By Elizabeth Warren

(c) Connecticut Explored Spring 2010

Scan any late 19th-century newspaper and you will find numerous jokes at the expense of female lawyers and even more at the expense of women in general. Although these fillers, nestled among ads for “dwellings to let,” “horses for sale,” and “ladies’ coaching umbrellas and parasols” may seem quaint, they represent a profoundly ingrained sexism whose future, for the first time in history, was uncertain.

The issue at hand was whether women were competent: whether they possessed judgment and, ultimately, whether they should have the right to vote. Society began to hammer out answers to those questions, after abolitionist women carved out unprecedented roles for themselves in public life. One intersection on the road toward suffrage was the question of whether women could hold public office such as pension officer, notary public, postmaster, or attorney. And one of the most important victories for women’s competence was the admittance of Mary Hall to the Hartford County Bar in October 1882.

Hall was the first woman in the state to be admitted to the bar. Her success was not an isolated victory for women’s rights but one of a patchwork of such battles that took place across the United States from 1869 until the passage of the 19th Amendment after World War I. Hall’s case was singularly important, however, because, according to women’s legal historian Virginia Drachman in Sisters in Law (Harvard University Press, 2001), it “represented one of American women’s first successes in using the judicial system to change radically their legal status.”

In 1869, Myra Bradwell of Chicago, wife of a prominent Chicago lawyer and publisher of the influential if controversial Chicago Legal News, became the first American woman to apply to the bar. Papers from coast to coast followed her bid for admission to the Illinois bar. When that state’s supreme court denied her admission, she immediately appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice Joseph Bradley also denied her claim, arguing that “the civil law, as well as nature herself, has always recognized a wide difference in the respective spheres and destinies of man and woman.” He continued, “Man is, or should be, women’s protector and defender. The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for any of the occupations of civil life. The constitution of family organization, which is founded in the divine ordinance, as well as in the nature of things, indicates the domestic sphere as that which properly belongs to the domain and functions of womanhood.” The newspapers agreed, making their stance clear with headlines such as The Indianapolis Sentinel’s “WHERE WOMEN MUST STOP.”

Judge Bradley left a loophole, however, noting that “[i]t is true that many women are unmarried and not affected by any of the duties, complications, and incapacities arising out of the married state.” Bradwell, as a married woman, did not exist legally apart from her husband and was therefore unable to own property, sue or enter into legal contracts—or, as it turned out, practice law. But a new generation of young women would soon exploit that very chink in tradition’s armor.

A number of the women who next challenged women’s exclusion from the legal profession were the daughters of liberal parents on the East Coast. Mary Hall, born in 1843, was one of seven children of a successful farmer and miller in Marlborough, Connecticut. Hall graduated from Wesleyan Academy in Massachusetts in 1866 at age 23. She became the chair of mathematics at the LaSalle seminary outside of Boston in the mid-1870s but was “not enthusiastic” about teaching, one of the few professions then open to women. Her interest in public matters led her to study law instead. In 1877, she approached her brother Ezra, already a lawyer in Hartford and Connecticut state senator, about studying law in his office. He discouraged her outright. He changed his mind, though, after she tore through legal briefs with the interest and understanding of a born lawyer.

Law schools were largely founded in the mid-19th century, but most people learned the profession through apprenticeships to established lawyers. Men seeking to become lawyers merely needed to pass a successful examination in front of the bar and be in good standing as a citizen in order to be granted the title of lawyer by the Court.

Ezra died suddenly in April 1878 and left his sister to chart her own course in Hartford. A year later she began to work in the office of the state Supreme Court reporter John Hooker, husband of the suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker, the youngest sister of author and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Hookers were prominent citizens and were influential in political and suffrage circles in Connecticut and Washington.

Isabella was a writer, thinker, and activist who worked closely with Susan B. Anthony and the National Women’s Suffrage Association for decades. For both Hooker and Anthony, all work on women’s rights was a means toward winning the vote—and Hooker preferred using a judicial rather than legislative path to suffrage.

