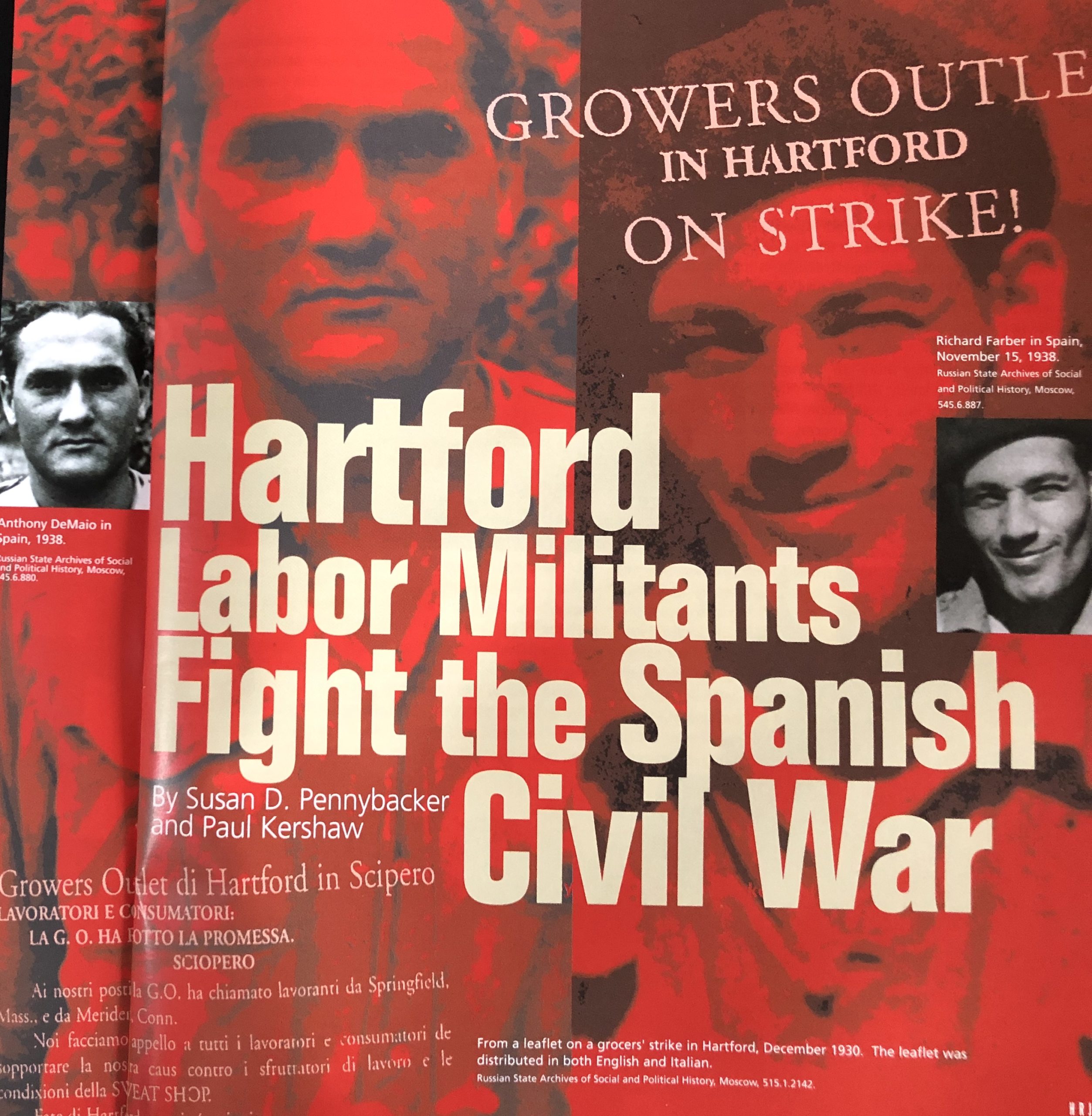

left: Anthony DeMaio in Spain, 1938; right: Richard Farber in Spain, November 15, 1938. Russian State Archives of Social and Political History, Moscow

