(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

By Nicholas F. Bellantoni

On the eve of his retirement, Connecticut Explored invited Nick Bellantoni to reflect on his long tenure as state archaeologist.

Planning for my retirement after 27 years as the Connecticut state archaeologist has allowed me opportunity to reflect back on the contribution of the science of archaeology to the understanding of the history and people of our state. Looking back, I could never have imagined the career and the fascinating projects I (and the students, volunteers, and staff at the Museum of Natural History who have assisted me) have been involved with over the years. After all, the average person might not consider Connecticut the Archaeological Capital of the World! Nonetheless, wherever people have lived on the land, developed shelters and work spaces, raised their families, adapted to the environment, developed technologies and marketplaces, and exploited the natural resources around them, they have left tangible evidences of existence in the form of material culture, and many times those remains are underground. In New England, that history extends back more than 10,000 years.

History and archaeology are the only sciences that address the understanding of past human conditions. Though their methodologies differ, the two disciplines’ interpretations of the written word and material culture (i.e., artifacts) together represent the totality of what we will ever know about our collective and individual pasts. Historians use primary written documents, conducting “archaeological” investigations within the corridors of libraries where inscribed archives survive. Archaeologists use the spatial contexts (both horizontal and vertical) of artifacts and features often hidden underground to interpret the past. Archaeology can be used to corroborate history, but it is probably the most fun when it alters history. Whichever it does, it completes history because the two approaches contribute to the end result: learning all we will ever learn about our past.

Archaeology is inclusive. Everyone’s past is represented in the archaeological record, even those who did not contribute to the written record or did not have their accounts told in views expressed by their own cultures and traditions. Native Americans, disenfranchised Euro-Americans, African Americans, and I suspect, before long, Asian Americans and Hispanics have and will find their Connecticut stories told through archaeological investigations. All of our collective ancestors have left behind artifacts and archaeological sites, and these places and things tell of human survival, adaptation, and continuity.

Archaeology is inclusive. Everyone’s past is represented in the archaeological record, even those who did not contribute to the written record or did not have their accounts told in views expressed by their own cultures and traditions. Native Americans, disenfranchised Euro-Americans, African Americans, and I suspect, before long, Asian Americans and Hispanics have and will find their Connecticut stories told through archaeological investigations. All of our collective ancestors have left behind artifacts and archaeological sites, and these places and things tell of human survival, adaptation, and continuity.

Interpretation of the past is not abstract or esoteric. How it is interpreted has significant import to descendants and people searching for meaning in their lives today. The past gives us a sense of identity, self-esteem, and community. It should contribute to the quality of our lives. As humans, we are connected to those who have come before us, through their struggles, hopes, and aspirations. We honor them by studying their lives. They honor us by giving us life.

Looking back over my tenure, the names of a number of historical people stand out most prominently: Henry Opukaha’ia, the first Christianized Native Hawaiian; Henry Chauncey, Middletown business man and co-builder of the Panamanian railroad; Samuel Huntington, signer of the Declaration of Independence and 10-term governor of Connecticut; John Brown, abolitionist and Torrington native; Peter Pond, 18th-century Mountain Man; Albert Afraid of Hawk, Oglala Lakota, who died in Danbury while performing with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show [see page xx]; Old Leatherman, and Lt. Eugene Bradley, who in 1941 became the first person to die at the Windsor Locks Army Air Base, among many, many others.

I have come to know several of these individuals personally by conducting forensic examinations of their skeletal remains, which have provided insights into their life histories, including aspects of their health and life stress pathologies. Forensic archaeology/anthropology gives us a unique view of past life histories as recorded in the hard tissue of our bones. It gets very personal as you come to know people in ways that can never be understood through written words or artifacts alone.

Looking back, multiple projects conducted by our office and other Connecticut archaeologists through the years are memorable, and to discuss only a few will omit so many compelling and interesting stories. Nonetheless, as evidence of the cultural diversity and contribution of our science, I present a select few of my favorite examples of historical and archaeological research in our state:

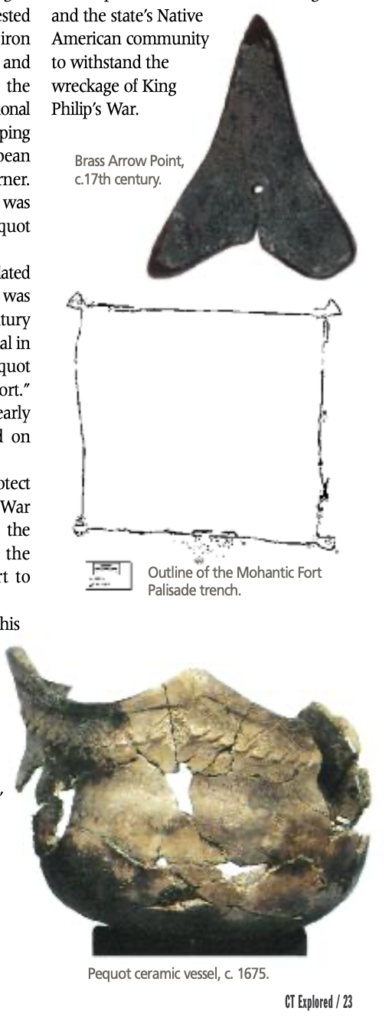

New England Hebrew Farmers of Emanuel Society Site

In 1890, Baron de Hirsch, a wealthy railroad construction tycoon, funded the development of a farming community in the remote village of Chesterfield in Montville, Connecticut. His conceit and philanthropy was to provide an opportunity for Jews living in the congested Lower East Side of Manhattan to leave the city and live healthier lives in rural areas, away from the disease and poverty of their urban experience. The Chesterfield community would be the first of a number of settlements where Jewish families would relocate and establish dairy farms throughout the state and region. Life was not easy for these settlers, who had little farming experience and had to contend with the cold weather and Connecticut’s hard rocky land. But, persist they did into the 20th century, establishing a synagogue as their religious center and later selling their dairy products through a central creamery funded by Baron de Hirsch. Spiritual needs were also attended to by establishment of a residence for the ritual slaughterer, or “shochet,” and the maintenance of a mikveh, a ritual bath that was essential for traditional Jewish married life. Built by 1910, the mikveh was a surprising find in this rural Hebrew community. By the late 19th century, rabbis across the country were complaining about the decline of traditional religious practices, especially the lack of ritual bathing. With assimilation of East European Jews into American life and the development of the reform movement, many communities were disinclined to maintain a mikveh. No others had been found in Connecticut. However, there it was in Chesterfield.

According to Jewish laws, husband and wife can resume marital relationships only after the wife immerses in a mikveh following a seven-day waiting period after the cessation of her menstrual flow. In addition, it is customary for the bride and groom each to immerse in advance of their wedding day, and for men to bathe prior to the high holy days. Immersion in a mikveh is also mandatory for conversion to Judaism.

According to Jewish laws, husband and wife can resume marital relationships only after the wife immerses in a mikveh following a seven-day waiting period after the cessation of her menstrual flow. In addition, it is customary for the bride and groom each to immerse in advance of their wedding day, and for men to bathe prior to the high holy days. Immersion in a mikveh is also mandatory for conversion to Judaism.

Building on the original archaeological surveys conducted by the Archaeological & Historical Services, Inc., and Historical Perspectives, Inc., the Office of State Archaeology, in partnership with the Center for Judaic Studies and Contemporary Jewish Life at the University of Connecticut, conducted an archaeological field school that focused on the shochet’s house, where the mikveh was located. What is striking about this bath is that it is unlike any modern, tiled mikveh. The Chesterfield bath is constructed of concrete and in this sense reminds one of the ancient ritual baths in Israel, which were made of stone and lined with plaster.

Archaeological excavations demonstrated that the Chesterfield mikveh was wood-lined, which was somewhat of a surprise, since Talmudic law forbids the use of wood within a mikveh construction. It turns out, however, that there is a medieval tradition, stemming from some European communities, of using wood. Also, our excavation traced the source of the water for the bath. Mikveh water has to come from the heavens, or from the ground. It cannot be interfered with by human hands but must be derived directly from God. The archaeologists traced a water pipe eastward toward Power’s Pond across the street, and we suspect that the water came from a nearby, natural stream. Gravity apparently caused the water to flow through the pipes to the mikveh without any human interference. Behind the house, numerous cattle and chicken bones were discarded. These skeletal elements are being analyzed to see if they were slaughtered according to established written traditional Jewish dietary laws.

Archaeology has contributed greatly to this one-of-a-kind discovery. In the words of Stuart Miller, co-director of the archaeological field school, “At every step [of the excavations], we were finding something I didn’t expect to find.”

