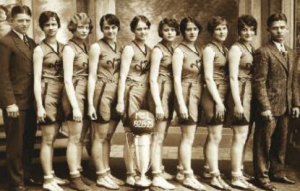

This modesty dissipated over time. The 1916 Naugatuck High School yearbook recorded that the girls’ basketball team, which played in public, was “all decked out in the latest sportswear—middy blouses and the garment made famous by Amelia Bloomer—bloomers!” Basketball “costumes” or uniforms evolved over time, and teams in different parts of the country adopted their own versions of game attire.

At first, players wore handmade knicker-style bloomers and middy tops or sport shirts in their school colors. Many players wore side combs and hair ribbons, and it was not uncommon for a game to stop as girls scrambled to pick up their hair fasteners. By the mid 1920s, players were wearing knee-pads and a shorter version of bloomers. In just a few years, women would sport provocative shortsonthe courts. “Remember?,” a Hartford Courant article dated November 2, 1930 reminisced. “The first girl basketball players who wore big baggy bloomers and black stockings, and the indignant critics who thought the world was going to the bow wows, or already had gone?” This attractive new fashion pleased the growing audiences.

Fans of girls’ basketball respected a well-played game from the beginning. Describing a contest between Windham High School Girls of Willimantic and the Naugatuck High School Girls team, The Hartford Courant reported on April 9, 1914, “The time honored theory that women are the weaker sex was given a solar plexus blow today, when a slim crowd saw two basketball teams, composed of girls, clash in Hanna’s Armory to settle the question of supremacy. When Alice and Mary happened to be both going forthe ball there was no ‘Alphonse and Gaston’ act done. On the contrary Alice just pushed Mary, and Mary fell down.” (The Windham High School team went on to claim the state championship with victories over Putnam, Plainfield, and Portland.) On May 4, 1914, The Hartford Courant published a large photo of the team with the headline, “Windham High Girls’ Basketball Team, Champions of Connecticut.” There were many high school teams that formed in those early years. Often, through newspaper announcements, they sought challenges with teams in other towns around Connecticut.

The seeds of today’s successful and popular University of Connecticut’s women’s basketball program were sown early in the winter of 1901-02 when the Connecticut Agricultural College (C.A.C.)—now the University of Connecticut—team formed. Managed by the college president’s wife, the team went undefeated for a few years. They played high schools, alumni, and professional schools such as the Anderson Gymnasium of New Haven. They insisted on playing by the men’s rules, which often intimidated their opponents and sometimes lost their chance to play a game.

That’s apparently what happened with a game scheduled against Springfield High School in February 1904. The Hartford Courant reported that the high school pulled out of the challenge because the C.A.C. refused to play by any other rules, claiming “… it would be poor policy to change the system of play so late in the day and in consequence probably incur a defeat.”

The fierce competitiveness and the foundation for what would become a championship team were established early on. In the 1920s, the Connecticut Agricultural College would hold tournaments for high-school girls’ teams and award prizes to the champions. By then, the Connecticut Aggies, as they were often called, played Connecticut schools such as Arnold College in Bridgeport and out-of-state college teams.

As the First World War approached, more women entered the workforce. Insurance and industrial companies organized and sponsored women’s basketball teams. Workers, many of them single and recruited from area high schools, benefited from the physical fitness, team camaraderie, newfound independence, and, in some instances, even fame their participation conferred. In turn, successful teams provided companies with good public relations. Fans were loyal; after the games, refreshments were served, and dancing would follow. The Travelers Girls and the Aetna Girls are the best examples of successful corporate teams that brought excitement to the world of women’s basketball.

The Travelers Girls played from 1920 through 1927. The inhouse publication The Travelers Beacon reported in 1921: “When a business girl gives her time, strength, and ability outside of office hours to carry on the strenuous work which any kind of athletics demands, for the purpose of gaining victories for the organization in which she works, she is to be admired for that spirit.” Such loyalty carried over to fans as rousing company cheers brought evening games to a close. The women wore snappy uniforms of maroon and white. By their sixth season, they had won 100 of their 116 games.

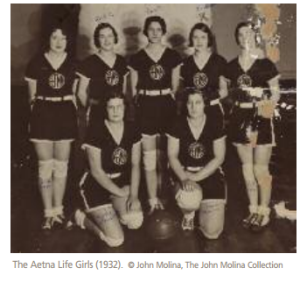

The Aetna Life Girls, nicknamed the “Crimson Wave” after their red uniforms, were coached by Adrian Brennan from 1925 through 1934. Brennan, an Aetna employee, enjoyed an unparalleled reputation among coaches and physical educators and helped make the Aetna team one of the finest women’s basketball teams in the country. For home games, they played on their own regulation basketball court in Aetna’s Bulkeley Memorial Hall, which could fit more than 1,000 people and was converted into a dance hall after the games.