By Susan D. Pennybacker and Paul Kershaw

(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In September 1937, the Hartford Woman’s Club was the scene of a fundraiser for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. The 300 persons in attendance were not there to commemorate the War Between the States, but to listen to speakers Thomas R. Molloy, president of the United Auto Workers of Hartford (Local 348) and a leading CIO organizer and Communist supporter, and Hartford attorney Harold Strauss. Three Lincoln Brigade veterans from Boston also spoke. They cheered the nearly 3,000 American men and women, black and white, who were fighting for the fledgling Spanish Republic in a war between “democracy and fascism.” Molloy “identified the struggle of the Loyalists with those of organized labor throughout the world.” Strauss praised their efforts and condemned a Hartford ordinance “banning distribution of handbills on the streets” that constrained labor activism and violated the constitutional right to free speech. Over $100 was collected to aid wounded Brigade volunteers, and a support group was launched.[1]

By the 1930s, antifascism was an international cause célèbre. The declaration of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931 occasioned waves of political violence between opponents and supporters of democracy that repeatedly threatened Spain’s stability and eventually cost the lives of half a million people. The rise of fascism in Italy, global economic depression, the Nazi revolution in Germany, and zig-zags in Soviet policy, all influenced the tragic fate of Spain. When the elected government was overthrown in a coup led by General Francisco Franco in July 1936, the Left and workers’ parties organized a Republican army that recruited volunteers from many countries. The Soviet Union was centrally involved through national and local Communist parties; more than 40,000 international volunteers went to Spain. The Connecticut regional Communist Party (CP) of roughly 600 members sent the call out to aid in the fighting.

At the Hartford Woman’s Club meeting, a letter was read from Richard Farber of 98 Enfield Street in north Hartford, identified as the 1934 Communist candidate for Connecticut attorney general. Farber, a 32-year-old sheet metal worker, lathe operator, and asbestos worker in the building trades, had arrived safely in Spain. It was also announced that a second Hartford volunteer, Anthony DeMaio, of 838 New Britain Avenue, a 23-year-old boilermaker and electrical engineer, had attained the rank of personnel officer in his unit after serving on the front. From their first arrival in Spain in January 1937, the American units, known collectively as the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade” fought alongside troops from across Spain, Europe, and Latin America. Mussolini’s army and German Luftwaffe aerial bombings aided the Franco side. By April 1938, the Republican-controlled region had been cut in two. A farewell parade in Barcelona in October 1938 signaled the departure of the American volunteers, more than a third of whom had perished in battle. They left amid deep political division among the Republican forces. Franco’s army entered Barcelona in early 1939, signaling the war’s closing and fascism’s triumph.

Anthony DeMaio and Richard Farber: Labor Militants and Brigadistas

Most of the American volunteers in Spain came from America’s largest cities, 18 percent were from New York alone. They were typically in their mid-20s and most were single men, though 60 women served. Most were immigrants or the children of immigrants. A third were Jewish; 80 were African American. While a majority, like Farber and DeMaio, were Communist Party members, at least a quarter were political independents. Many had previous Socialist Party and militant trade union backgrounds.[2] While only a dozen Connecticut recruits fought in the Lincoln Brigade, Farber (1906 – 1985) and DeMaio (1914 – 1999) were in many other respects fully representative of their era, their region, and their city.

Richard Farber came from an immigrant Lithuanian Jewish family. His father, William, whom he described in a questionnaire filed in Spain, as an “Independent Democrat, New Deal” was a dry goods peddler who became the superintendent of the Garden Street Synagogue and Beth Madresh Hagodol Synagogue on Greenfield Street. His brother, Louis, a plumber at G. Fox and Co.; his mother, Esther; and his sister, Ruth, a nurse, all shared the house on Enfield Street. Farber had completed two years of high school and his work in the labor movement and the Left rendered him an avid reader of Marxist and Communist works; he also spoke Yiddish.[3]

Anthony DeMaio’s parents were southern Italians who met in Hartford. His father, Donato was from Abruzzi and his mother, Serephine Rucci, came from Naples. Donato DeMaio immigrated in 1899 to join his brothers, a laborer and a baker who lived at 178 Front Street. Donato, soon “Daniel,” lived nearby at 19 Mechanic Street. Anthony was one of nine boys, three of whom died of influenza. His older brother, Ernie, recounted life at home:

My earliest recollections are very political recollections — heated discussions that used to take place in our kitchen… I recall being awakened at night by what I later learned was gunfire. It seems that in the heated discussion among the Anarchists and Socialists and [during]the rising Bolshevik Movement in Russia, they were trying to resolve some doctrinal differences… We went through those days, cops and robbers, cowboys and Indians, Bolsheviks and Mensheviks… And the stories that the papers [ran], showing Bolsheviks in those days all hairy, a bomb in one hand, a dagger in the other. Unbelievable, the cartoons that they used to make in those days…. So, you see, I come from the kind of working class background, interest in social emancipation, without being too clear as to what the hell it was all about.”[4]

Donato DeMaio, a sometimes chauffeur, construction worker, and ball-bearing factory worker, was arrested with his brother-in-law in the Palmer Raids. These federal sweeps of labor militants, most often immigrants, were named for the U.S. Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer. The federal authorities nabbed more than a dozen Hartford workers on January 2, 1920. Though the raids were later deemed illegal, many of those arrested were deported and others held without trial. Anthony’s uncle Tony, who had been a trade union organizer with the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies) received a two-year prison sentence and Donato, six-months. Ernie recalled him stocking the family larder with staples before he left for jail. Anthony, Ernie, and two of their brothers lived in an orphans’ residence for a time after their mother’s death from tuberculosis in 1921. Ernie believed that his father’s arrest “broke her health.” She had been active as a suffragette and Ernie described her role in the community: “Because she came here at the age of four, she acted as an interpreter, and consequently, was sort of a bridge between the old Whites, Anglo-Saxons, Protestants… and the newcomers who were mainly Catholics from Italy.”[5]

Later, the DeMaio family was active in support of the campaign to free fellow immigrant workers, Sacco and Vanzetti, anarchists executed for murder in Massachusetts in 1927. As a result, Donato was blacklisted in the construction trades. The Italian community was hardly unified in its politics. Anthony recalled being ostracized in Italian neighborhoods in Hartford for his support for Ethiopia when the Italians invaded North Africa in 1935. Many immigrant family women divested themselves of gold jewelry so it could be melted down to assist in the Italian fascist war effort.[6] Ernie, however, also described the Italian community’s common experience: “We were often called white niggers, Guineas, WOPs, Grease balls… we were discriminated against.”[7]