Although Hall was more than 20 years the Hookers’ junior, she impressed the pair and the Hartford judicial crowd as well. Her legal competence was undeniable. She was appointed a commissioner of the Superior Court in 1879 (while still studying to become a lawyer) and, according to The Hartford Courant, her appointment became a “sensation in the state, although her appointment was approved by Governor Hubbard…and other prominent gentleman.”

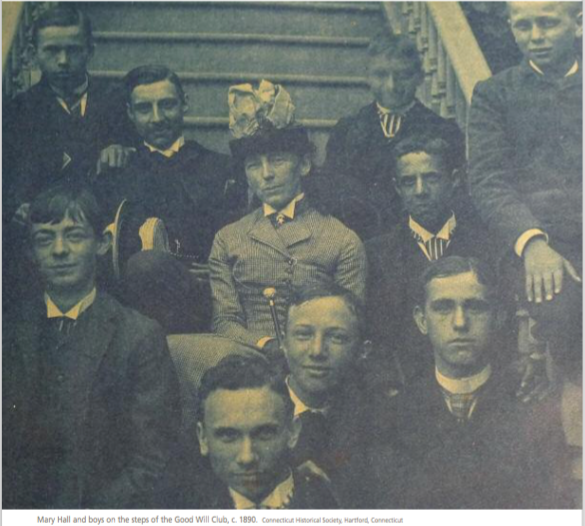

While Hall was working in John’s office, Isabella introduced her to the cause of suffrage, which would become, in a way, a theme of her life. At the same time, she began to read to a group of poor Hartford boys; this group evolved into the Good Will Club, established in 1880, and later the Boys & Girls Clubs of America. The goal of the club was to teach boys to become good citizens. She taught them how to participate in government and civic affairs.

At the group’s second meeting, the boys drafted a constitution that gave each boy older than eight the right to apply for “citizenship” in the club, to vote, run for office, and carry the coveted member badge. Hall strove to create a progressive club that practiced prevention rather than reform. Ten years later, Hall reflected that her aim in starting the club was to “amuse, instruct and befriend these boys, and make this institution a perpetual blessing to the city.” Her charity work gave her a kind of moral legitimacy upon which she could advance her own largely groundbreaking career.

In the early months of 1882, when Hall was contemplating whether or when to take the bar examination, she was already well known within the state for her appointment as a commissioner to the Superior Court and through the activities of the Good Will Club. She was seen as a respectable woman of good breeding who had chosen not to marry and had made a name for herself in a sphere that had become not only acceptable but sacred for women, namely, reform.