Read more:

Hebrew Tillers of the Soil

Faith Amidst the Fields, Winter 2010-2011

The Monhantic Fort, Mashantucket Pequot Reservation

Before any economic development projects are begun on the Mashantucket Pequot or other Indian reservations in Connecticut, complete archaeological surveys are conducted to ensure that any significant historical sites will not be adversely affected. An archaeological survey on the Pequot Reservation in 1991, in preparation for construction of a utility storage building, yielded a number of Pre-Contact and historic artifacts in the initial test pits. Unexpectedly, a curious dark linear stain in the soil repeatedly appeared. Not understanding whether the soil stain represented a natural or cultural deposit, Kevin McBride, director of research with the tribe’s museum, pondered its meaning for days. Then, it struck him. Could the stain be the belowground remnant of a palisade, a fort? There were no historic records to suggest a fort had existed on the Pequot Reservation. Following the linear stains, which ran perpendicular to each other, the archaeological crews found a triangular configuration at their junction resembling a small bastion designed to protect a fort’s walls from attack.

More intensive archaeological investigations determined that the “fort” was roughly square, measuring 170 feet by 190 feet. Excavations yielded artifacts dating to the late 17th century. Soil stains suggested the construction of wigwams and an iron forge where firearms were repaired and musket balls manufactured inside the stronghold. The fortification had a traditional Native American entrance of overlapping palisade walls; otherwise, it was European in design, with bastions at each corner. If this was indeed an Indian fort, what was it doing on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation?

The archaeological discovery stimulated further historic research. An item was located in the journal of a 17th-century magistrate, telling of a colonial official in Hartford planning a trip to visit the Pequot sachem “Robin Cassasinamon, at his fort.” It is the only recorded reference to an early historic military fort’s having existed on the Indian reservation.

The Monhantic Fort was built to protect the Pequot during King Philip’s War (1675-1676). Fearful of attack by the Narragansett tribe, the Pequot built the fort to defend the colony’s eastern front. While this Indian uprising, meant to purge New England of the intrusive English settlements, was devastating to the other English colonies, Connecticut was relatively unaffected due to its alliances with the Mohegan sachem Uncas and with the Pequot.

The Mohantic Fort Site is now listed as a National Historic Landmark. No one knew it existed until the surprising archaeological unearthing of a dark soil stain led to a much fuller understanding of the cooperative role between the English and the state’s Native American community to withstand the wreckage of King Philip’s War.

Read more stories about Native Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Israel Putnam’s Revolutionary War Camps in Redding

During the harsh winter of 1778-1779, Israel Putnam, commanding general of the Connecticut militia, organized Continental Army encampments in the Redding, Connecticut area as part of George Washington’s encirclement of the British in New York City, and to support West Point. Three camp locations were set up, with the main camp along rocky slopes and a mountain stream in what is today’s Putnam Memorial State Park. The troops settled into winter quarters, where they endured many physical hardships, including frigid temperatures and a lack of food supplies. The snow was so deep that winter and mud so thick that spring that flour and bread stored in Danbury could not reach the camps. Joseph Plumb Martin, who endured winter camps at Redding and Valley Forge the previous year, wrote in his 1830 narrative “Private Yankee Doodle” that he suffered more in the winter conditions at Redding than he had with Washington at Valley Forge.

top right: students from Western Connecticut State University excavate the remains of an enlisted men’s hut in the northern end of the site at which Col. Moses Hazen’s men camped during the winter of 1778-1779. The rocks in the center of the photograph are the remnants of the collapsed chimney. Second from the left is Diana Messer who served as the site director for the 2008 season; bottom: A Revolutionary War re-enactor watches as a field crew from Western Connecticut State University excavates the remains of an enlisted men’s hut in the area where Col. Moses Hazen’s regiment spent the winter of 1778-79. photo: Samantha Mauro

Archaeological excavations have been conducted at the encampments over a span of many years beginning in the 1970s and have continued with the present research of Daniel Cruson, president of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut. One of the most dramatic archaeological discoveries was encountered during the initial excavations when David Poirier, retired SHPO staff archaeologist, found the butchered remains of horse in one of the fire-backs. It is one thing to read about the hardships and sufferings at Putnam’s camps, but quite another to handle the physical evidence. There are no historic descriptions of the Redding soldiers’ having resorted to eating their horses to survive. Archaeologically recovered horse bones provide that information, giving us a new and vivid perspective of their ordeal and their sacrifice for our budding country.

