By Katherine J. Harris

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2016

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The right to vote is an expression of political participation, human dignity, and control of one’s destiny. For the majority of people of African descent in Connecticut in the 1700s emancipation from slavery, the rights of citizenship, and voting rights were linked. Connecticut legislators passed a Gradual Emancipation Act in 1784 that eliminated hereditary enslavement (freeing only those born into slavery after March 1, 1784 at age 25, that age was lowered to 21 in 1797), and finally abolished slavery in 1848. Numbers of African Americans in Connecticut obtained their freedom, purchased property, organized churches and other institutions, and attained education. Despite these achievements, the state of Connecticut limited the full rights of citizenship even for the free African Americans who fought for the independence of the United States from England.

Throughout the 18th century and for much of the 19th century African Americans expressed their goal for achieving political empowerment in part by electing “Negro Governors,” or “Black Governors.” [See “Monument to the Black Governors,” Summer 2004, ctexplored.org/monument-to-the-black-governors/.] These terms conveyed honor and leadership within the African American community, though the position carried no political authority within the white power structure. A second avenue to political participation was through voting in state and local elections. Some African American men were able to vote before 1812. A September 7, 1803 editorial in the Connecticut Courant suggested that “two citizens of colour” in Wallingford who were Democrats (the contemporary Democratic Party) and “free” had voted. The editorial, more than 200 years old, read:

Two Plain Questions.

It seems that in the town of Wallingford there are two citizens of colour, both democrats, and both admitted to be free of this state by the democratic Justices and Select-Men of that town.

Question I. In case the aforesaid citizens should at the next election of representatives to the General Assembly, obtain a clear majority of votes to represent said town, whether they would be returned as duly elected?

Question II. If chosen and returned as aforesaid. Would they be admitted to seats in the House of Representatives of this State?

A plain answer by some persons who is acquainted with the laws and the rights of the people of this State would greatly oblige.

[signed]A White Freeman.

The designation “freeman” was a social designation denoting a property owner with voting rights and other rights to participate in political activities. The editorial suggests that African Americans not only voted but held elective office as well. Between 1812 and the passage of the new state constitution in 1818, Connecticut political authorities enacted laws to restrict the suffrage to white adult men. African Americans protested invoking the language of the Revolutionary War patriots: “no taxation without representation.”

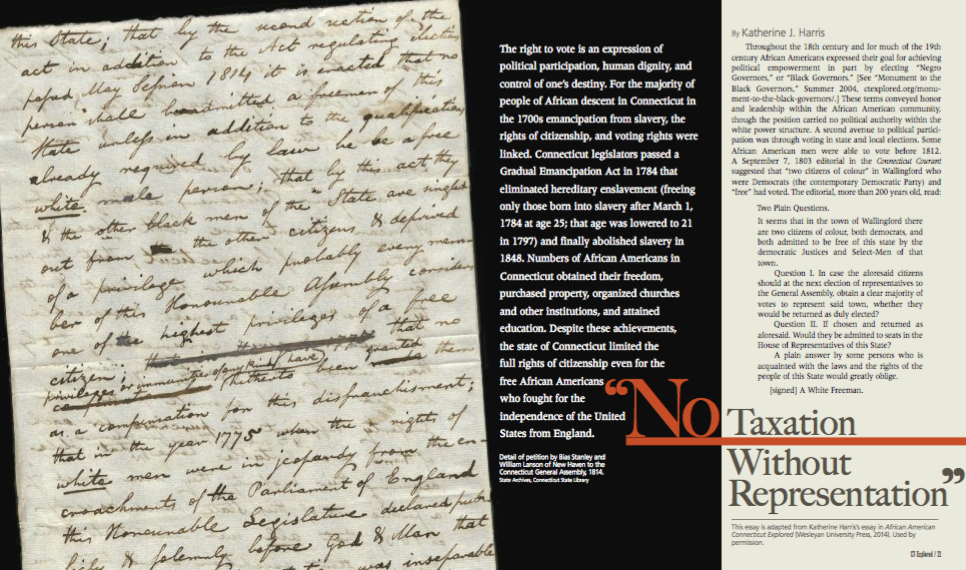

In 1814, the General Assembly denied the franchise to African Americans. Bias Stanley and William Lanson of New Haven asked that they be exempt from paying taxes since they could not vote. Lanson was not exempted from tax obligations. New Haven records (in the collection of the New Haven Museum) contain Lanson’s receipts showing proof of payment of his taxes.