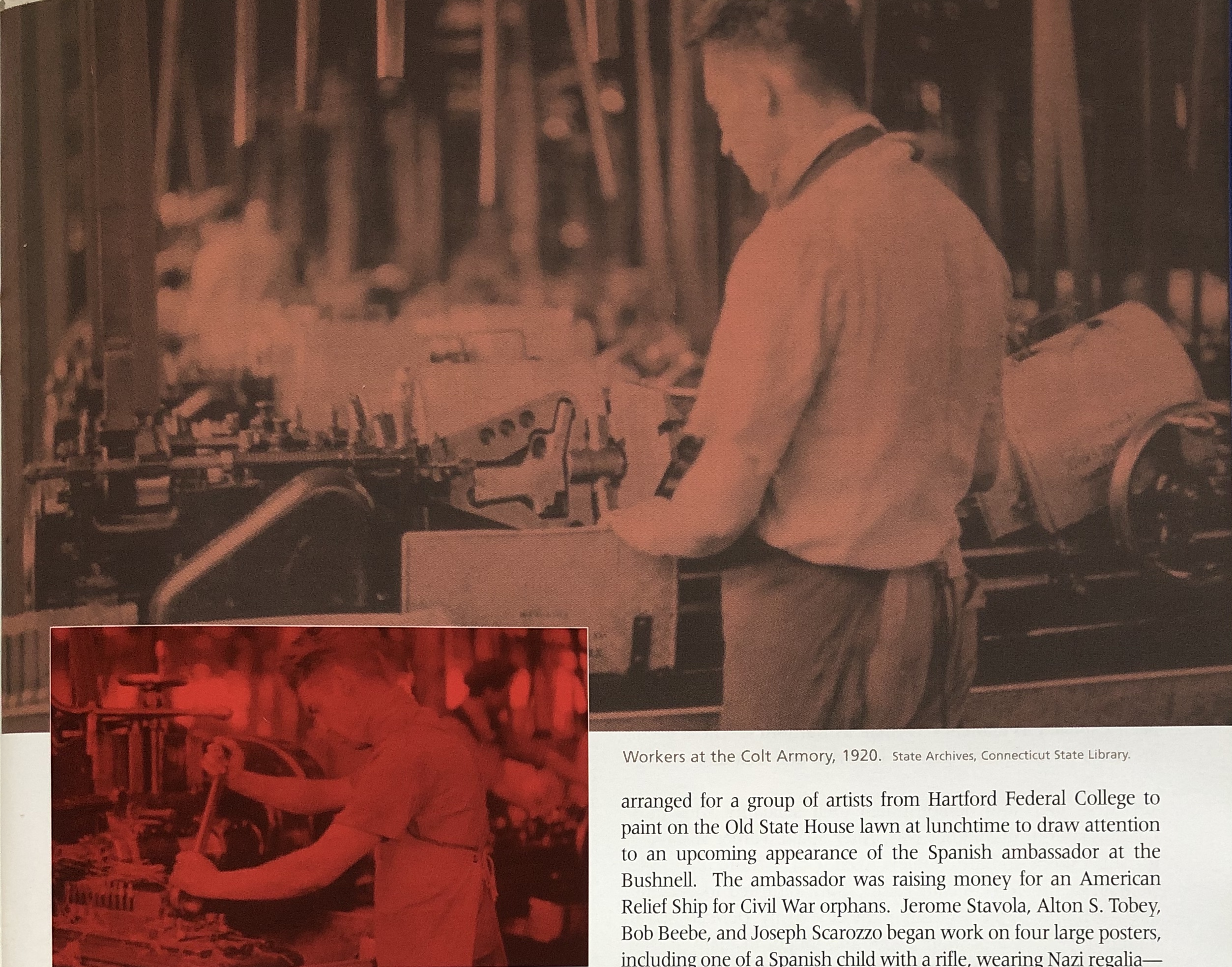

Richard Farber and Anthony DeMaio were Communist organizers and factory militants. Farber worked in Hartford as an errand boy, Aetna clerk, and master mechanic. He was a member of the Socialist Party as well as the American Federation of Labor (AFL) asbestos workers’ union from 1928-29. He joined the Communist Party in 1933 and was active in the “Red” union movement and the International Labor Defense, the CP’s legal defense arm. He undertook organizing unemployed workers from 1933 – 1934, and was involved in the 1934 strike at Pratt and Whitney Aircraft in East Hartford. He organized at Colt Firearms, which struck in 1935. Farber was arrested twice before he left for Spain — at least once for disorderly conduct in an episode that he recalled as a violation of the right to leaflet. He was tried in the courts in Hartford with two other Communists but the charges were dismissed. Farber ran for public office four times on the Communist ticket — first in 1934 for state’s attorney general; twice in 1935 and 1937 for alderman-at-large; and in 1936 for Congress.[8] From 1934 – 1936, he was a Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) organizer, and from 1935 – 1936 he was a Party organizer in Waterbury.

Anthony DeMaio joined the Young Communists and the YMCA in Hartford and completed high school. In 1932, he witnessed the war in China during a four-year stint in the navy. He joined the Communist Party in 1935, became a CIO organizer like his brother, and worked in Bridgeport as a boilermaker for more than two years. Meanwhile, brother Ernie founded the United Electrical and Radio Workers Union (UE) in 1936, the largest industrial union in Connecticut to which both brothers became deeply committed. Anthony also worked in New Jersey, where he was secretary of his union local in Hudson County. Their brother, Albert also served in Spain.

The Left and Labor in Connecticut

Farber’s and DeMaio’s radical formations lay in the deep inroads that U.S. labor activism, combined with European-influenced doctrinal politics, had made in their homes, city, and state by the 1930s, where the Communists vied for leadership among several labor organizations. The Socialists were especially strong in Bridgeport where they won the mayor’s office with the election of Jasper McLevy in 1933. AFL “craft unionism” had a history in the region, and there were six branches of the Jewish Workmen’s Circle in Hartford. But the Communists had only a few dozen Hartford members in a city with a strong paternalist company tradition and a repressive order enhanced by the presence of the capitol and the state and local authorities. There were over 350 factories in Hartford by 1930, employing 25,000 workers and a majority of the city’s population was dependent upon factory labor. But Hartford was known as an “open shop” city in which employers ruthlessly fought labor organizers with spies, firings and blacklists. An Underwood Typewriter executive, president of the local Manufacturers Association in the 1930s, was an avowed admirer of Mussolini.[9]