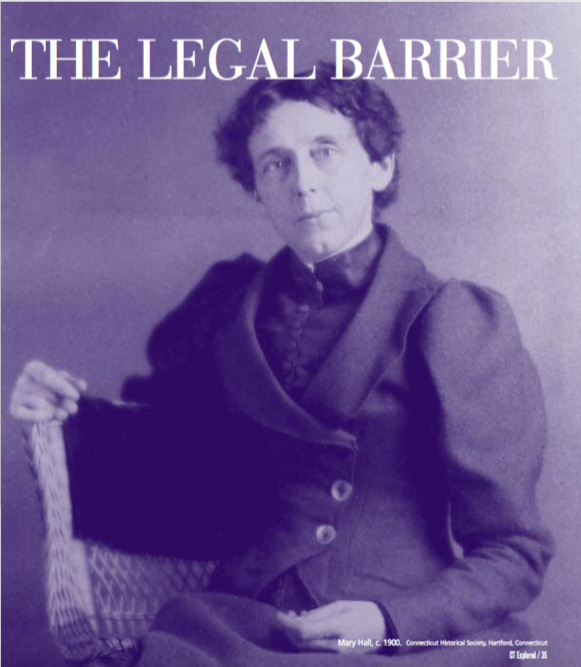

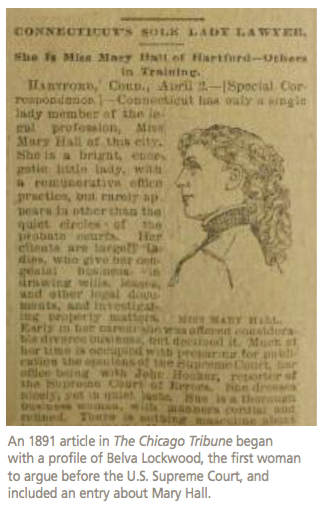

This status helped shield Hall, to some degree, from the typical treatment of female lawyers by the press across the United States where they were the punch line of scores of jokes, and their every move was reported. She received a different kind of treatment: Hall was among the female lawyers whom the press placed on a pedestal. The papers lauded Hall and others as paragons of womanly virtue, describing their hair, their clothes, their manners, and their offices without mentioning their work. This treatment was reserved for those who did legal work that did not require them to appear in court. They were called “sweet” and “pretty,” and they worked in lovely offices full of “pots of geraniums.” A profile in The Chicago Tribune in 1891 headlined “Lawyers in Petticoats” described Hall, a few years into her practice, as working quietly in Hooker’s office “dressed nicely yet in quiet taste. She is a thorough businesswoman with manners cordial and refined. There is nothing masculine about her in any respect.”

A fickle and unrelenting press was not the only challenge facing women attempting to practice law. Female lawyers across the country faced nearly uniform prejudice against their legitimacy. They were chastised by judges and insulted by opposing council for appearing in court. In the years leading up to Hall’s admission to the bar, it was still extremely difficult to be admitted to the bar and impossible in some states. Nettie Tator, the first female lawyer on the Pacific coast (later admitted in 1882), was refused admission to the bar of Santa Cruz, California in 1872. The infamous Belva Lockwood was refused the right to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court. And Ada Kepley, who had graduated with a law degree from the old University of Chicago in 1870, was denied entry to the Illinois bar in the wake of Lockwood’s loss. Lelia Robinson, of Massachusetts, was refused admission to the bar through that state’s courts in 1882. The Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that only the state legislature could grant a woman admission to the bar (which, in Robinson’s case, it ultimately did that same year).

On March 25, 1882 the Hartford Bar Association took up the issue of whether Mary Hall could even take the bar examination. The Courant reported that John Hooker spoke to her qualifications and a recommendation was made to “refer the whole matter to a select committee, to report upon the legality of her admission, provided she passed the examination successfully.” That motion was promptly rejected. It was then recommended that “she be admitted to examination, subject to the opinion of the court as to the legality of admitting her sex, and that the committee be requested to hold a special meeting for the examination of Miss Hall, and report the result to the annual meeting of the bar to be held next Friday.” This motion was carried.

Despite the obvious pressures surrounding the test, which was held in an open courtroom with an audience, Hall passed handily. The bar then appointed two attorneys, Thomas McManus (with the help of John Hooker), in favor, and Goodwin Collier, opposed, to argue the case in court. The Courant noted that she had passed her examination, stating that the judgment was “reserved for the Supreme Court.”

Judge Sidney Beardsley of the Superior Court reserved judgment for the Supreme Court of Errors, and the case went before the Supreme Court on May 5, 1882. Because the matter was such a high-profile one, the bar association printed up a resolution, a rarity outside of a kind of posthumous remembrance of a lawyer or judge’s accomplishments, stating that “the bar recommend[s] Miss Mary Hall for admission to the bar, saving the question of her eligibility as a woman.”

John Hooker wrote in his memoirs that a successful outcome was regarded then as “a very doubtful result.” Hooker himself, along with McManus, argued on Hall’s behalf and noted that Collier “made an elaborate argument on the other side.”

