by Vivian Zoë

(c) Connecticut Explored, Spring 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

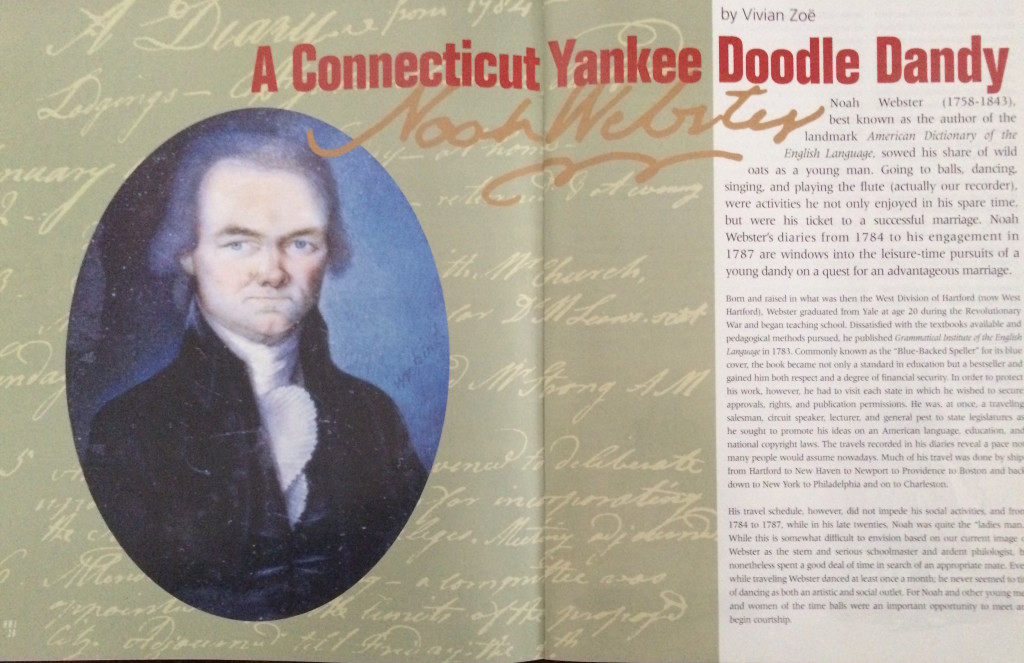

Noah Webster (1758-1843), best known as the author of the landmark American Dictionary of the English Language, sowed his share of wild oats as a young man. Going to balls, dancing, singing, and playing the flute (actually our recorder), were activities he not only enjoyed in his spare time, but were his ticket to a successful marriage. Noah Webster’s diaries from 1784 to his engagement in 1787 are windows into the leisure-time pursuits of a young dandy on a quest for an advantageous marriage.

Noah Webster (1758-1843), best known as the author of the landmark American Dictionary of the English Language, sowed his share of wild oats as a young man. Going to balls, dancing, singing, and playing the flute (actually our recorder), were activities he not only enjoyed in his spare time, but were his ticket to a successful marriage. Noah Webster’s diaries from 1784 to his engagement in 1787 are windows into the leisure-time pursuits of a young dandy on a quest for an advantageous marriage.

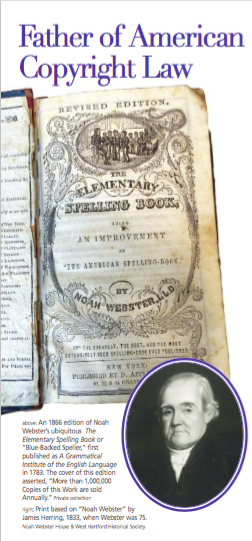

Born and raised in what was then the West Division of Hartford (now West Hartford), Webster graduated from Yale at age 20 during the Revolutionary War and began teaching school. Dissatisfied with the textbooks available and pedagogical methods pursued, he published Grammatical Institute of the English Language in 1783. Commonly known as the “Blue-Backed Speller” for its blue cover, the book became not only a standard in education but a bestseller and gained him both respect and a degree of financial security. In order to protect his work, however, he had to visit each state in which he wished to secure approvals, rights, and publication permissions. He was, at once, a traveling salesman, circuit speaker, lecturer, and general pest to state legislatures as he sought to promote his ideas on an American language, education, and national copyright laws. The travels recorded in his diaries reveal a pace not many people would assume nowadays. Much of his travel was done by ship: from Hartford to New Haven to Newport to Providence to Boston and back down to New York to Philadelphia and on to Charleston.