Still, Hartford drew demonstrators confronting the state government, and militants who attempted to organize manufacturing workers in armaments, the typewriter firms, and the metal trades. In 1926 worker solidarity brought crowds to north Hartford’s Schuetzen Park for a State Labor Picnic including: Communists who organized under the banner of the Workers Party, the Scandinavian Society, the Lithuanian Literary Society, the Finnish Workers’ Club, and the Freiheit Singing Society of New Haven. Five hundred automobiles from Connecticut and Massachusetts lined the Hartford streets. A Passaic, New Jersey strike leader and the Socialist leader, Mother Bloor, addressed crowds in Keney Park. By the late 1920s, there were also ex-Communist factions in the region, including a few Trotskyist sympathizers and a large group of followers of Jay Lovestone, the leader of a breakaway Communist Party faction. By 1928, there were over 500 Connecticut Communists in the building, metal and rubber trades, as well as women who worked at home. Within three years, 10 percent of the state CP membership had moved to the USSR, fleeing unemployment and repression, though some returned disillusioned.

Colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company (looking north), 1936. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

In 1930 labor activists working at Colt published the Workers’ Gun with a circulation of 1,000 copies. The Underwood Roller and The Royal Fighter circulated in the typewriter firms. The July 1930 Royal Fighter read:

We workers in this shop have to work under very bad conditions, long hours and for low pay. The average wages of us workers is seldom over 40-45 cents an hour and certainly this is not enough to enable us to get along even half way decently… The Royal Fighter is being published by us workers and by the Communist Party in order to Organize the workers in our shop to fight for better conditions. Against the power of the bosses we will organize the workers and fight unitedly.[10]

The electoral contests mounted by the Communist Party were run under slogans like: “Workers of Connecticut, Vote Communist! Fight Against Hunger and Unemployment! Fight for Unemployment Relief.” In 1930 the CP successfully received the 6,500 signatures necessary to remain on the state electoral ballot. In January 1931, the CP unemployment campaign in Hartford collected 4,000 signatures of support. Several hunger marches, like those mounted in the United Kingdom in these Depression years, passed through Connecticut in the early 1930s. A 1931 Connecticut hunger march was comprised mostly of foreign-born workers, including 20 Russians and 18 Finns. Of the 135 who marched, six were African Americans. In 1932 the CP election campaigns had a special focus on unfair evictions of poor tenants and rallies were held at Pratt and Whitney Aircraft. Ten thousand pieces of literature were sold statewide and one of the national candidates spoke on Hartford’s radio station WDRC.

The Hartford CP branch operated from an office at 2003 Main Street in the Labor Education Alliance building from 1928 – 1934. The leadership of the Hartford branch in the mid-1930s included African American Billy Taylor from Washington D.C., and Max Feldman of 227 Barbour Street. Fully 85 percent of Connecticut CP members in 1931 were immigrants and many were Jews. In the wider context of labor organizing, protests, and arrests for trade union activism, Hartford Communists attempted to rally folks to demonstrate around child labor in tobacco, U.S. foreign policy and the threat of war, and against lynching and in defense of the nine imprisoned African American “Scottsboro Boys” in Alabama. But the organized Right-wing was also present. In 1932, the Ku Klux Klan held a 300-strong demonstration in Greenwich.

In line with the Soviet policy of seeking new alliances with allies on the socialist Left, “United Front” committees were formed in the mid-1930s. In April 1936, the CP worked in the Socialist Party electoral campaign in New Britain. That month, Richard Farber wrote to the CP headquarters in New York about plans to hold an antiwar meeting at Russian Hall on Cherry Street in Waterbury, where he was acting as Party Section Organizer, adding, “Is there a Party Portuguese paper printed and other materials in that language? We have workers who are interested in getting this material.”[11] Farber also chaired the Waterbury United Front for May Day committee that met at the YMCA. The CP in Connecticut also worked to elect national candidates. Earl Browder, the CP Presidential candidate, drew 1,400 people to his campaign speech at the Bushnell in Hartford.[12]

