(c) CT Explored, Spring 2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Everyone remembers the famous 1980s ad campaign by candy giant Peter Paul, Inc., “Sometimes you feel like a nut, sometimes you don’t,” which referred to the company’s two most popular candies, Mounds and Almond Joy. By the 1980s, Peter Paul, Inc. was a giant in the industry, with annual net sales topping $70 million. It had come a long way from its humble beginnings as a small-town confectionery shop in Naugatuck, Connecticut. How that shop evolved into a nationally prominent corporation, weathered the Great Depression, and endured the supply shortages of World War II to become the manufacturer of some of the best known candy bars in the world is a genuine American-dream story.

The story begins with the confections of Peter Halajian. Born in Armenia in 1864, he came to the United States in 1890 and began working in one of Naugatuck’s thriving rubber factories. His job was flexible enough that once he reached his quota for the day (often by early afternoon) he was free to spend time on other activities. An ambitious and enterprising man, he dreamed of being self-employed and began operating a fruit and candy business with his two daughters, May and Lillian. Halajian and the girls would sell their homemade sweets door-to-door around Naugatuck and to commuters at the train stations up and down the Naugatuck Valley. The demand for his products spread as he gained a reputation for supplying quality sweets. After five years, he achieved his dream of being a business owner. On February 1, 1895 he opened a candy and ice-cream shop on Water Street in Naugatuck, not far from the bustling rubber factories and the town center. Halajian sold a variety of items including lemon drops, peanut brittle, licorice, various chocolates, caramels, and assorted ice-cream flavors. His sweets were a delicious sensation, and within a short time he opened a second shop, this one in Torrington, where his brother lived. Because customers found it hard to pronounce his Armenian surname, Halajian legally changed it to the English equivalent, Paul. Around the turn of the century, he began advertising, using clever slogans in local newspaper ads and distributing handbills to potential customers.

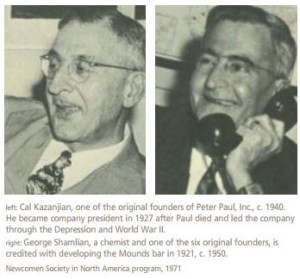

In 1912, Peter Paul opened a third shop, his second in Naugatuck. Around this time Cal Kazanjian, Paul’s brother-inlaw, became associated with the business. Cal had come to the United States from Armenia with his father, a Congregational minister, a decade before. Cal became increasingly involved in the business as a worsening arthritic condition limited Paul’s personal attention at the shops.

The small chain of sweets shops prospered through World War I, and Paul and Kazanjian dreamed of expanding the operation beyond small-town candy kitchens. During the war, the U.S. Army commissioned various American candy manufacturers to provide chocolate for the doughboys in Europe. As a high-energy food that would last for long periods of time in the trenches, chocolate bars became a comforting staple. The troops eventually returned home, and, as civilians, wanted more of the same. The American candy-bar business was assured, and the two enterprising men wanted to become part of the emerging industry. Their dreams, however, would take the ambitions, and the money, of more than just two men. In 1919 they convinced four other close friends and relatives to pool their resources and go into the candy business on a much larger scale.

Their firm was established as the Peter Paul Manufacturing Company. According to the National Confectioners Association, it was one of an estimated 6,000 candy companies that began production between the World Wars. Since that time, tens of thousands of candy-bar varieties have been introduced in the United States. Today, fewer than 300 companies manufacture the vast majority of candy in the America, with the shelves dominated by a few corporations.

From those first days grew a philosophy that guided The Peter Paul Manufacturing Company to quickly prosper and continually expand, separating them from the thousands of failed firms: Give customers fresh, quality candy and top value for their money. These core values allowed the company to survive the ruthless candy competition of the 1920s. Even more remarkably, while thousands of small businesses were closing their doors or cutting quality in the 1930s, Peter Paul prospered beyond even its founders’ sweetest dreams.

All of the original founders and first stockholders were, like Paul and Kazanjian, Armenian immigrants. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of Armenians came to the United States to escape persecution and horror in their native land. Even as their country was part of the multinational Ottoman Empire, the Armenian people were determined to maintain their own traditions. Christians in a mostly Muslim state, the Armenians became targets of physical extermination by their Turkish rulers. Violence and forced deportations caused thousands to emigrate to the United States. Many came to Connecticut for education and job opportunities, carving out small ethnic enclaves in Hartford, New Haven, Bridgeport, and throughout the Naugatuck Valley.

