By Jason R. Mancini

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2016

Subscribe to receive every issue!

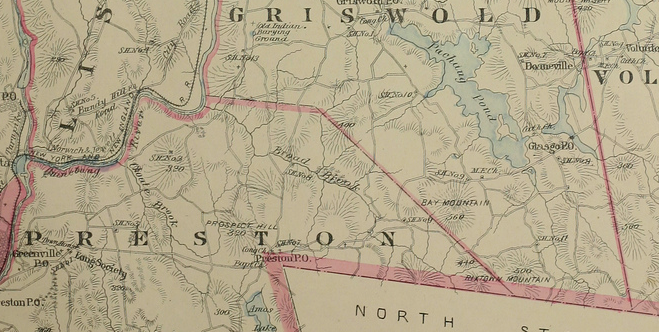

Isaac C. Glasko was a central figure in and connected to some of the most pressing racial issues and emerging economies in New England during the first half of the 19th century. A man of color, described in local histories as having both Native and African ancestry, Glasko emerged as a modern industrialist, political activist, and social anchor for a regional population of color in what would seem an unlikely place—rural Preston (later Griswold, established 1815), Connecticut. Today, a village in Griswold named Glasgo hints at the importance of the Glasko family, though a clerical misspelling and subsequent industrial activity obscures the connection between the family and the place.

Preston, located approximately 10 miles northeast of Norwich in eastern Connecticut, was connected by riverine and terrestrial routes to the Connecticut coast and to growing urban centers such as Providence, Rhode Island, and Worcester, Massachusetts. And though the population of color there was never sizable (there were 149 people of color in 1820, or about 7.9 percent of the total), the town—situated near the intersection of Pequot, Mohegan, Narragansett, and Nipmuc homelands and among the largest African/slave-holding areas in the region (New London County, Connecticut and Washington County, Rhode Island)—lay in the midst of an area that had one of the largest populations of people of color in the region.

Industrialist

It may never be known how the Glasko family came to select Preston as its new residence, but access to waterpower was likely central to the decision. In April 1806, Jacob Glasko of Northbridge, Massachusetts acquired 50 acres of land near the falls along the Pachaug River, according to Preston land records. In September his son Isaac C. Glasko of Cumberland, Rhode Island acquired a ¾-acre lot with a dwelling house bounded by a dam and the “old Iron works” nearby. This transaction included “a privilege to open said Dam…and there erect and put in a flume and draw water of [sic]of the pond…for the purpose of carrying on the blacksmith business.” He moved there with his wife Lucy Brayton Glasko, whom he had married in 1800. Their three children, Azubah (b. 1810), Isaac M. (b. 1814), and Miranda (b. 1819) were all born in Preston/Griswold, according to the Kinne Cemetery National Register Nomination prepared by historian David Ransom.

The Glaskos’ transition from the Woonsocket Falls area in Cumberland and nearby Northbridge was both timely and fortuitous. In spring 1807, one of the most powerful floods in local annals, according to Marie Louise Bonier in her 1920 book, Débuts de la Colonie Franco-Américaine, de Woonsocket, Rhode Island, destroyed the industrial corridor that was developing along the portion of the Blackstone River—an area recognized by the National Park Service as the birthplace of America’s industrial revolution (see nps.gov/blac/learn/historyculture/index.htm). The account notes, “the grist mill and the forge of Isaac Glasko, which had just recently been built and was situated near the falls, could simply not resist and was carried away like a wisp of straw. Luckily, Glasko and his wife were not in the house: before moving to the State of Connecticut, they had gone to visit their new home.” Also in that year, President Thomas Jefferson imposed the Embargo Act to force warring France and England to respect U.S. neutrality. While this sparked an economic disaster for the nascent U.S., one that would eventually lead to the War of 1812, it was a period of great opportunity for the Glasko family.

The Glaskos’ transition from the Woonsocket Falls area in Cumberland and nearby Northbridge was both timely and fortuitous. In spring 1807, one of the most powerful floods in local annals, according to Marie Louise Bonier in her 1920 book, Débuts de la Colonie Franco-Américaine, de Woonsocket, Rhode Island, destroyed the industrial corridor that was developing along the portion of the Blackstone River—an area recognized by the National Park Service as the birthplace of America’s industrial revolution (see nps.gov/blac/learn/historyculture/index.htm). The account notes, “the grist mill and the forge of Isaac Glasko, which had just recently been built and was situated near the falls, could simply not resist and was carried away like a wisp of straw. Luckily, Glasko and his wife were not in the house: before moving to the State of Connecticut, they had gone to visit their new home.” Also in that year, President Thomas Jefferson imposed the Embargo Act to force warring France and England to respect U.S. neutrality. While this sparked an economic disaster for the nascent U.S., one that would eventually lead to the War of 1812, it was a period of great opportunity for the Glasko family.