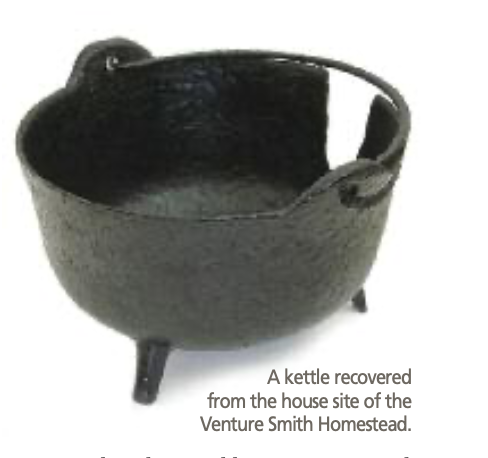

Broteer Venture Smith Homestead Site

Although the young Broteer Furro was born during the early 18th century into a royal family in Western Africa, he spent 30 years of his life as a captive in New England. Captured during a conflict between warring factions in his native land, Broteer would be sold into the slave trade, endure the horrifying Middle Passage, and serve a series of slave owners. Through his hard labor and entrepreneurship, he saved up enough money to purchase his freedom and eventually that of this wife, daughter, and sons. He would take the surname of the slave owner from whom he bought his freedom, and thus became known through the Long Island Sound area as Venture Smith. (See “Life & Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa,” Winter 2012/2013.)

As a free man, he supported himself and his family along the shore of Salmon Cove in East Haddam by farming, harvesting wood, trading up and down the river, fishing, and quarrying. Rising from captivity, Broteer Venture Smith would become landed, and though illiterate, accumulate wealth and live successfully within an Anglo-dominated world. In 1798, Broteer recounted his life story to a local teacher, who published it as The Narrative, which stands as one of the few written slave accounts that discusses life both in Africa and in captivity in New England. It is an extraordinary document that speaks of moral strength.

As a free man, he supported himself and his family along the shore of Salmon Cove in East Haddam by farming, harvesting wood, trading up and down the river, fishing, and quarrying. Rising from captivity, Broteer Venture Smith would become landed, and though illiterate, accumulate wealth and live successfully within an Anglo-dominated world. In 1798, Broteer recounted his life story to a local teacher, who published it as The Narrative, which stands as one of the few written slave accounts that discusses life both in Africa and in captivity in New England. It is an extraordinary document that speaks of moral strength.

As part of a multi-year archaeological study of the Connecticut Yankee property, a team of archaeologists led by Lucianne Lavin excavated the remnants of the Venture Smith Homestead Site. The “Homestead” consists of a cluster of nine stone-foundation ruins, landscaped hillsides for dry-docking, and fertile farm fields, situated near a potable spring and with access to the Connecticut River. The complex at one time had a main (center-chimney) house, two other residential structures, a blacksmith shop, warehouses, and wharf. Though the superstructures are long gone, the foundations and artifacts have been relatively untouched through the centuries, maintaining great archaeological integrity capable of yielding significant information.

Archaeological evidence consists of architectural and household artifacts and food remains, which have provided important and previously unavailable insights into the Smith family and their labors. Archaeology confirmed the vague references to farming and boating mentioned in the Narrative and yielded thousands of artifacts of everyday life, making available to historians a composite picture of one of the most significant lives and families in Connecticut’s past.

The legacy of Broteer Venture Smith is international in scope. His experiences represent the untold millions of Africans transported in the Middle Passage and destined for lives in captivity. Rising from the depths of slavery through hard work and determination, he achieved freedom and created a better life for himself and his family. Illiteracy did not prevent him from securing wealth from land and commodities transactions. His story challenges our concepts of human rights.

Archaeology and history are as much a part of our everyday lives as they are about the past. Ours is important work, and our collective responsibilities are to effectively transmit what we learn to public and future generations. So, when someone asks you where archaeological sites are located in Connecticut, just tell them—“Right down the street, and right beneath your feet!”

Read more about Venture Smith.

Nicholas Bellantoni is the state archaeologist.

Explore!

More stories about archaeology in Connecticut:

“Finding Isabel” Spring 2018

“Waste Not, Want Not: What a Colonial Midden Can Tell Us” by Ross Harper, Fall 2012

“Exploring and Uncovering the Pequot War,”

“Sites Underwater Worth Preserving, Too,” Spring 2009

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 54 Part I: The Long Journeys Home–Henry ‘Opukaha’ia

35 Minutes; Part II: The Long Journeys Home–Albert Afraid-of-Hawk

38 Minutes. Release Date: August 1, 2018

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 41: Have Archaeologists Found Connecticut’s Jamestown?

55 Minutes. Release Date: November 23, 2017

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 13: Discovery: Connecticut’s Most Important Dig Ever

42 Minutes. Release Date: August 23, 2016

See related photos HERE

.