The six founders s of The Peter Paul Manufacturing Company were a tightknit group, and the company would retain a family atmosphere throughout its history. Paul became the company’s first president; George Shamlian, a former chemist with Naugatuck Chemical, became vice president, and Kazanjian became secretary/treasurer. Kazanjian would also be responsible for setting up a sales organization of commission brokers; finding retailers willing to sell the products of a new company was a daunting task. Cal’s cousin Artin Kazanjian and Jacob Chouljian became foremen of operations, and Chouljian’s cousin Jacob Hagopian became assistant treasurer. Chouljian would later marry one of Cal Kazanjian’s sisters, strengthening the feeling of family in the company. These six men risked a total of $6,000 (roughly $66,000 today) on opening a company in the emerging candy-manufacturing-business. The new company began production in November 1919 in a 50-by-60-foot loft on Webster Street in New Haven. With no refrigeration system, they made the candy at night and shipped it out the next morning while it was still fresh. At first, they manufactured a line of confections not too different from what other manufacturers offered: a coconut-cream bar, peanut brittle, candy kisses, and lollipops.

The owners, however, knew that to succeed in the long run, they needed to differentiate themselves from the competition. They hired Harry Tatigian, an experienced candy maker from Bridgeport, to help develop some unique products to set The Peter Paul Manufacturing Company apart. The first really distinctive product the company produced was the Konabar, a chocolate-covered blend of coconut, nuts, and fruit. The new product was a relative success, but nobody could have imagined the changes that were coming.

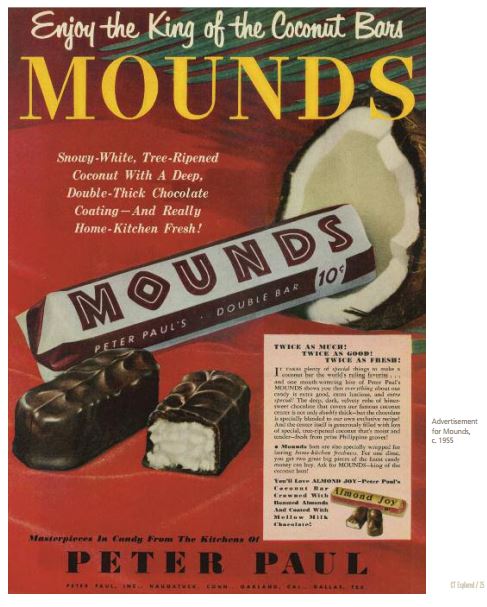

The product that would make Peter Paul a household name was the Mounds candy bar, introduced in 1921 with the same combination of snowy-white coconut and dark chocolate we enjoy to this day. Developed by Shamlian and Tatigian, it was an instant sensation and would remain the company’s best-selling and most popular product throughout its long history. Mounds was such a success that production could barely keep up with demand, especially since the work was so tedious. Each bar was individually rolled, flattened, shaped, dipped in chocolate, and wrapped in foil, all by hand.

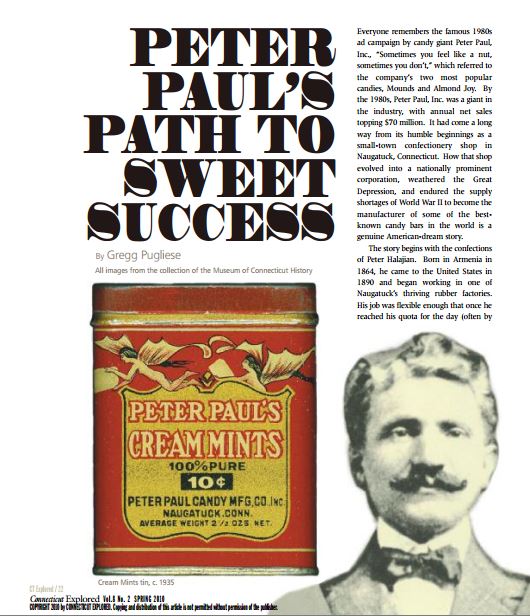

By 1922, the business had grown to such an extent that it needed more space and new machinery. Cal Kazanjian approached the company’s New Haven bank for an investment loan, but this request was refused. The bank believed that the candy business was already too crowded, which made The Peter Paul Manufacturing Company too much of a risk. A more fore-sighted Naugatuck bank, however, through the efforts of the local Chamber of Commerce, agreed to make the loan, and the company moved to Naugatuck, where it had its roots with Paul’s original candy shop. On a spacious hillside on the road to Bethany, away from the grimy industrial heart of the rubber factories, the company erected a new plant for $35,000 in 1922 and faced the future with a renewed sense of optimism. The thriving company also broadened its line to include new items such as the Smile-Awhile (a peanut roll with a caramel center), Bachelor Bars (featuring sesame seeds), Thin Mints, and after-dinner mints. The expansion quickly paid off; it took the company only two years to repay the loan in full, with interest.

In 1927, Peter Paul, who had been in poor health for sometime, died, and Cal Kazanjian was named president. He would remain in that position until his own death in 1948, leading the company through the Great Depression and the challenges of dealing with shortages of raw materials during World War II.

