(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2015/16

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

When the International Silver Company formed in 1898, it was already a colossus. The businesses that merged to form the new company produced about 70 percent of the silverware manufactured in the U.S., according to company historian Edmund P. Hogan in An American Heritage: A Book about the International Silver Company, (Taylor Publishing, 1977). Various competitors tried to capture a controlling share of its stock or trust-bust it using federal anti-trust statutes, according to Earl Chapin May in A Century of Silver: Connecticut Yankees and a Noble Metal, 1847-1947 (Robert M. McBride & Company, 1947). Its sheer size also made it easy to disparage; it was looked down on as middlebrow or hyper-commercial because it made silver items to be sold at many different price points. Even today, the company’s reputation among collectors and museums is playing catch-up with those of the elite manufacturers such as Tiffany and Gorham. Yet International was a gem among Connecticut industries, and its legacy shines today.

Seventeen companies formed International, from Meriden, Wallingford, Bridgeport, Hartford, other Connecticut towns, Brooklyn, New York, and as far away as Toronto. International produced wares ranging from the thinnest silverplate to elegant hand-chased sterling. Its main products fell into two categories: flatware (eating utensils made from sheets of metal) and hollowware (hollowed-out items such as pitchers, vases, bowls). Its catalogs offered myriad other products too, sometimes even surprising ones—ship replicas, coffin handles, and men’s cigarette cases embossed with half-nude nymphs. Many of the component companies kept stamping their own names or marks on their pieces, along with “IS” or “International Silver” as a secondary mark. Later, International marketed different lines of silver bearing several subsidiary brands, including Simpson, Hall, Miller & Co.; Wilcox & Evertsen Fine Arts; and Wm. Rogers.

It was the economic downturns of 1893, 1894, and 1896 that convinced the smaller silver companies to band together to take advantage of economies of scale. The new mega-company did not turn much of a profit for several years, but then it took off. George H. Wilcox took the helm in 1907, becoming the first of several Wilcoxes to lead International. Throughout the years, many of the company’s top officers either came from Connecticut “silver families” with a history in the industry (including the Stevenses, Maltbys, and Munsons) or else “came up from the bench”—the silversmith’s workbench.

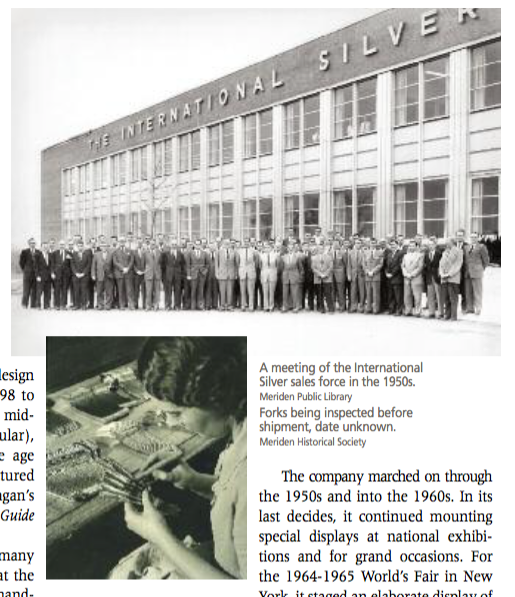

International dominated Meriden and nearby Wallingford, and in time many of the component companies were consolidated in those towns. International factories dotted both communities. Somewhere along the way Meriden began to be known as “Silver City.” Eventually the company employed more than 5,000 people according to May. It provided paid vacations, a ballpark, company trips, and enough camaraderie and security to retain many workers for their whole careers. The workers included modelers, chasers, spinners, blank cutters, trimmers, buffers, engravers, polishers, inspectors, and a raft of others who kept the books, sold the finished products, and shipped those products out.

