By Elizabeth J. Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Noah Webster, born in Hartford (now West Hartford) in 1758, understood the power of the pen and the power of language—specifically a uniquely American language. As former Noah Webster House director Chris Dobbs has noted, Webster saw his An American Dictionary of the English Language (first published in 1828) “as being more than a convenient reference; he regarded its contributions to standardized language usage and spelling as integral to building a new nation.” (See connecticuthistory.org/noah-webster-and-the-dream-of-a-common-language.)

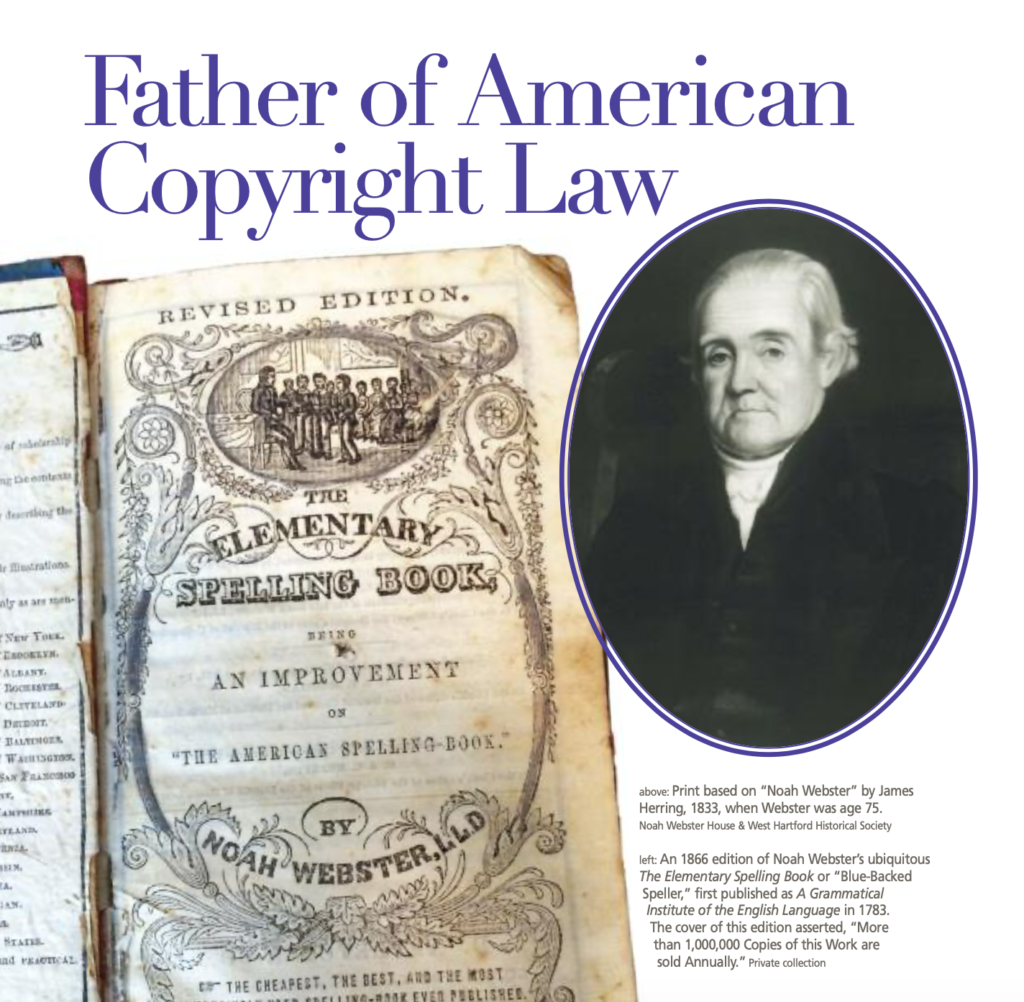

Webster was also a political activist, a newspaper editor, a founder of Amherst College, and an early antislavery advocate. But it was his work as a teacher and an education reformer—work he realized in large part through his best-selling “Blue-Backed Speller”—that also earned him his reputation as “father of American copyright law.” Connecticut played a role, too, in establishing the law that served as the basis for today’s copyright standards.