In 1927, Peter Paul, who had been in poor health for sometime, died, and Cal Kazanjian was named president. He would remain in that position until his own death in 1948, leading the company through the Great Depression and the challenges of dealing with shortages of raw materials during World War II.

In1929 the company made its first acquisition, purchasing J.N. Collins Company, a caramel business operating in Minneapolis and Philadelphia. The Peter Paul Manufacturing Company then officially became Peter Paul, Inc.

The popularity of the Mounds bar continued to grow throughout the 1920s, and Peter Paul, Inc. found itself competing with some of the most famous names in the business. Nationally, the biggest competition came from three bars introduced around the same time as the Mounds: The Oh Henry! was introduced in 1920 by the Williamson Candy Company of Chicago, the Baby Ruth in 1921 by the Curtiss Candy Company, also of Chicago, and the Milky Way in 1923 by the Mars Company of Minneapolis.

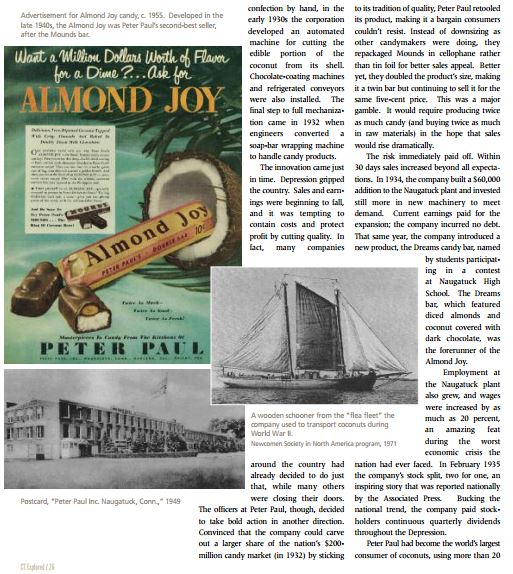

Kazanjian believed in a philosophy of specialization and decided to discontinue most of their other items to concentrate on developing an efficient, low-cost way to produce Mounds. Recognizing that they could not continue to manufacture the confection by hand, in the early 1930s the corporation developed an automated machine for cutting the edible portion of the coconut from its shell. Chocolate-coating machines and refrigerated conveyors were also installed. The final step to full mechanization came in 1932 when engineers converted a soap-bar wrapping machine to handle candy products.

handle candy products. The innovation came just in time. Depression gripped the country. Sales and earnings were beginning to fall, and it was tempting to contain costs and protect profit by cutting quality. In fact, many companies around the country had already decided to do just that, while many others were closing their doors. The officers at Peter Paul, though, decided to take bold action in another direction. Convinced that the company could carve out a larger share of the nation’s $200- million candy market (in 1932) by sticking to its tradition of quality, Peter Paul retooled its product, making it a bargain consumers couldn’t resist. Instead of downsizing as other candymakers were doing, they repackaged Mounds in cellophane rather than tin foil for better sales appeal. Better yet, they doubled the product’s size, making it a twin bar but continuing to sell it for the same five-cent price. This was a major gamble. It would require producing twice as much candy (and buying twice as much in raw materials) in the hope that sales would rise dramatically.

The risk immediately paid off. Within 30 days sales increased beyond all expectations. In 1934, the company built a $60,000 addition to the Naugatuck plant and invested still more in new machinery to meet demand. Current earnings paid for the expansion; the company incurred no debt. That same year, the company introduced a new product, the Dreams candy bar, named by students participating in a contest at Naugatuck High School. The Dreams bar, which featured diced almonds and coconut covered with dark chocolate, was the forerunner of the Almond Joy.

Employment at the Naugatuck plant also grew, and wages were increased by as much as 20 percent, an amazing feat during the worst economic crisis the nation had ever faced. In February 1935 the company’s stock split, two for one, an inspiring story that was reported nationally by the Associated Press. Bucking the national trend, the company paid stockholders continuous quarterly dividends throughout the Depression.

Peter Paul had become the world’s largest consumer of coconuts, using more than 20 percent of what was imported into the United States. More than 100,000 pounds of candy a day was shipped out of Naugatuck. The town once known as the home of the United States Rubber Company became better known throughout the United States as the home of Peter Paul, Inc.

Radio advertising contributed mightily to the company’s incredible increase in sales in the 1930s. Peter Paul advertised on the nationally syndicated shows of the most popular radio personalities of the time, including Uncle Don, Gabriel Heatter, Bill Slater, and Edwin C. Hill. The company’s popular slogan “What a bar for five cents!” was broadcast across the country, while the “Limpin’ Limerick” contest offered $100 in prizes every week to the 100 best listener-submitted limericks about Mounds and Dreams.