More petitions of protest followed Lanson and Stanley’s 1814 petition. In 1817, Josiah Cornell, William Laws, William Harris, Deppard [sometimes Dedford]Billings, Ira [sometimes Tossett]Forset, Olney M. Douglass, Anthony Church, Thomas Hamilton, Joseph Facy, and John Meads—free persons of color from New London and Norwich—presented petitions against paying the poll tax when they could not vote. (A poll tax was a monetary fee African Americans were required to pay in order to vote.) The Connecticut General Assembly rejected the petition. The 1818 Connecticut constitution enacted Article VI, Section 2. It affirmed the right of all white males to vote if they were 21 or older and possessed property worth at least seven dollars, among other requirements.

The issue of voting-rights restriction emerged again in 1823 when Isaac Glasko in Griswold, a man of African American and Native American descent, presented a petition asking for exemption from taxation due to a lack of voting rights. The general assembly rejected the petition.

In the 1830s, Amos Gerry Beman moved from Middletown to New Haven, where he connected with the interracial abolitionist community and continued to work for African American voting rights. His sister-in-law Clarissa Beman carried on her family’s involvement in the antislavery struggle as a founding member of the Colored Female Anti-Slavery Society of Middletown. African American voting-rights activists linked their advocacy for political inclusion to a wider objective to abolish slavery and fulfill democratic principles enshrined in the nation’s Declaration of Independence. The 1839 petition by residents of Middletown argued,

[T]he last reason is of much weight—the violation of it was the great moving cause of the revolution—and if to enforce that principle a whole nation took up arms, your petitioners ask whether it should by your Hon. body be regarded as a … chimerical principle; or one of practical application? Some of us … fought and bled in a glorious struggle to establish that very principle which (as regards application to us) has been denied. Have we not reason to complain?

The Connecticut State Library Archives contains 26 sets of papers from African Americans in Hartford, New Haven, New London County, Middletown, and Torrington regarding the right of African Americans to vote. These additional petitions were presented to the General Assembly between 1838 and 1850. In 1845 members of Hartford’s African American community, followed in 1850 by members of New Haven’s African American community, petitioned the General Assembly to amend the State Constitution by removing the provision that granted the franchise only to white adult men. African American men and women signed the petitions. The general assembly rejected all the petitions. In 1842, residents of Hartford presented a petition that said:

To the Honorable, the House of Representatives of the State of Connecticut: The undersigned Free People of Color of the town of Hartford in the County of Hartford respectfully pray your honorable body to pass a resolution proposing such amendment of the second section of the sixth article of the Constitution of this State as shall secure the elective franchise to all men the requisite qualifications, irrespective of color.

Among those who signed the document were James Mars, James W.C. Pennington, and George Jeffrey and Leverett Beman from Middletown. George Jeffrey was a barber by trade and a political activist who became a pivotal member of the congregation at Parker Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Meriden during the late 19th century. Jeffrey was a prime mover in the Meriden-area Lincoln League that African Americans organized to advocate for black voting rights during the late 19th century. Named in honor of President Abraham Lincoln, this organization drew African American members from around the country to carry on the unfinished work of achieving full citizenship, voting rights, and economic opportunity.

Although Connecticut’s legislators rejected the petitions, African Americans mounted pressures to transform the political system. The 1850 petition from New Haven’s black community listed signatures from both men and women. This is important, as it demonstrates that African American men and women joined together in a common effort to obtain the franchise for men. The petition requested that the legislature “take the necessary measures for amending the Constitution of this State by expunging the word white in the first line of the 2nd Section of the 6th Article of Said Constitution.”

