(c) Connecticut Explored, Winter 2014-2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Throughout American history, some wars have been deemed necessary and right to pursue and others considered tangential to the interests of the United States. The Great War was among the latter, at least initially. From 1914 to 1917—when the Allied and Central powers were engaged in combat but before the United States had entered the war— Americans hotly debated the issue of U.S. military involvement. Participation was an unpopular idea, so much so that in 1915 the mother’s lament “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to be a Soldier” was a huge hit song, sold as sheet music, performed on stage, and even parodied. In 1916 President Woodrow Wilson was re-elected under the slogan, “He Kept Us Out of War.” Nevertheless, during this contentious time many Americans were involved in war relief.

In “Greenwich Faces the Great War,” on view through March 22, 2015, Greenwich Historical Society explores the ways in which residents—some prominent and many not—supported the war effort both before and after the U.S. entered the conflict. (See Explore!, page 25.)

Before the U.S. entered the war in 1917, many women in Greenwich, as elsewhere in the United States, publicly supported refugee relief and related charities, their anti- or pro-war beliefs notwithstanding. Once the United States formally joined the conflict, national leaders announced that the time for debate was over. The Espionage Act of 1917 curtailed expressions of anti-war speech, and the federal government formed the Committee on Public Information to encourage all Americans to get squarely behind the war effort. The experiences of individual women and girls in Greenwich illustrate the political ramifications of even the most commonplace activities during World War I.

Through the committee’s mass-marketing campaign and volunteer initiatives, women were reminded of their patriotic duty to encourage male relatives and friends to enlist, to see to it that all family members, including children, contributed to the war effort, to do their part at home and in the community, and to bolster spirits by remaining strong. Women were asked to preserve and conserve food, to conserve fuel, to buy war bonds rather than non-essential consumer goods, and to participate in war-related charities. For some, participation in support activities during World War I was tied to a sense of patriotism so strong it would never be rivaled or topped, not even during World War II. As Riverside neighborhood resident Marjorie Jones George, who was a military and ambulance driver in Greenwich, later recalled in an interview for the Greenwich Library Oral History Project, “Everybody was very, very patriotic. Nothing like the other wars since. I sold Liberty Bonds. Everyone rolled bandages and knitted. There was great patriotism.”

Many women took on jobs traditionally filled by men, running their husbands’ businesses and working as military drivers/auto mechanics, farmers, and waiters. Other women, including Jutta J. Anderson, Florence L. Dixon, and seven other women from Greenwich, served as nurses in the U.S. Army, according to Service Records: Connecticut Men and Women in the Armed Forces of the United StatesDuring World War, 1917-1920 (Office of the Adjunct General, State Armory, Hartford, Connecticut; 1941).

Grace Gallatin Seton numbered among the Greenwich women who received accolades for her war-time service. Seton, whose husband was the famous nature writer Ernest Thompson Seton, founded Le Bien-Être du Blessé (Welfare of the Injured) Women’s Motor Unit in 1916. This all-female transport service moved people and goods in the war zone. Seton described it in the Journal of National Institute of Social Science (J. J. Little & Ives Company, 1920):

The little fleet of eight Ford Camionettes . . . organized and operated entirely by women, traveled thousands of miles: carried tons of food and comforts to the wounded—during the first months to the Emergency and Field, and, later, to the Base Hospitals; kept open the doors of several Hospitals by its service, when the break-down of the French Transport System was at its worse; undoubtedly saved hundreds, and alleviated the suffering of thousands, of French soldiers, and of many Americans, wounded in the Great War.

By her nature, Seton was a successful organizer and fundraiser. With her husband she had founded the group later called the Camp Fire Girls in 1910, and she was a leader of the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association during the 1910s. Seton lived in England from 1912 to 1914, which may have sparked her direct involvement in the motor unit. She was awarded medals from England and France for this effort.

“A Group of the Entrepôt des Dons of the Bien, 1918-1919.” Grace Gallatin Seton of Greenwich, second from left, won accolades for her war-time work, including her founding of Le Bien-Être du Blessé (Welfare of the Injured) Women’s Motor Unit in 1916.

This particular project illustrates some of the primary and secondary motivations in play. Seton and her supporters were typical of those Americans, particularly in artistic and literary circles, whose affinity for France made them especially sensitive to the war’s threat to that country’s people, art treasures, and land. Seton was also one of a number of nationally recognized suffragette leaders from Greenwich who realized that women’s participation in the war effort could also advance the “votes for women” campaign. In fact, Seton’s motor unit was sponsored by the New York Women’s City Club, an organization founded by suffragettes in 1915.