Local and national public sentiment against fascism grew stronger in the months after the Hartford Woman’s Club meeting of 1937. A Trinity College professor, Haroutune M. Dadourian, arranged for a group of artists from Hartford Federal College to paint on the Old State House lawn at lunchtime to draw attention to an upcoming appearance of the Spanish ambassador at the Bushnell. The ambassador was raising money for an American Relief Ship for Civil War orphans. Jerome Stavola, Alton S. Tobey, Bob Beebe, and Joseph Scarozzo began work on four large posters, including one of a Spanish child with a rifle, wearing Nazi regalia-a reference to the German invaders. As a crowd gathered, some objected to the swastika and others murmured about “Communist propaganda.” The police ordered the swastika painted over, but the artists had managed to generate publicity for the Ambassador’s visit nonetheless.[13]

Spain and Its Aftermath

DeMaio arrived in Spain on January 6, 1937, and Farber on June 28. Both marched over the Pyrenees, and saw long terms of service on the fighting fronts. Farber served for a year in Aragon, the Central Front and Teruil, as an infantryman, runner, supply clerk, and quartermaster’s clerk. DeMaio served in Ebro, one of several postings. Farber returned from Spain in November 1938.

The circumstances surrounding DeMaio’s March 1939 departure are cloudy. He was accused by Maxwell Wallach, father of a missing Brigader, and by several other ex-volunteers, some of whom may have been government informers, of meting out violent and even capital punishment against deserting or dissenting Brigaders in Barcelona.[14] Such accusations, made against other volunteers as well, circulated amongst Brigade veterans for years, fueled by the many conflicts between Communists and anarchists and the followers of the POUM (United Spanish Workers’ Party).

In DeMaio’s case, charges were made by his accusers before HUAC, the House Un-American Activities Committee (or Dies Committee) in Washington, in 1940.[15] DeMaio’s actions remain a matter of speculation. What does seem clear is that DeMaio had more to do with security matters than his testimony before HUAC disclosed. A Russian archival file, recently published by Yale University Press, identifies him as an intelligence officer involved in reporting on personnel security questions.[16] The charges that he had been involved in the disappearance and, indeed, the execution of some missing Americans were never resolved in the U.S., and he denied these charges. His and others’ stories are part of the legacy of Stalinist practice, the machinations of anti-Communist investigations, and the sheer bitterness and fratricide of defeat. Knowledge of the iniquitous internal Soviet prison system and the Moscow trials against Stalin’s political opponents circulated. CP members in the U.S. harboring dissenting political differences had for years been expelled in branches as small as Hartford’s. These events and facts were certainly known to Farber and DeMaio.

Yet these men also demonstrated their solidarity with those fighting fascism in another way. After Spain, Farber worked in the small shops on Bartholomew Avenue in Hartford until 1942, DeMaio at the Terry Steam Plant. Both returned to the military — this time in the uniform of the U.S. Army. DeMaio was an infantryman and a platoon leader and fought in many battles, including the Battle of the Bulge. He was belatedly decorated for his war service, after a medal was refused him in the 1940s because of his political affiliations. After the war, DeMaio worked for 26 years as a field representative for the UE, largely in Minnesota, and then moved back to Old Lyme. He retired to California in 1986 where he died in 1999. Farber moved to New York in 1944 with his family and died in West Hartford in 1985, his later political life and circumstances less-known.

The passion for social justice of the Lincoln Brigaders continued long after the 1930s. Brigade veterans sent an ambulance to Nicaragua during the recent war, protested South African apartheid, and marched against the bombing of Iraq in 1991.[17] In the 1980s DeMaio appeared in a peace demonstration in Connecticut and lectured regularly in area schools about Spain. In 1997, the Spanish Parliament conferred honorary Spanish citizenship upon the surviving members of the International Brigades. Some Lincoln Brigaders made the journey back across the Atlantic to Madrid flushed with pride, but equally burdened with the memory of those who had fallen.

Susan D. Pennybacker was Associate Professor of history at Trinity College in Hartford. Paul Kershaw was a graduate student in history at New York University.

[See print version for footnotes, order at ctexplored.org/backissues]