In March 1807 Jacob gave his sons Isaac and George each a third of his 50-acre property in Preston. In July 1807 Isaac and George together purchased an additional acre of land that featured a house, gristmill, and dam. According to Daniel L. Phillips’s 1929 Griswold–A History, Isaac Glasko “had a genius in forging iron and steel, and in tempering tools.” Glasko constructed a water-powered trip-hammer forge, and with this technological advantage “his shop became famous for the farming and carpentry tools which he manufactured.” With this innovation, the Glaskos (with Isaac at the helm) formed a very profitable mill seat in a mostly white town. During his first 20 years at this location, Isaac Glasko centralized control over the growth and expansion of his blacksmithing operation, acquiring a total of 70 acres of land that included four homes and various mills.

Though no known archive of Glasko’s business records exists, some fragments including newspaper advertisements across the region reveal that his success may have been tied not just to “superior quality” tools but to his ability to adapt to changing market needs. The first ads for his blacksmith shop (found in the Windham Herald, 1810, and the Providence Patriot, 1819) promoted agricultural tools such as scythes (1810 – 1823), then axes (1828)—likely for clearing new lands—ox carts and wagons for field and marsh access and possibly for migrations out of New England or general westward movement (as seen in the New London Gazette, 1838). Receipts for whaling implements in the archives of Mystic Seaport (1836 – 1850s) and in Connecticut Agricultural Society Records (1854, 1856) show his move into the maritime market.

Social Anchor and Mentor

Isaac and Lucy and their family were part of a network of inter-related families that included his brother George and his wife (probably Charity; the only known reference to his wife’s name is from cemetery records in Putnam) and their children Elsa (b. 1812) and Henry B. (b. 1814). Though George was part of the original Glasko enterprise, land, court, and census records indicate that after a series of lawsuits from 1813 to 1817 George and his family left Griswold and relocated to the towns of Killingly and Thompson in northeastern Connecticut between 1817 and 1840.

Other members of the Brayton family from the Smithfield, Rhode Island area also migrated to southeastern Connecticut. Moses Brayton, who was likely a brother or uncle of Isaac’s wife, first appeared with his family in the Griswold census in 1820. Pardon P. Brayton, Isaac’s brother-in-law, appeared in that year in Groton, having married Mary George of Mashantucket and relocated to the Indian reservation where they raised their three children, Pardon Jr. (a blacksmith), Lucy Ann, and Charles (a whaler) there.

Griswold seemed to become a center for blacksmithing, providing opportunity and stable form of employment for people of color. A review of historical data available from Barbara W. Brown and James M. Rose’s Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut (New London County Historical Society, 2001) and from the People of Color Database at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, reveal that more than four-fifths (23) of the known blacksmiths of color from eastern Connecticut and adjacent areas of Rhode Island lived and/or apprenticed in Griswold or Preston, including Glasko’s son, Isaac M. Phillips indicates that Glasko “constantly employed eight or ten men.”

Many of the men of color identified as blacksmiths who resided in Griswold also had social and economic connections in New London, Putnam, Voluntown, Plainfield, Lisbon, Canterbury, Smithfield (Rhode Island), and Uxbridge (Massachusetts). While much of the production of tools and equipment was centered in Griswold, Glasko may have been involved in creating satellite shops. In one case, between late 1844 and early 1848, Isaac appears in records for the Steamboat Hotel on Bank Street, as noted by proprietors William and J. L. Bacon in New London. He was almost certainly setting up a blacksmith shop for his nephew Pardon Brayton. Brayton appears next to Glasko in the 1840 Griswold census and is listed as having his own shop in the whaling center of New London in 1850. This correlates well with Phillips’s assertions that “when the whaling industry was at its height, he made a specialty of whaling implements; and Glasko’s harpoons, lances, spades, and mincing knives were well and favorably known in all New England ports.”

Glasko’s mentorship also extended to his son Isaac M. Glasko. The younger Glasko won awards for his whaling implements from the Connecticut Agricultural Society in 1854 and again in 1856.

Political Activist

May 20, 1823 marks the beginning of Glasko’s civil rights activism. It was then that the New London Gazette reported that Glasko, his close friend Pero Moody, and others collaborated to submit a petition to the Connecticut General Assembly for exemption from taxation because they were denied voting rights. The petition “was read and referred to a select Committee…setting forth the grievances resulting from their exclusion from all places of honor, trust, or profit and praying exemption of their persons and property from all taxation, they not being in any way represented.”

The grievance followed closely after the dissolution of an advertised partnership with Thaddeus Prentice, a white resident of Griswold. April 23, 30, and May 7 ads in the Norwich Courier announced that, “all persons indebted to said firm, are hereby notified that payment must be made to the subscriber [Glasko], and to no other person whatsoever.” Glasko and Prentice pursued one another in court over an accounting dispute. Glasko initiated the action on April 7, a countersuit by Prentice ensued, and the dispute was resolved in Prentice’s favor on May 29. Glasko was ordered to pay $700 in damages.