International dominated Meriden and nearby Wallingford, and in time many of the component companies were consolidated in those towns. International factories dotted both communities. Somewhere along the way Meriden began to be known as “Silver City.” Eventually the company employed more than 5,000 people according to May. It provided paid vacations, a ballpark, company trips, and enough camaraderie and security to retain many workers for their whole careers. The workers included modelers, chasers, spinners, blank cutters, trimmers, buffers, engravers, polishers, inspectors, and a raft of others who kept the books, sold the finished products, and shipped those products out.

From the beginning, International advertised heavily and intelligently. In 1910, an invented character called “The 1847 Girl” began to smile personably from magazine pages and cardboard cutouts stationed in retail shops. Her job was to draw attention to one company brand, Rogers Bros. 1847 silverplated flatware. The date evoked old times and tapped into the growing taste for colonial revival-style silver. The bonneted “Girl” became so beloved that International had to have her costume sewn up for sale in little girls’ sizes.

During the Great Depression, International kept bright magazine ads running to display its more affordable flatware. During World War II, despite metal restrictions, the company continued to make and advertise some sterling flatware. The ads generally pictured rather wistful, staged photos of beautiful young women waving their dashing men off to war. In 1947 the company began to advertise on television, sponsoring programs such as the Show of Shows.Hogan devotes a chapter to International’s advertising, including the 1847 Girl.

World War II was a high point for International—although not via its usual product lines. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the company took only a few months to convert to war production. It had already established a lab for metallurgical and chemical research before the war and then enlarged it in 1941 in anticipation of conflict. The factories’ war output was mammoth and efficient, and the company won many government awards for quality. According to May, International’s managers consistently refused offers of help from self-appointed outside “experts.” The existing work force figured out how to make everything from ultra-precise surgical instruments to cluster bombs filled with treacherous magnesium. Among other war products, International made 12.4 million M1 carbine magazine assemblies; 7.7 million plane, bazooka, and gun parts; 25.9 million incendiary bombs; 216.8 million machine gun links; and 35 million pieces of flatware to feed the troops. The totals were listed in a “war work” brochure the company published later to salute its employees’ accomplishments. International served as the prime contractor in 447 war contracts and devoted nearly 1.3 million square feet of factory space to war work.

International’s long years of steady business success depended on designing silver products that had commercial appeal. In its production lines, the company seldom aimed for exclusivity or high art. At the same time, it made every effort to be stylish and up-to-the-minute. Its products went through the major American design phases from the late Victorian/Edwardian (1898 to the 19-teens), through art deco (1920s to mid-1940s), colonial revival (continuously popular), Scandinavian (1930s and after), to the space age (1960s and beyond). Its flatware designs are pictured in a number of reference books, such as Tere Hagan’s Sterling Flatware: An Identification and Value Guide (Schiffer Publishing, 1999).

International’s long years of steady business success depended on designing silver products that had commercial appeal. In its production lines, the company seldom aimed for exclusivity or high art. At the same time, it made every effort to be stylish and up-to-the-minute. Its products went through the major American design phases from the late Victorian/Edwardian (1898 to the 19-teens), through art deco (1920s to mid-1940s), colonial revival (continuously popular), Scandinavian (1930s and after), to the space age (1960s and beyond). Its flatware designs are pictured in a number of reference books, such as Tere Hagan’s Sterling Flatware: An Identification and Value Guide (Schiffer Publishing, 1999).

Over the years, International employed many young designers who had learned their trade at the Wilcox Technical School in Meriden, from a demanding instructor named Ernst Lohrmann (1889-1967). Lohrmann, an artist and silversmith himself, set students to drawing copies of “wonderful old decorative plates” from his library, flatware designer Siro Toffolon remembered in a 2011 interview with me. When the students felt they had finished a splendid likeness, Lohrmann would tell them to erase it and start again. The Rhode Island School of Design also contributed talent, particularly one of the company’s only female designers, Lillian Helander (1899-1973).