Others in Greenwich’s suffrage movement turned their attention to maximizing agricultural and food production. Rosemary Hall headmistress Caroline Ruutz-Rees, who led the Connecticut Division of the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, and philanthropist, feminist, and renowned art collector Louisine Havemeyer publicly championed the Woman’s Land Army of America. The WLA was modeled on the British Women’s Land Army. In both programs, women took the place of men who left farm fields to fight on battlefields. Havemeyer founded the Greenwich Canning Kitchen, a model program for preserving home-garden bounty. Havemeyer had co-founded the National Women’s Party with Alice Paul in 1913; she provided financial support to the cause of women’s suffrage and spoke, marched, and demonstrated for the cause. Ruutz-Rees served on the executive board of the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association, was active in the Greenwich Equal Franchise League, and organized the National Junior Suffrage Corps. She had her students at Rosemary Hall cultivate potato fields and a war garden while helping with landscape maintenance on the school’s campus.

“Doing Their Useful and Sensible Bit.” Rosemary Hall students ready to work their potato fields, c. 1918. Choate Rosemary Hall Archives

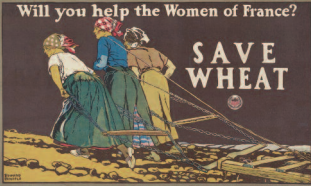

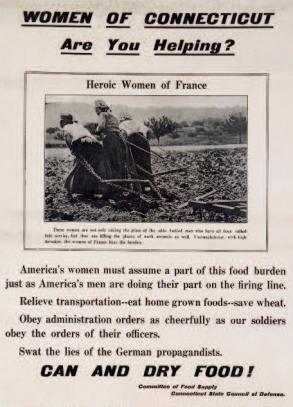

Women like Ruutz-Rees and Havemeyer appreciated the interconnectedness of food and politics. As early as 1914, America’s leaders were concerned about the negative impact the war would have on food supplies in Europe. Once the United States had entered the conflict, the urgency became even greater as American men left their farms to fight. Americans were encouraged to produce, preserve, and conserve food stuffs. They tended home and community war gardens (World War I versions of victory gardens) and voluntarily restricted the amount of wheat products, meat, sugar, and fats they consumed. Devoted gardeners, canners, and cooks adopted “kitchen patriotism,” a phrase used in propaganda, advertisements, and elsewhere during the era to describe these efforts.

The Woman’s Land Army was one of many war-related initiatives that helped break down gender barriers as women assumed the heavy farm labor typically reserved for men. With a training camp in nearby Bedford, New York, the Woman’s Land Army began working in farm fields in Greenwich, such as Sabine Farms as Joan Fisher Faulkner recalled in her Greenwich Library Oral History Project interview, and surrounding areas. As Elaine F. Weiss notes in Fruits of Victory: the Woman’s Land Army in the Great War (Potomac Books, 2008), the young women who participated received two dollars per day for eight hours’ labor. According to Weiss, these “Farmerettes” were often college students and socialites and viewed tending and harvesting crops wearing overalls and trousers as a novel patriotic adventure. In contrast, female members of farming families generally found the work more routine than exciting.

The Greenwich Canning Kitchen was established in 1917 as a way to contribute to food coffers. The goal was to preserve the produce of war gardens and small farms that might otherwise go to waste. Residents brought in produce to be processed for their own use or for consumption by troops or civilians in need. This program operated out of a storefront on Railroad Avenue. Mary Curcio was one of many teenagers who worked putting up preserves and canned goods as part of the effort. She told of her labor for the Greenwich Library Oral History Project:

We would get vegetables in burlap bags. People had huge gardens in those days; many of these wealthy people that lived around Cos Cob and Greenwich, Stanwich Road and all that, would send in all these vegetables to be canned, and they were tremendous. It would take days. It would take a whole day just to clean a bag of beans, and then you’ve got to wash them and blanch them and put them in jars, and then put them in their hot bath. And you’ve got to remember we didn’t have any electric stoves or gas stoves. … You know, dip them down into the water, you know. But the trick of the whole thing was that you could not let that water stop boiling. It had to keep going all the time. So, you see you had to keep on stoking the fire all the time. I don’t know how in the world we did it but anyway, we did it. And I remember too, making hundreds, not one or two dozen, but hundreds and hundreds of bottles of jelly.

“Women of Connecticut, Are You Helping?” Committee

of Food Supply, Connecticut State Council of Defense, c. 1917.

Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut

Similarly, Constant Holley MacRae (whose family home was later preserved by the Greenwich Historical Society) pursued her serious interest in food preservation as both an individual homemaker and as a member of women’s clubs during the war. In June 1917 she attended a week-long canning course held at the University of Connecticut in Storrs, and she and her twin daughters Clarissa and Constant joined the Mother-Daughter Canning Club of Greenwich. They were part of a phenomenon by which women leveraged and redirected the female club and committee system to take up war-related causes. According to “Waterless Food in Two Suitcases Appeases Appetites of 75 Women,” (New York Evening Telegram, January 21, 1918) MacRae was among the Greenwich Garden Club members who served a demonstration meal to other women’s club members, food experts, and government officials in Washington, D.C. Their purpose was to show how dehydrated “rations” could make it possible for all American service personnel, no matter where they were stationed, to enjoy a tasty Thanksgiving feast. Since the Civil War, leaders had used the observance of Thanksgiving to boost the morale of American troops, and during the Great War years, partaking of a Thanksgiving meal was a meaningful ritual for military men.

As was true of women across the nation, Greenwich women and girls immersed themselves in American Red Cross activities. Louise Van Dyke Brown, Alexandra Spann, and others recalled (as part of the Greenwich Library Oral History Project) gathering at the Greenwich YMCA and other locations to fashion surgical dressings and to knit socks, mufflers, helmet liners, and other items for soldiers. Annie Louise Brush wrote of this work in her diaries, which were recently added to the collection of the Greenwich Historical Society. On April 21, 1918, she recorded that the death of Colonel Raynal Bolling from Greenwich had been verified and that “Mrs. Bolling is from all I hear a herione [sic], when she knew that her husband was missing she controlled herself and had the people come to her house as usual for dressings and worked with them.”

The Red Cross had been founded in the 19th century as an apolitical, international organization dedicated to providing humanitarian and medical assistance to all war combatants. But once the United States declared war, President Wilson made the organization an adjunct of the United States Army and directed it to aid only the Allied Powers. The American Red Cross delivered medical care at military hospitals, operated ambulance services in the war zone, provided relief to refugees, and coordinated the efforts of all American relief agencies.

A woman’s involvement in the American Red Cross became a litmus test for a woman’s patriotism, as Rose Pastor Stokes, a some-time Stamford resident with strong ties to Greenwich’s Socialist community, experienced. As Kathleen Kennedy notes in Disloyal Mothers and Scurrilous Citizens: Women and Subversion During World War I (Indiana University Press, 1999), Stokes’s attitude towards the Red Cross was a point of contention during her initial trial. When she was tried in federal court under the Espionage Act for expressing opinions considered anti-war, prosecutors pointed out that she had been a supporter of the organization before, but not after, the American declaration of war in 1917.

According to the news report “Mrs. Stokes Denies Assailing Red Cross” (The New York Times, May 22, 1918) Stokes testified that she had not, as accused, called the Red Cross “profiteering camouflage” and in fact had contributed 50 dollars to the organization in 1917, while a witness to the speech that had gotten Stokes in trouble recalled her having stated that “she had stopped knitting and doing Red Cross work when she was reminded that German and Austrian boys were being killed in this war.” Stokes was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison, but she successfully appealed.

“The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” famously marked the ceasefire on the western front in Europe. Once Germany had signed the Armistice, the Allied Powers celebrated. In Greenwich as elsewhere in America, bells rang, whistles blew, and people took to the streets in celebration. At the very end of 1918, Americans and other Allied troops marched into Germany. President Wilson arrived in Paris to attend the peace conference that resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919.

“Hoeing potatoes—not as easy as it looks.” 1918. Scrapbook of farmerettes, Sabine Farms, Greenwich. Greenwich Historical Society

Both far from and near to home, Greenwich women supported the war effort in meaningful ways. They served as nurses, drivers, farmers, and Red Cross workers, assuming jobs generally reserved for males in response to a labor shortage. While anti-suffragettes and suffragettes alike took part in food and fuel conservation, fund-raising for relief charities, and other activities, suffragists particularly benefited from women’s war record. Their contributions were widely taken as proof that women had shown their mettle and were deserving of the vote. This attitude was particularly strong in Greenwich, the home of some of the state suffrage movement’s most high-profile leaders. Women’s passionate service during the war inspired the previously reluctant President Wilson to finally agree to women’s suffrage. As he recognized in a speech to Congress in 1918, “we have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” By late 1920, a majority of states (including Connecticut, which only signed on after a majority of states had assured adoption) had ratified the 19th Amendment, which banned any federal restrictions on women’s right to vote. Women’s war-time experiences set the stage for the arrival of the Modern Woman during the 1920s.

“Off for Work! The Original Unit, May 1, 1918.” Scrapbook of farmerettes, Sabine Farms, Greenwich. Greenwich Historical Society

Kathleen Eagen Johnson is the guest curator of “Greenwich Faces the Great War.” She is a freelance museum consultant and writer at HistoryConsulting.com.