The 1823 petition by Glasko and others illustrates the frustration people of color experienced while dealing with discriminatory and predatory practices of some of their white neighbors. More than half of the towns in New London County, including Preston, omitted families of color (land-owning or not) from the U.S. Census in 1810. Their exclusion from the census compromised their standing in the body politic by limiting their visibility, representation, and voice. In spite of socio-economic successes, little headway was made with securing civil rights. Voting, which was restricted in Connecticut to men who held property and who had been accepted as qualified voters, was limited by statute to white men in 1814 (and in the state constitution of 1818).

As more people of color achieved freedom from slavery or indentured service, got jobs, and became property owners, it appears that there was tremendous resistance to their new autonomy and growing success in the early republic, especially as manufacturing and industrialization were creating wealth. For Isaac Glasko, success did not go unnoticed. “So great was his success that jealousy was aroused. Some of his rich white customers began to tell that ‘that nigger’ was living in as good style as themselves, and the Glaskos were made to feel race prejudice so bitterly that both father and son [Isaac C. and either Jacob or Isaac M.] were known to say that they gladly would be skinned alive if they could come out white,” asserted Phillips–albeit a century after the fact and without attribution.

In anticipation of a judgment against him in the Prentice case, Glasko began to market, promote, and distribute his “superior” scythes outside the local area. Beginning May 15, 1823, his scythes were advertised in Middletown, Connecticut and Providence, Rhode Island newspapers. Conducting business away from his neighbors may have provided relief of sorts. Before this, Glasko had been involved in nine court cases (5 as plaintiff, 4 as defendant); after his grievance, Glasko was not involved in another court case for 17 years.

By August 1827 Glasko had become one of two authorized subscription sales agents in Connecticut for Freedom’s Journal, the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States “devoted to the improvement of the coloured population.” The journal, published weekly in New York City from 1827 to 1829, provided valuable information to subscribers about topics such as the history of slavery, “colored” schools, family government, meetings, atrocities committed against people of color, news from around the nation, international news, poetry, an almanac, varieties, and ads.

On February 29 and March 7, a two-part editorial about the African Colonization Society appeared in Freedom’s Journal. Coincidentally or not, only two weeks later, on March 26, 1828 and again on April 2 and 9, Glasko advertised his intent to sell his business and property in the local Norwich Courier. The advertisement provides a sense of the extent of his business and real estate holdings, stating that the property was “known by the name of Glasko’s establishment, and is of the description following: a blacksmith shop with seven fires, with bellows’ by water power, two hammers, two grindstones, all by water power, a finishing shop for scythes and other work, … all under the same roof—and is in all respects one of the best establishments of the kind in the New England States, and one that stands in as high repute as any other .…” These “works occupy the best water privilege on the Pachaug River.” The advertisement also offered for sale Glasko’s four dwelling houses, “one of them two stories high” and “entirely new built of the best materials, and in the most convenient style” and 70 acres of “good land, under good improvement.” The ad provides a sense of scale, of property and wealth, from which Glasko might have walked away.

But Glasko never sold his property. He continued to operate his establishment even as the tone of race relations had turned decidedly negative in southeastern Connecticut, fueled in part by Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion in Virginia. By the early 1830s, students who attended Prudence Crandall’s school for “young ladies and Misses of color” (including Glasko’s niece Elsie and Sarah Harris, future wife of blacksmith George Fayerweather) in nearby Canterbury, Connecticut actually met with violent resistance. This school, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was attacked by a mob of white protesters and subsequently closed, in 1834.

After all of this, Glasko and his son continued to operate the forge for what would be another 30 years. Glasko died in 1861 while visiting his daughter in Norwich. The timing of his death coincided with the outbreak of the Civil War and the expansion of Northern manufacturing. By 1866, according to Griswold municipal historian Lillian Cathcart, Glasko’s property and water privilege had been adapted for use by the Griswold Paper Company. After the failure of this company, the mill was reopened as the Glasko Yarn Mill Company. As the company expanded, houses, a general store, and a post office were built for workers. An error by the post office resulted in a permanent name change: Glasgo.

Isaac C. Glasko—the blacksmith, the civil rights activist, the community leader—was a hero for the region’s population of color. This narrative of his life has been forged from a broad array of historical fragments, most of which are noted herein. More will be uncovered and with that, his life—and ours—enriched.

Jason R. Mancini was executive director of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. He wrote “New London’s Indian Mariners” in the Summer 2009 issue of Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

Conversation at Noon: Industry, Activism & Community in 19th-Century Connecticut.

A discussion about social activism and exploration of the world of early political activist and community leader Isaac Glasko with Jason Mancini. Connecticut’s Old State House, 800 Main Street, Hartford. ctoldstatehouse.org