International devoted a division to ecclesiastical silver. Products might be elegant altar plates for large churches or portable crosses and communion sets for military field altars. Many World War II chaplains wrote to thank the company for making the sets, which they found easy to manage and conducive to worship in rough circumstances. Another division made silverware for hotels, railroad lines, shipping companies, and the dining halls of naval officers. Clients included the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York City, the New York Central Railroad, United Airlines, and dozens more. Collectors hunt for these customized items.

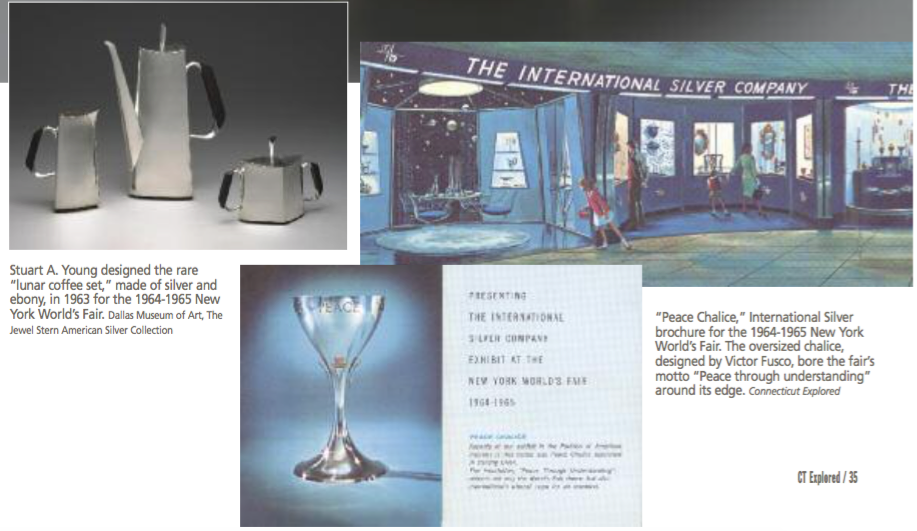

The company marched on through the 1950s and into the 1960s. In its last decides, it continued mounting special displays at national exhibitions and for grand occasions. For the 1964-1965 World’s Fair in New York, it staged an elaborate display of the company’s products from the past and saluted the nation’s concept of the space-age future. Among the items on display were some that had been specially hand-wrought in sterling for the fair, including the Peace Chalice—a towering vessel designed by Victor B. Fusco. In the futuristic Moon Room, invisible guy wires held clear plastic chairs and a plastic table in midair, while specially designed lights glittered celestially overhead. On the table sat a delicate sterling centerpiece twinkling with tiny spinel sapphires and brushed to a fine satin finish. Designed by Robert J. King, it featured a sphere of little spokes—obviously a reference to the shapes of stars and satellites. The accompanying flatware was stylishly asymmetrical.

The company marched on through the 1950s and into the 1960s. In its last decides, it continued mounting special displays at national exhibitions and for grand occasions. For the 1964-1965 World’s Fair in New York, it staged an elaborate display of the company’s products from the past and saluted the nation’s concept of the space-age future. Among the items on display were some that had been specially hand-wrought in sterling for the fair, including the Peace Chalice—a towering vessel designed by Victor B. Fusco. In the futuristic Moon Room, invisible guy wires held clear plastic chairs and a plastic table in midair, while specially designed lights glittered celestially overhead. On the table sat a delicate sterling centerpiece twinkling with tiny spinel sapphires and brushed to a fine satin finish. Designed by Robert J. King, it featured a sphere of little spokes—obviously a reference to the shapes of stars and satellites. The accompanying flatware was stylishly asymmetrical.

The American Bicentennial in 1976, another event that the company celebrated with a big splash, was a swan song, though some did not yet realize it. Queen Elizabeth II visited the United States that year and received a gift made by the company: a chess set with American revolutionaries rendered in pewter on one side and gold-plated British soldiers on the other. The company made less expensive commemoratives too, including a boxed set of 13 silverplated spoons, each honoring one of the 13 colonies.