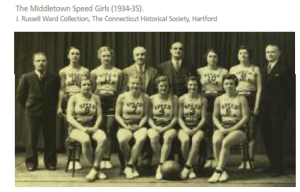

This popular team, which attracted more spectators than male teams did, competed against other insurance-league teams such as The Travelers, the Aetna Fire Girls, and the Connecticut Mutuals. Other notable teams they played were the Hartford Bloomer Girls, Insilcos of Meriden, the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, the Manchester Community Girls, Park City Girls of Bridgeport, Crofut-Knapp of South Norwalk, Hartford’s Knights of Lithuania, and the Middletown Speed Girls, among others. In 1928 the Crimson Wave triumphed at Madison Square Garden against the Metropolitan Life Girls, winning 42 to 11. Even Dr. James Naismith was impressed with their skills when he saw them compete in 1934.

Black women’s basketball teams formed in Connecticut as early as 1924. On March 2, The Hartford Courant announced a preliminary game to be played between the Basketball Team Colored Girls Reserve Hartford YWCA and the Eagle Colored Girls’ Team of Waterbury at the Hartford High School gym. In the 1940s, The Independent Social Center of Hartford started a young black girls’ basketball team called the Tigerettes. Parents and community leaders felt that good sportsmanship and citizenship would be fundamental lessons these high school girls would learn through the sport. In 1946, the junior and senior teams brought home two trophies from the state tournament held in Ansonia that year. In 1948 in New Haven, the senior team claimed the New England Negro girls’ basketball title following a 35-18 victory over the Norwalk Bomberettes. The Tigerettes also played corporate teams such as the Pratt and Whitney Girls and traveled to play the Harlem YWCA.

The Tigerettes encountered racial discrimination. Player Florence Kiser Price Wollaston recalls their coach’s telling them, “‘I don’t want any fighting; I don’t want any arguing, fussing. If you want to put all our energy to use, you put it into playing ball,’ and that’s what we did.” Coach Cora Bentley-Radcliff’s wise words kept the team unified and successful.

The Tigerettes encountered racial discrimination. Player Florence Kiser Price Wollaston recalls their coach’s telling them, “‘I don’t want any fighting; I don’t want any arguing, fussing. If you want to put all our energy to use, you put it into playing ball,’ and that’s what we did.” Coach Cora Bentley-Radcliff’s wise words kept the team unified and successful.

The barnstorming team The All American Red Heads formed in 1936 in Missouri. The team, easily identified by their flashy red, white, and blue uniforms, hair dyed red, and extraordinary athletic and entertaining abilities enticed fans when they traveled the country playing professional and semi-professional teams. These talented women competed against men’s teams using men’s rules. Gail Marks from Enfield and Cindy LaLiberte—known as “A Lass with a lot of Class”— from Thompson were selected for the team in the 1970s. They played anywhere from church basements and dance floors to large halls throughout the state, generously helped raise money for charitable causes, and served as influential role models for teenaged girls.

The modern era of women’s intercollegiate basketball was ushered in when the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) formed in 1971 to help govern all women’s collegiate athletics. The AIAW held the first national women’s college basketball tournament in 1972. That same year, Title IX was enacted. The landmark law stipulates that schools with a coeducational student body must offer equal opportunities and proportionate resources in athletics and academics. Young women now had support in addressing inequities in sports opportunities such as the practice of scheduling women’s games only after men’s games; girls’ having to use the men’s locker rooms; and nonexistent funding for equipment and uniforms. Title IX would, over the years, bring balance to these discriminatory practices as Connecticut school districts enforced compliance with the law.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) began offering championships during the 1982 collegiate season, the year the AIAW folded. Many believe that the NCAA only became interested in women’s basketball when they saw that it could produce income through national television contracts. Others feel that the NCAA was able to raise the status of women’s basketball by offering athletic scholarships, thus creating more competitive playing and highly skilled female athletes.

In the 1980s, the quality of the high-school girls’ game rose to a very competitive level. Universities offering NCAA scholarships aggressively recruited these high-school players. The championships won by the women Huskies at the University of Connecticut over the past 14 years reflect the determination, talent, and fortitude that young women basketball players in Connecticut have demonstrated since those first games in South Manchester.

In 1996, the Women’s National Basketball Association was formed. Since then, women basketball players have not only been playing for exercise and fun but to earn a living. And although the pay scale doesn’t approach that of the NBA, the league’s following is extraordinary. The Connecticut Sun’s perennially sold-out arena is a testament to that.

In the summer of 1987, five friends met at a restaurant to establish the Connecticut Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame (CWBHF) honoring individuals who have contributed to the development of women’s basketball in the state. It was the first of its kind in the nation and each year, through inductions, it honors those who have contributed to the game of women’s basketball in Connecticut.