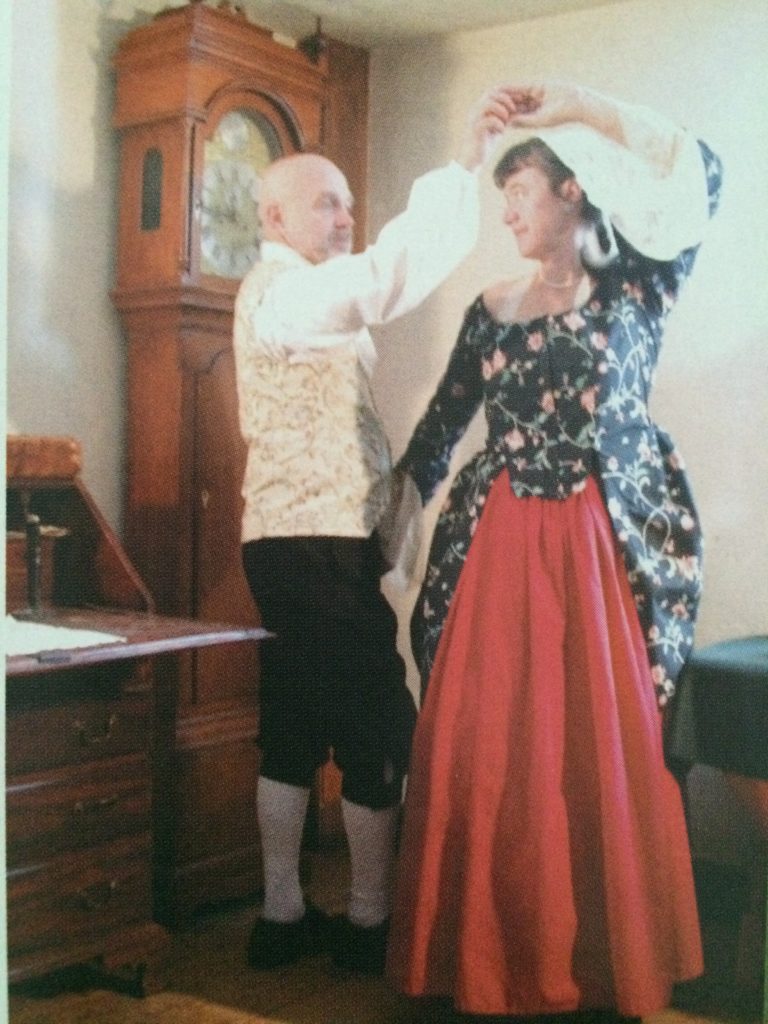

His travel schedule, however, did not impede his social activities, and from 1784 to 1787, while in his late twenties, Noah was quite the “ladies man.” While this is somewhat difficult to envision based on our current image of Webster as the stern and serious schoolmaster and ardent philologist, he nonetheless spent a good deal of time in search of an appropriate mate. Even while traveling Webster danced at least once a month; he never seemed to tire of dancing as both an artistic and social outlet. For Noah and other young men and women of the time balls were an important opportunity to meet and begin courtship.

The term “ball” seems to have been used interchangeably to describe a formal dance as well as an impromptu gathering where dancing was the draw. A ball was even held one week after George Washington’s death to celebrate his life with dance. First and foremost, 18th-century balls were, in addition to social occasions, opportunities to see and be seen: people mingled, caught up on news, transacted business, talked politics, etc.