The American Bicentennial in 1976, another event that the company celebrated with a big splash, was a swan song, though some did not yet realize it. Queen Elizabeth II visited the United States that year and received a gift made by the company: a chess set with American revolutionaries rendered in pewter on one side and gold-plated British soldiers on the other. The company made less expensive commemoratives too, including a boxed set of 13 silverplated spoons, each honoring one of the 13 colonies.

Many problems beset American silver companies in the 1970s, including metal price spikes, high interest and inflation, and overseas competition. Reduced tariffs in 1976 allowed inexpensive Asian-made flatware to invade the U.S. market. American lifestyles became more casual, too; perhaps a hostess would rather display a piece of hand-thrown pottery in the dining room than a formal silver coffee service.

Although all U.S. silver companies shrank during this period, and many eventually closed, International in particular saw its profits redirected to and its reputation relied upon to facilitate the acquisition of other, nonsilver businesses. These businesses, producing such things as paint and office products, were turned into a conglomerate named Insilco. In the 1960s, management issued securities three times in International’s name in order to acquire stock in the other businesses. By law, these issuances were recorded in the Securities and Exchange Commission News Digests (February 26, 1965, August 30, 1967, and March 13, 1969). The upshot was that although Insilco was formed under the flag of International, management’s interest shifted to running multiple and varied businesses—some far away from Meriden. (The New York Times, March 5, 1972). Although it was once the parent company, International in the end became the neglected child, as business journalist Subrata N. Chakravarty pointed out in Forbes (September 28, 1981). The last remnants of the silver business were sold by 1983. One wonders what International might have become if management had tried to capitalize on the company’s remarkable expertise in metals rather than using its assets to balloon into a conglomerate.

The last day for International’s venerable plated hollowware division was March 20, 1981, according to a 2010 telephone interview with Stuart Young, who was the director of design at the time. As part of upper management, Young knew the closing was coming at some point (most workers did not). But, looking out his office window, he was still shocked to see buses pulling through the main gate that day. Men spilled out carrying large sticks, “like billy clubs,” Young recalled. They stood by each door of the factory to discourage any resistance. Inside, a loudspeaker ordered employees to pick up their personal belongings and leave immediately. Young and everyone else complied.

In later interviews, Young and several other International managers told what had gone on before and after that ugly day. Each had his own view of the process, but certain themes emerge from their recollections: senior management’s ignorance of the silver industry, the selling off of divisions, workers’ being let go, ominous warnings about productivity, and flatware dies’ being sent to Puerto Rico.

The process of undoing International had begun almost imperceptibly. In 1957 Durand B. Blatz became the controller of the company. He was not from a silver family, nor did he come up from the bench. By 1966 he had become International’s CEO. He had already begun the diversification planning that the company directors and other officers found convincing.

Insilco openly acknowledged the process by which International’s profits were siphoned off in An American Heritage. Hogan notes, “The Insilco diversification was, of course, funded by the resources of the International Silver Company. Without the strong balance sheet of the company, the expansion of Insilco would not have been possible.”

How much of International’s artistic legacy, its working drawings, prototypes, and exhibition silver, survived after 1981? The day after the buses arrived, Young explained to me, he was told to go back into his department and, except for a few designs already sold to Oneida, destroy the hollowware drawings on file there. “I spent three or four days shredding,” he noted. “I could see my signatures on the drawings. It was my life.”

The Meriden Historical Society has some company documents, but Young and other former company designers and historical society volunteers wonder about the fate of some valuable one-off silver items. Many pieces specially created for the 1964-1965 World’s Fair “have not come to light,” according to collector/author Jewel Stern in Modernism in American Silver: 20th Century Design (Yale University Press, 2005). Stern was able to trace the peace chalice. It had become a “corporate trophy” for the Times Wire & Cable Company of Wallingford—makers of coaxial cable and the first company bought in International’s diversification campaign. Sadly, the owners had the rather noble inscription about peace removed and substituted an inscription in praise of commerce. The Moon Room was partly recreated in a special exhibition by the Dallas Museum of Art in 2006. The exhibition celebrated the museum’s purchase of the Moon Room centerpiece, which luckily had survived International’s chaotic closing.

