(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

Ruth Hovey Allison, a Hartford hero of the First World War, never fired a shot, but her bravery under fire in France was recognized by those at the highest echelons. She was among thousands of American women who, in the military services or as volunteers with service organizations such as the Red Cross and Salvation Army, risked their lives in Europe. A young nurse with a front-line surgical unit, Hovey showed her mettle treating patients nearly non-stop for days, as German shells crashed overhead, during the heavy fighting in July 1918.

“You needn’t worry about me, for we have learned by our recent experience that it is not practical to be so near the firing line,” Hovey wrote her mother afterwards, vividly describing her experience and glowing with patriotic pride over the accomplishments of the doughboys she served. “Our boys certainly have the right stuff! . . . It’s their cocksureness and nerve that makes them good fighters.”

The youngest of three children, Hovey grew up in a large colonial at 714 Prospect Avenue, Hartford, built by her father Henry Russell Hovey, the son and namesake of an Essex sea captain. She graduated nursing school at Presbyterian Hospital in New York City in 1914 and was working at Hartford Hospital in the social service department when the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917.

The 27-year-old Hovey enlisted May 10 and was mobilized at Presbyterian with Base Hospital No. 2, an Army Medical Corps unit being rushed to Europe to meet the urgent medical needs of the British and French. The transport, SS St. Louis, left New York Harbor May 14, 1917. On board were the unit’s 65 nurses, 153 enlisted personnel, and 26 doctors, among whom was a 28-year-old medical officer 1st Lt. Benjamin R. Allison of upstate New York. He and Hovey would marry after the war, and much of what is known of her wartime experience is recorded in Allison’s unpublished memoir based on his wartime diary.

Following a hectic few days of orientation in England, the unit crossed the English Channel on June 1 and was attached to the British Expeditionary Force at Étretat, a lovely resort village northeast of Le Havre. Between 1,000 and 1,500 patients a day were treated at the base hospital there. Shifts could be long and grueling, but there were compensations: good food, pleasant lodgings, and plenty of free time for sightseeing, recreation, and morale-building diversions.

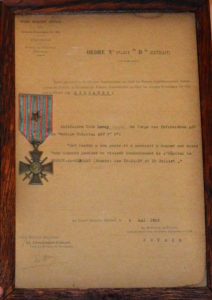

Ruth Hovey’s WWI Victory Medal and service record citation. photo: David Drury, courtesy of Allison Deen

Hovey had been in Étretat for 10 months when the war took a turn after the great German offensive in March 1918. Convoy after convoy brought in the wounded, and doctors and nurses worked day and night readying evacuees. “Our morale was pretty low during the first week as it looked as though nothing would stop the Germans and they would take Paris—then perhaps come our way,’’ recalled Allison. The Allied lines held, and on June 6 Allison and Hovey left Étretat with one of the American Expeditionary Force’s first mobile surgical teams. Hovey and Allison found time for sightseeing around Paris.

In mid-July, while attached to the AEF 42nd (Rainbow) Division, the surgical team was quartered at a French hut hospital at Bussy-le-Chateau, a few miles behind the front lines. In the wee hours of July 15 all hell broke loose with the opening of the Second Battle of the Marne. The Kaiser’s artillery sent shells whizzing over and crashing near the hospital huts. Doctors and nurses leaped from their cots and grabbed gas masks. The nurses sheltered in the dugout, a steel-encased bunker providing safety from artillery fire. Patients were moved into the dugout to clear the wards for the expected flow of casualties, which began arriving within two hours.

The operating room was busy during the ground-shaking, building piercing bombardment. Allison wrote about watching Hovey, an anesthetist, calmly remove her tin helmet to pour ether to sedate patients. A lull in the shelling allowed patients and staff to be evacuated before it resumed again, leaving the hospital in ruins. “The Huns had our range exactly and there is not a doubt but they intended to do as much harm as possible in spite of the four large red crosses we had on our grounds,’’ Hovey wrote her mother. The relocated surgical team continued treating patients almost non-stop, under periods of shellfire, for the next three days.

Hovey experienced a severe bout of pneumonia during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. Allison was by her side, nursing her back to health. In February 1919 the men and women of Base Hospital No. 2 returned home.

Allison and Hovey were married at her parents’ home in Hartford on June 18, 1919. The following month Hovey learned she (along with a small handful of other nurses) was receiving the Croix-de-Guerre with bronze star by order of Marshal Philippe Pétain and approved by General Pershing in recognition of her heroism.

The couple settled in Hewlett, New York. Allison died in 1981 and Hovey in 1986. Hovey’s Croix de Guerre always hung prominently in their home. “She wasn’t shy about that. She was very, very proud,” her granddaughter Allison Deen recalled.

David Drury is a retired Hartford Courant editor and author of Hartford in World War I (The History Press, 2015).

Listen to our podcasts about Connecticut in World War I at Gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com.