Noah Webster’s diaries reveal that Hartford was a “hopping” place back then. His Yale connections and his growing respectability as a schoolmaster, writer, publisher, and scion of a politically important family were his entrée to many balls and musical gatherings. In addition, Noah was a member of and mixed socially with the Hartford Wits, a literary group whose members included Jonathan Bull, Oliver Ellsworth, Jeremiah Wadsworth, John Trumbull, Lemuel Hopkins, Samuel Wyllys, and Thomas Seymour. Thus, he danced at one fine Hartford home or another, or at the original State House (a wooden structure on the site of the current Old State House), which was often used for such activities. In early September 1784 Noah attended the equivalent of a singalong there. Shortly after his 26th birthday in October 1784, Noah hosted a ball in Hartford and was afterward very pleased at having “had a brilliant Assembly and an agreeable evening.” His New Year’s celebration that year made him “feel exceedingly well after dancing.”

Much of this time was also spent pining after numerous ladies whom he met through mutual friends. Women come and go in his diaries and he made frequent but verbally economical assessments of their virtues. On March 25, 1784 he recorded: “In the evening saw a multitude of pretty faces. But my heart is my own.” A few weeks later, he wrote: “Read a little, loitered some, had some company, and visited the Ladies in the evening as usual. If there were but one pretty Girl in town, a man could make a choice—but among so many! One’s heart is pulled twenty ways at once. The greatest difficulty, however, is that after a man has made his choice, it remains for the Lady to make hers.” (Emphases, here and elsewhere, are found in transcriptions.)

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire in June 1784, a busy day was recorded thus: “Took a view of the town. Drank tea at Dr. Bracketts [sic]. At evening, attended a ball and was agreeably entertained; had a fine partner, but she is engaged.” Back in Hartford that October, an entry states that he “Learnt a song of the Ladies, a sweet Country life. Drank tea with Miss Polly Sheldon.” The next day, he “rode out with the Ladies. Miss McCurdy, Miss Field and Miss Stoughton—.” And a week later, on October 16, 1784, the entry reads: “My birthday. 26 years of my life are past. I have lived long enough to be good and of some importance. Introduced to Miss S. Dwight of Springfield, a fine Lady.” On October 21, “Miss J. M(c)Curdy leaves town the regret and tears of her friends show how much she is loved.… Such sweetness, delicacy, and beauty are rarely united. May I ever love her; for heaven is her friend.” But two years later, perhaps frustrated with his lack of success, he was less kind, “Introd [sic]to Miss Yates; take tea with Miss Ray… a ten thousand pounder, Miss Ten Broeck.…”

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire in June 1784, a busy day was recorded thus: “Took a view of the town. Drank tea at Dr. Bracketts [sic]. At evening, attended a ball and was agreeably entertained; had a fine partner, but she is engaged.” Back in Hartford that October, an entry states that he “Learnt a song of the Ladies, a sweet Country life. Drank tea with Miss Polly Sheldon.” The next day, he “rode out with the Ladies. Miss McCurdy, Miss Field and Miss Stoughton—.” And a week later, on October 16, 1784, the entry reads: “My birthday. 26 years of my life are past. I have lived long enough to be good and of some importance. Introduced to Miss S. Dwight of Springfield, a fine Lady.” On October 21, “Miss J. M(c)Curdy leaves town the regret and tears of her friends show how much she is loved.… Such sweetness, delicacy, and beauty are rarely united. May I ever love her; for heaven is her friend.” But two years later, perhaps frustrated with his lack of success, he was less kind, “Introd [sic]to Miss Yates; take tea with Miss Ray… a ten thousand pounder, Miss Ten Broeck.…”

Webster was also an accomplished singer and recorder player. Describing his pleasure in the “flute” he wrote: “And what a wise and happy design in the organization of the human frame that the sound of a little hollow tube of wood should dispel in a few moments—the heaviest of cares of life!” He opened several informal and short-lived singing schools during his travels. Some of his schools lasted months and others for the short time of a book-tour visit, which was the case at several churches in Baltimore and Charleston. He clearly loved to sing, thought highly of his abilities, and loved to hear good singing as well. Earlier, as a schoolmaster in Sharon, Connecticut, he started a weekly singing school in a rented space but was rebuffed by a female student who had an interest in another young man. Noah was so affected by the rejection that he abruptly ended the school and left town!