The Dallas Museum collection numbers close to 200 pieces by International. In addition, the company’s silver work has been displayed by the Brooklyn Museum, Newark Museum, and Cooper-Hewitt, the Smithsonian Design Museum. Smaller items are on view at the Meriden Historical Society.

Insilco did not have the glorious future that Blatz and others planned for it. After being taken over itself, it began to founder in the late 1980s. It went bankrupt in 1991—only a decade after the plated hollowware division was shut in Meriden. At that point, it was buried in $800 million of debt, according to the International Directory of Company Histories (Vol. 16. St. James Press, 1997)—a sad end for an enterprise that had been healthy for nearly a century. Bits of the company churned through other ownership after that, but Insilco as a conglomerate and International as a corporation were gone.

Despite the painful undoing of International, a renaissance is underway for the company—among collectors, researchers, and museums. A number of International’s designers are known and acknowledged today. Perhaps the most notable is Alfred G. Kintz (1884-1963), who was born to a Meriden family descended from German-speaking woodcarvers. His older brother Robert was a designer and modeler at International, and his son Robert spent a career there too. Kintz’s work was first reported at length by me in Silver Magazine (September-October 1986). A pair of rare condiment servers he designed was on display in 1987 at the Smithsonian Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., and then went on tour for two years.

Kintz is noted especially for his sophisticated 1928 Art Deco hollowware. In his long career, he also designed 44 flatware patterns, most of them sterling. “Royal Danish” and “Prelude” (both 1938) are among the tiny handful of American sterling patterns still being made from old dies; they’re produced by a small offshore manufacturer and then sold under the International name. (Only about 12 patterns from all the big manufacturers combined are still being made, so for one designer to have two of them is remarkable.) Kintz designed both flatware and hollowware in sterling. When one of his flatware patterns went into production, he often designed matching coffee services, trays, candy and cake dishes too, his son explained in a telephone interview in 1986. The hollowware—which was less likely to be copied by competitors—was not usually patented. For hollowware in general, this makes attributing some designs more difficult for researchers.

Kintz is noted especially for his sophisticated 1928 Art Deco hollowware. In his long career, he also designed 44 flatware patterns, most of them sterling. “Royal Danish” and “Prelude” (both 1938) are among the tiny handful of American sterling patterns still being made from old dies; they’re produced by a small offshore manufacturer and then sold under the International name. (Only about 12 patterns from all the big manufacturers combined are still being made, so for one designer to have two of them is remarkable.) Kintz designed both flatware and hollowware in sterling. When one of his flatware patterns went into production, he often designed matching coffee services, trays, candy and cake dishes too, his son explained in a telephone interview in 1986. The hollowware—which was less likely to be copied by competitors—was not usually patented. For hollowware in general, this makes attributing some designs more difficult for researchers.

Other International designers appear in Stern’s lavishly illustrated Modernism in American Silver, which bears more than 100 text citations to International and dozens of photos of its production work. The book represented the first time the company’s designs received a substantial published showing.

In April 2015, Sotheby’s auctioned a silverplated cocktail shaker made by International circa 1930. Shaped as a lighthouse, it was detailed with pedimented windows, a beacon lamp, and a lookout gallery. An unidentified bidder paid $15,000 for it. Clearly, the International Silver Company has begun to get its due.

In April 2015, Sotheby’s auctioned a silverplated cocktail shaker made by International circa 1930. Shaped as a lighthouse, it was detailed with pedimented windows, a beacon lamp, and a lookout gallery. An unidentified bidder paid $15,000 for it. Clearly, the International Silver Company has begun to get its due.

Patricia F. Singer is a former journalist for the World Bank in Washington, D.C. She has written about International Silver for Silver Magazine. She’s greatly indebted to the Meriden Historical Society volunteers for their help with this article.

Explore!

Read more stories about iconic products Made in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.