In 1782, as Webster prepared to publish the first volume of A Grammatical Institute of the English Language (a.k.a. the Blue-Backed Speller, published in 1783), the fledgling United States had yet to enact its own copyright laws. Webster travelled to Philadelphia to lobby the Continental Congress to take action. As Harlow Giles Unger relates in Noah Webster: The Life and Times of An American Patriot (John Wiley & Sons, 1998):

Outside Independence Hall, [Webster] collared such powerful men as New York’s James and Robert Livingston and Virginia’s James Madison and Thomas Jefferson. All approved Webster’s scheme for a national system of instruction and agreed to support copyright protection, but, they pointed out, the Articles of Confederation gave Congress no power to enact, let along enforce, such a law. The Congress could only resolve to recommend that each of the states pass its own copyright legislation.

Congress did pass such a recommendation in May 1783. In the meantime Webster set out to petition each state. Connecticut was first to act. According to the United States Copyright Office (copyright.gov/history/dates.pdf), in January 1783 “the earliest copyright statute in the United States was passed by the General Court of Connecticut under the title ‘An Act for the Encouragement of Literature and Genius.’ Dr. Noah Webster, famed lexicographer and one of Connecticut’s most distinguished men, was directly instrumental in securing its enactment.” But William F. Patry, in “Copyright Law and Practice” (The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc., 1994, 2000 accessed at digital-law-online.info/patry/patry3.html), asserts that credit goes to another: “On January 6, 1783, John Ledyard, the author of A Journal of Captain Cook’s Last Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, petitioned the Connecticut General Assembly for copyright protection. On January 29, 1783, the General Assembly, instead of passing a private bill for Ledyard [as had been the custom before such blanket legislation was enacted], passed the first general colonial copyright statute.” As Webster had been lobbying the legislature since 1782, it seems likely that he, too, influenced the passage of the bill. Later that year, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island passed statutes, followed by Pennsylvania and South Carolina in 1784; many of those laws were based on Connecticut’s, according to Patry—and their passage influenced by Webster’s having lobbied many of the state legislatures, according to Unger.

In early 1785 and with his speller a success in New England, Webster put the finishing touches on volume two, a “reader,” and planned for expansion into the South. According to Unger, “He would visit the legislatures, petition for copyright protection, then travel from town to town, introducing his [speller]to instructors, churchmen, and men of influence.” As a result of Webster’s and others’ lobbying, in 1785 and 1786, North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and New York also enacted legislation.

The Constitution sent to the states to be ratified in 1787, included a clause granting Congress the power to enact federal copyright law. The first copyright bill, which Patry notes may have been based on a draft by Noah Webster, was submitted to Congress by Connecticut’s Benjamin Huntington in 1789, but it was not acted on. After several bills were considered, the first federal copyright law was enacted in 1790.

In 1831, Webster, now in his 70s, was still at it. The first major revision of the federal law was enacted that year, introduced by Congressman William W. Ellsworth of Connecticut, son of Oliver Ellsworth, the third chief justice of the Supreme Court and Webster’s son-in-law. At Webster’s urging, the revision extended protection from 14 years to 28 years; Unger notes that Webster actively lobbied for its passage. The 1831 law prevailed, largely intact, until 1909. Webster’s activism in education, language, political, and copyright reform was tireless and unquestionably influenced the course of the new nation.

Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

“Noah Webster: A Connecticut Yankee Doodle Dandy,” Spring 2003

“Noah Webster: Accent on an American Language,” Spring 2005

“A Way with Words,” Winter 2020-2021

Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

227 South Main Street, West Hartford

noahwebsterhouse.org