At 18th-century balls, the display and scrutiny of human pulchritude was deliberate and studied. It was critical to have abilities that would not falter under the gaze of friend or foe. Noah Webster must have cut a pretty rug because he met his beloved future wife of 53 years while dancing. It happened when he was on a stop in Philadelphia during a tour to promote the Blue-Backed Speller. Rebecca Greenleaf of Boston was visiting one of her sisters. Rebecca’s family was of a class above Noah’s humble financial origins. Her father was a Boston merchant, property owner, and celebrated patriot. The family, originally of French Huegenot descent “Vertefeuille,” once owned Nantucket Island. By contrast, Noah’s father was a farmer with a relatively small farm of 90 acres. But Noah Sr. also had prestige as a pious deacon, justice of the peace, and lieutenant in the town militia. Noah’s Yale education, coupled with the music and dance taught to him first by his mother and later most certainly by a dancing master, brought him into contact with Rebecca. Though he feared her parents would not accept him, he seems to have endeared himself with good manners, looks, worldliness, and charm.

Shortly before his 28th birthday in October 1786, Noah Webster made a passing reference in his diary to “Miss Greenleaf,” but it was not until the following May that Cupid’s arrow hit its mark. Whether this reflects the general pace of life in 18th-century Hartford or the everpredictable pace of the male sensibility, we can only conjecture. Upon recognizing his feelings, his path was immutably set. Apparently there was abundant reason for this: Miss Greenleaf reportedly turned heads wherever she went.

After meeting Rebecca Greenleaf, it is clear from his diaries that Noah wished to spend as much time with her as she would welcome and proximity would allow. On May 9, 1787 his diary tells us that he was “With the most lovely.” On June 7, he “Visit[ed]the best of women”; on June 22, he recorded that he “Visit[ed]my best friend.”

James Greenleaf, Rebecca’s brother who lived in the Hague, was Noah’s confessor regarding his feelings toward “Becca.” Noah kept James apprised of his efforts to become a successful publisher and attorney through frequent correspondence. From Hartford on September 20, 1789, he admonished James thus, “You will perhaps smile to see how a young lover will muster arguments on the side of his inclinations. But reason in vain opposes my wishes, it is better then to let reason & passion go together. If there ever was a woman, moulded [sic]by the hand of nature to bless her friends in all connections, it is your sister B. To be united to her is not mere pleasure and delight with social advantages, it is a blessing. The man who loves her, loves the temper of saints, and by associating with her, must become a better man, a better citizen, a warmer friend. His heart must be softened by her virtues, his benevolent & tender affections must be multiplied. In short, he must be good, for he would be in some measure, like her. It is vain to keep us asunder. Our hearts are inseparably united, & could you be a witness to our attachment, you would wish our hands united also….”

Despite this devotion, Noah kept company with other young ladies when Becca returned to Boston in June 1787. He spent time with a Miss Donaldson and “the beautiful Miss Peggy Caldwell” and danced with Miss Loudons on Long Island in October. When he finally recognized his deep feelings for Rebecca, no other woman would do.

Without a gift of $1,000 from James Greenleaf, however, Noah probably would have had to wait even longer than the two years of their courtship to marry Rebecca. On the wedding date, October, 26, 1789, Noah entered into his diary, “This day I became a husband. I have lived a long time a bachelor, something more than thirty-one years. But I had no person to form a plan for me in early life & direct me to a profession. I had an enterprising turn of mind, was bold, vain, inexperienced. I have made some unsuccessful attempts, but on the whole hav [sic]done as well as most men of my years. I begin a profession, at a late period of life, but have some advantages of traveling and observation. I am united to an amiable woman, & if I am not happy, shall be much disappointed.”

Noah and Rebecca were married in Boston. Only days after, they left that city to set up housekeeping in Hartford, with the funds from Rebecca’s brother James. Almost immediately, Rebecca fell ill with the flu, which had laid Noah low only days before the wedding. It was another month, at the first official federal “Thanks Giving” holiday that he brought his bride back to the West Division to the farmhouse on Main Street to meet his mother and family. The majority of Noah’s diary references that describe his attending a dance or a ball occur between 1784 and 1789, prior to his marriage to Rebecca. However, after their wedding, he occasionally notes his attendance at balls such as the one he attended on “One of the Coldest days of the Winter”—February 28, 1793. But home life with Becca seemed to suit him best and despite his scholarly and serious image in the world of men, letters, and government, he was a devoted family man. He promised Rebecca’s brother and father that he would abandon the risky business of publishing and commit to a more lucrative and dependable law career. And this he did for a time, but his interests were wide ranging and his traveling continued. In later years he pursued numerous publishing endeavors, including school books, histories, two pro-Federalist newspapers, the Spectator and the Commercial Advertiser, abolition pamphlets and flyers, political treatises, books on public health, and, of course, dictionaries. But having captured his heart’s prize, Noah turned away from a dandy’s pursuits and semi-retired his dancing shoes.