In 1870 the states ratified the 15th Amendment, which stated that no one should be denied the right to vote based on race or previous condition of servitude (though women, black or white, would be excluded until 1920). After considerable and often acrimonious debate, the Connecticut General Assembly amended the state constitution to comply with the federal amendment, which empowered most African American men with the right to vote. Still, voter intimidation, poll taxes, the grandfather clause, and other devices disfranchised many eligible African American voters across the United States. Some of these tactics included literacy tests requiring the prospective voter to interpret passages of the U.S. Constitution, while the grandfather clause based a person’s eligibility to vote on whether the person’s grandfather had voted. In Connecticut these tactics were not as pervasive as in other parts of the country, but even so voting rights remained insecure for African Americans. When the states ratified the 19th Amendment that granted women voting rights in 1919, African American women’s access to the franchise was still curtailed due to race.

While African American women in Northern states such as Connecticut had greater legal access to the polls, in Southern states and other states such as Oklahoma, literacy tests, poll taxes, and the grandfather clause were among the many legal restrictions that disfranchised African American women and men. Drawing attention to disfranchisement and the under-representation of black women voters, the NAACP’s Crisis published two “Votes for Women” issues, one in September 1912 and the other in August 1915. Determined to secure political participation, African American Mary Townsend Seymour, co-founder of the local NAACP in Hartford, was a leading advocate for social justice and voting rights. [See “Mary Townsend Seymour: Audacious Alliances,” Summer 2003]

Despite late-19th-century court challenges over practices such as those listed above that limited or prevented black voter participation, it was not until the 1960s phase of the civil rights movement that activists were able to secure federal safeguards for the franchise. The African American community’s effort to achieve this important right of citizenship was based on coalition building that attracted national attention. Congress passed and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The 24th Amendment ratified in 1964, outlawed the poll tax. The 1965 Voting Rights Act prohibited literacy tests and the grandfather clause. Signed into law in 1993 during the William J. Clinton administration, the National Voter Registration Act reinforced the right of all citizens to participate in the political process. Still, new challenges on the state and national levels continue to restrict the full exercise of political rights. But the inclusion of young people and members of the Latino and Latina communities and other underrepresented groups in the political process has been an important result of the African American struggle for the franchise. For African Americans in Connecticut, these events could be viewed as a fulfillment of their efforts to expand the electorate and the democratic process.

This essay is adapted from Katharine Harris’s essay in African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

Explore!

“The Constitution of 1818 and Black Suffrage: Rights for All?“, Fall 2018

Read more stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014)

Over 50 essays by many of the state’s leading historians and edited by Connecticut Explored’s publisher Elizabeth Normen document the long arc of the African American experience in Connecticut from the earliest years of the state’s colonization around 1630 and continuing well into the 20th century. The voice of Connecticut’s African Americans rings clear through topics such as the Black Governors of Connecticut, nationally prominent black abolitionists like the reverends Amos Beman and James Pennington, the African American community’s response to the Amistad trial, the letters of Joseph O. Cross of the 29th Regiment of Colored Volunteers in the Civil War, and the Civil Rights work of baseball great Jackie Robinson (a twenty-year resident of Stamford), to name a few.

Over 50 essays by many of the state’s leading historians and edited by Connecticut Explored’s publisher Elizabeth Normen document the long arc of the African American experience in Connecticut from the earliest years of the state’s colonization around 1630 and continuing well into the 20th century. The voice of Connecticut’s African Americans rings clear through topics such as the Black Governors of Connecticut, nationally prominent black abolitionists like the reverends Amos Beman and James Pennington, the African American community’s response to the Amistad trial, the letters of Joseph O. Cross of the 29th Regiment of Colored Volunteers in the Civil War, and the Civil Rights work of baseball great Jackie Robinson (a twenty-year resident of Stamford), to name a few.