John Hooker wrote in his memoirs that a successful outcome was regarded then as “a very doubtful result.” Hooker himself, along with McManus, argued on Hall’s behalf and noted that Collier “made an elaborate argument on the other side.”

By statute in 1882 the Superior Court could “admit as attorneys such persons as are qualified therefor agreeably to the rules established by the judges of said court.” Collier, who argued against Hall’s admission to the bar, wrote in his brief that “the use of general language [the term “persons”] though sufficiently broad to include women, is not sufficient to show the intent of the Legislature to alter laws, customs and usages existing for centuries.” He continued that, “whenever the Legislature has intended to remove disqualifications of women, or to grant them privileges, it has used words clearly showing its intention.” He further argued that this question has already been decided “by the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, Illinois, and Wisconsin; also by the Court of Claims and the Supreme Court of the United States.”

Hooker and McManus argued that the word “person” in the statute included women alongside men, citing multiple dictionaries in their brief. This argument, that women are “persons” and are thus eligible for all the rights conferred to “persons” by laws across the country, was a line of reasoning made often by Isabella Beecher Hooker, who favored judicial decisions as a path toward suffrage. Despite all the prior cases, the judges disagreed with Collier’s argument and voted three to one in favor of Hall’s admission to the bar.

Judge John Park wrote in his decision that “we are not to forget that all statutes are to be construed, as far as possible, in favor of equality of rights. All restrictions upon human liberty, all claims for special privileges, are to be regarded as having the presumption of law against them, and as standing upon their defense, and can be sustained, if not at all by valid legislation, only by the clear expression or clear implication of the law.”

He wrote later that women had served successful terms as postmasters and pension officers across the country, positions analogous to that of attorney. He said that these positions “promote the public interest, which is benefited by every legitimate use of individual ability.”

The decision was reported across the country, with newspapers broadly echoing Chief Justice Park’s words: “All progress in social matters is gradual. We pass almost imperceptibly from a state of public opinion that utterly condemns some course of action to one that strongly approves it.”

The progress was gradual indeed, as resentment of female lawyers continued to flourish. In August 1882 The Central Law Journal opined, incorrectly referring to Hall as “Miss Mary Hooker,” that the “young woman” should “now vindicate the policy of the law, as interpreted by the court, by actually engaging in practice rather than indulge in the not unusual proceeding of misusing her license as an advertisement of a season upon her lecture platform.” What this journal fails to recognize is that female lawyers were de facto barred from having a normal practice and were thus forced to find other means to support themselves. Leila Robinson, who was admitted to the Massachusetts bar the same year Hall was admitted in Connecticut, wrote of the “embarrassments and difficulties” of finding legal work in Boston without experience in court—unable to support herself, she was forced to move West.

Hall too was greatly impaired by prejudice against her sex. While she continued to share an office with John Hooker (who remained the supreme court reporter despite being offered a seat on the bench), she worked almost exclusively for female clients and almost never argued a case for a client in court. Public opinion, she knew, kept her from speaking in court and also kept her from working on divorce cases. She worked for years in a kind of legal bubble.

Despite her vocational isolation, Hall continued to break barriers throughout her career. She was the first woman to become a notary public in the state (1884), and the first woman granted the right to sell real estate in Connecticut (1891).

Hall practiced law and sustained the Good Will Club through sheer grit, determination, and a modern marketing sense until her death in 1927. She lived to see the passage of the 19th Amendment. She remained a celebrity in Hartford, and around the country, for the rest of her life but was memorialized almost exclusively as a traditional, worthy woman who had sacrificed herself for the betterment of boys. At Hall’s death, 45 years after her admittance to the bar, there were only four female lawyers in Connecticut.

Elizabeth Warren is a producer at CPTV in Hartford. She discovered Mary Hall while working on a documentary about philanthropy in Connecticut.

Explore!

“The Trailblazing Bessye Bennett,” Spring 2014

Read more about John and Isabella Beecher Hooker in “The Spirits of Reform.”

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.