Noah and Rebecca were married in Boston. Only days after, they left that city to set up housekeeping in Hartford, with the funds from Rebecca’s brother James. Almost immediately, Rebecca fell ill with the flu, which had laid Noah low only days before the wedding. It was another month, at the first official federal “Thanks Giving” holiday that he brought his bride back to the West Division to the farmhouse on Main Street to meet his mother and family. The majority of Noah’s diary references that describe his attending a dance or a ball occur between 1784 and 1789, prior to his marriage to Rebecca. However, after their wedding, he occasionally notes his attendance at balls such as the one he attended on “One of the Coldest days of the Winter”—February 28, 1793. But home life with Becca seemed to suit him best and despite his scholarly and serious image in the world of men, letters, and government, he was a devoted family man. He promised Rebecca’s brother and father that he would abandon the risky business of publishing and commit to a more lucrative and dependable law career. And this he did for a time, but his interests were wide ranging and his traveling continued. In later years he pursued numerous publishing endeavors, including school books, histories, two pro-Federalist newspapers, the Spectator and the Commercial Advertiser, abolition pamphlets and flyers, political treatises, books on public health, and, of course, dictionaries. But having captured his heart’s prize, Noah turned away from a dandy’s pursuits and semi-retired his dancing shoes.

In keeping with Noah’s avocation, Colonial and Federal dance, song, and instrumental music are a mainstay at the Noah Webster House in West Hartford, a museum known for its participatory activities, particularly for children. The Webster Company, the museum’s 18th-century dance and music group, was recently included in the Connecticut Commission on the Arts Performing Artists Roster and performs at festivals throughout Connecticut and New England.

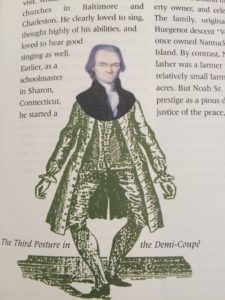

The museum is guided by the work of Kate Van Winkle Keller and Charles Cyril Hendrickson, 18th-century American dance scholars who have written numerous books and articles on the subject. Keller’s research reveals that between the urban centers of New York and Boston, in areas such as Litchfield and Hartford, itinerant dancing masters advertised in local journals and were able to make a living traveling from town to town around the state. The masters taught dance to young people eager to meet and be well perceived by members of the opposite sex.

What is difficult to portray today is the social essence of dance in the 18th century. A gavotte under the watchful eyes of elders was the most common method of meeting appropriate potential mates. Because the minuets, gavottes, and allemandes were performed generally by a couple, unlike individual reels and jigs and group country dances, they required the instruction of a dancing master. Lest the “performers”

embarrass themselves attempting the very conventionalized steps of a minuet, while under observation by the object of their desire, practice and instruction was necessary. Such is the job of present-day Webster Company Dance Mistress Helen Davenport-Senuta, a scholar and practitioner of early American and English Country Dance and Music. She takes a diverse crew of men, women, and youth and forms them into an elegant party of fine Colonial- and Federal-era hoofers.

While performances by the Webster Company are accompanied by onlookers, they are rarely elders. Today, a gathering is best described as the sudden appearance of an incongruous group of anachronists of all ages. Audiences are always asked to join in, and, with few exceptions, crowds are eager to abandon their 21st-century inhibitions.

Vivian F. Zoë was the executive director/curator of the Noah Webster House in West Hartford.

Explore!

Noah Webster, Father of American Copyright Law, Fall 2014

Noah Webster Slept Here. And So Did I, Winter 2005/2005

The Iceman Cometh (And Goeth), Spring 2019