“Any business that doesn’t emerge from the depression stronger than it was when the economic panic began probably has a captain who does not know how to run his ship,” boasted Cal Kazanjian in a 1935 interview published in The Hartford Courant. “Even an amateur can pilot a boat in fair weather. Many businessmen,” he continued, “forget that they are servants of the public and try to dictate to it. If they would take the attitude that they would serve for whatever the public would pay, the public would support them more wholeheartedly, I’m sure.” By the late 1930s both Mounds and Dreams were ranked among the five top-selling candy bars in the United States, and Peter Paul had established its reputation as the company that never knew the Depression.

World War II brought tremendous challenges of a different sort. Early in 1942, Peter Paul lost its entire supply of coconut when the Japanese overran the Philippines. The company had to find new sources in the Caribbean, a task complicated by the German submarines scouring the Atlantic Ocean. Under the assumption that the Germans wouldn’t waste torpedoes on small boats, they bought seven wooden auxiliary schooners to bring coconuts from several small Caribbean islands to processing plants in Puerto Rico and Florida. Soon these vessels, called the “flea fleet,” were supplying the company with its desperately needed raw material. The schooners occasionally reported enemy submarine sightings to the naval authorities but never were targeted by the subs themselves. Peter Paul gave the coconut shells to chemical plants, where they were used to produce activated carbon for gas masks and high explosives.

Sugar rationing and chocolate shortages further complicated the job of manufacturing high-quality candy bars. The management, however, refused to use fillers or substitutes of any kind. Cal Kazanjian pledged, “We will make Mounds the right way, or we will close the company down until we can.” Making Mounds the right way meant discontinuing production of lesser-selling candies such as Dreams, leaving all available coconut, sugar, and chocolate to be used for Mounds.

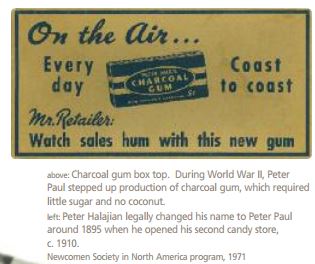

Just as in the First World War, candy became an integral part of an American soldier’s rations. Peter Paul’s major client during World War II was the U.S. military, which purchased as much as 80 percent of the company’s output by 1944. At the height of the war, the company was packing 5 million candy bars monthly into combat rations, with only a limited quantity available for the civilian population. Even as the company stopped producing Dreams, it stepped up production of caramels and charcoal gum, which required little sugar and no coconut, thus maintaining both the volume of its output and its employment rolls during the war.

Victory in the war brought a surge in demand for candy. In 1948, Peter Paul added a new candy bar to replace the Dreams. Almond Joy, with its juicy coconut center, double-toasted almonds, and milk-chocolate coating, was an instant triumph. Just as the company had staked its claim on national radio in the 1930s, Peter Paul led the industry in the use of network television advertising in the early 1950s. The Peter Paul Pixies sang that Mounds and Almond Joys were “Indescribably delicious,” and the entire nation agreed. Later, the company would be the first candy manufacturer to use full-color TV commercials as a perfect medium for showing its products’ irresistible chocolate and coconut.

By the 1970s, the candy business was changing drastically, and larger corporations targeted Peter Paul for acquisition. To avoid a hostile takeover, the company initiated talks with several companies, and, despite objections from many long-time shareholders, Peter Paul, Inc. was sold in 1978 to Cadbury Schweppes, a British firm. Cadbury paid $27.50 per share, or about $58 million. The words “made in Naugatuck” soon faded from the Mounds and Almond Joy labels, although the company remained in Naugatuck and the candies kept rolling off the assembly line. The industry continued to change in the 1980s as the largest firms gobbled up competitors. In 1988, Hershey’s acquired the U.S. operations of Cadbury Schweppes for $300 million, gaining the still extremely popular Peter Paul Mounds and Almond Joy bars.

In April 2007, the Hershey Company announced it would close the Naugatuck plant. For more than 84 years, the Peter Paul plant had churned out delicious candy, but in November 2007 the conveyor belts came to a halt, and operations were moved to Virginia.

It would be tough to find another Connecticut manufacturing company with an equally spectacular career. Nor can many match the company’s successes during the hard times of the Depression and World War II. Peter Paul, Inc., as a purely Connecticut company, has now faded into history, but the memories will forever be “indescribably delicious.”

It would be tough to find another Connecticut manufacturing company with an equally spectacular career. Nor can many match the company’s successes during the hard times of the Depression and World War II. Peter Paul, Inc., as a purely Connecticut company, has now faded into history, but the memories will forever be “indescribably delicious.”

Greg Pugliese teaches history at John F. Kennedy High School in Waterbury. He would like to thank his family and the wonderful people at the Naugatuck Historical Society for all of their help with this article.

Explore!

Read more stories about products and inventions made in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.