(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

After a summer of training at Camp Yale on the grounds around the Yale Bowl on the western edge of New Haven, almost 4,000 doughboys prepared to leave for the European War. The men from across Connecticut who trained in New Haven in the summer of 1917 found camp life more than satisfactory, according to their letters and diaries. Camp kitchens served hot meals, and in between the drills, marches, and trench digging, young men smoked cigarettes and hung around together telling jokes.

The Girls Patriotic League, with a membership of thousands of young women from New Haven, erected two tents at Yale field that summer and several evenings a week hosted “dances for the soldier boys,” as local newspaper accounts held in the files of the New Haven Free Public Library described them. In his diary, Philip H. English, a motorcycle dispatch rider with the 26th “Yankee” Division, 102nd Regiment, and a member of one of New Haven’s oldest and wealthiest families, wrote, “Camp Yale was the best home the 102nd ever had.” Even a non-human would have agreed with this statement—because here at Camp Yale, a stout brown-and-white dog named Stubby appeared, who some say was lured off the rough streets of New Haven to a welcoming center of activity, friendship, and food. [See story, page 26.]

Members of the 102nd Regiment relax while cleaning their pistols, Camp Yale, summer 1917. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

The soldiers would soon set off for places they had never heard of, let alone ever visited, French and Belgian towns where millions had already lost their lives. But first, on August 27, 1917, the City of New Haven put on a special event for them in the Yale Bowl. One unidentified newspaper called it the “most unique night event, probably, that has ever been seen out of doors in New Haven or this state.” Fifty thousand Connecticut residents and departing soldiers and sailors were treated to a seven-act vaudeville and musical performance “where a perfect fairyland of electricity” created “one of the most remarkable and indescribable pictures possible,” the reporter remarked. After the circus-like acts and the playing of the Star Spangled Banner by the 102nd Regiment Band, the soldiers and sailors stood up and marched “across green grass that carpets the bowl, out into the street that led to their station.” According to the newspaper, “the cheers of farewell that greeted them nearly drowned out the playing of the great band.” The event was planned in exactly one week, since the 102nd Regiment had only been officially merged from two Connecticut National Guard units on August 20. The First Regiment (Hartford) and the Second Regiment (New Haven) had both existed since the early 18th century. But upon the U.S.’s joining the war, Connecticut, like all states, had to reach a quota of enlisted men based on population size. By combining the First and the Second C.N.G. into the 102nd Regiment—almost 4,000 doughboys, Connecticut nearly met its quota (though small contingents of National Guard members from Vermont and Massachusetts were added to fill out the ranks.)

The event was planned in exactly one week, since the 102nd Regiment had only been officially merged from two Connecticut National Guard units on August 20. The First Regiment (Hartford) and the Second Regiment (New Haven) had both existed since the early 18th century. But upon the U.S.’s joining the war, Connecticut, like all states, had to reach a quota of enlisted men based on population size. By combining the First and the Second C.N.G. into the 102nd Regiment—almost 4,000 doughboys, Connecticut nearly met its quota (though small contingents of National Guard members from Vermont and Massachusetts were added to fill out the ranks.)

Troops who had served in the Pancho Villa expedition on the Mexican border in 1916 [See story, page 20.] and others new to military life came to train together at Camp Yale. They soon took on an important new identity: that of the newly formed 26th “Yankee” Division of the American Expeditionary Force, under which the 102nd was placed. This new identity would be strengthened less than a year later when Companies C and D fought at Seicheprey in the Toul Sector of northern France. On April 20, 1918, 17 men from New Haven—among 81 from the regiment—died together—more than any other wartime event of the 20th century. Seicheprey became the touchstone for parades and memorial events in the Elm City from 1919 through the 1980s, when the last New Haven doughboys died.

Joining the War Effort

John Dillon (far left) and Fred Confrancesco (to his right), both of New Haven. Dillon was a member of Company C, 102nd Regiment, and survived the battle of Seicheprey. Courtesy of John T. Dillon, Esq.

Many New Haveners joined the war effort through support organizations, including the Y.M.C.A., the Red Cross, and the Knights of Columbus. Doctors from Yale University and the city’s hospitals became surgeons and medics on the front, men and women became ambulance drivers, and women joined as nurses or worked the many huts located in camps on the home front and on the western front and managed by the Knights of Columbus. The city’s pastoral staff from First Church on the Green (Center Church) and Plymouth Congregational Church boosted recruitment by holding “Second Regiment Sundays” in their churches, but they went to France, too. Dr. Oscar Maurer of Center Church went to the front as a volunteer for the Red Cross to attend burials for American soldiers, while Rev. Orville A. Petty of Plymouth Congregational Church—called the “Fighting Parson”—went to the front as the regimental chaplain for the 102nd.

Recruiting got underway in earnest well before the draft began in spring 1917. Men were encouraged to enlist where their skills could be put to use—and shamed into enlisting ahead of the draft. In New Haven on June 6, 1917, the Rev. Harris E. Starr, pastor of Pilgrim Congregational Church and chaplain of the Home Guard, spoke to 200 people in New Haven’s Wooster Square, saying,

Now is the opportunity for men with aspirations to enlist in the Second Regiment. While it will be no disgrace to be drafted, the men who are will be cheating themselves of an opportunity to get in out of the draft by joining the Second Regiment. The men who are drafted won’t be congratulated on the street by friends; to the contrary they will be considered somewhat shaky and uncertain.

If you were a white man between the ages of 18 and 40 and enlisted before the draft called your number, you could choose from a long list of jobs needed to support the war effort. The State of Connecticut and city leaders promoted these options at “regiment recruiting parties” to raise enlistee numbers before the draft began.

Connecticut newspapers reported that 163 men were needed to work as stenographers, storekeepers, cooks, brakemen, engineers, firemen, yard foremen, electricians, linemen, gasoline engineers, draftsmen, surveyors, car inspectors, pile drivers, pipefitters, boiler inspectors, boiler makers, water-supply men, and blacksmiths. Of the 163 spots, all but 43 filled quickly, with blacksmiths being in highest demand. Men who wanted to join the United States military in this fashion were examined by Major William P. Wooten in New Haven and then sworn in.

Some men enlisted with “railroad regiments,” small regiments of skilled workers already working for railroad companies. Railroad regiments went to France to build railroads and run trains for the allies and the upcoming influx of American soldiers. One of these regiments was assigned to New England, from which 10 companies—two of them based in New Haven—were formed.

But it was really the draft that brought in the needed numbers: more than 20,000 New Haven men registered for selective service, with 8,000 claiming exemption due to health or hardship. Only one—Rudolph C. Dahlberg, whose name and address were printed in the city’s newspapers—asked to be exempt from service as a conscientious objector.

While some New Haven men became members of the 102nd Regiment, others enlisted in other army divisions or became pilots with the fledgling aviation section of the Army Signal Corps or seamen with the United States Navy. A few joined the British and Canadian expeditionary forces, likely due to family connections. Foreign units toured the United States on their own recruiting missions; it didn’t become illegal to join a foreign army until World War II. The Fifth Royal Highlanders recruited throughout New England in October 1917; the “Black Watch Tour” gained 1,000 men, according to one newspaper, including Jonathan Boswell and Donald Bothwell, both New Haveners, who served and died with the Black Watch division of the British Army.

While some New Haven men became members of the 102nd Regiment, others enlisted in other army divisions or became pilots with the fledgling aviation section of the Army Signal Corps or seamen with the United States Navy. A few joined the British and Canadian expeditionary forces, likely due to family connections. Foreign units toured the United States on their own recruiting missions; it didn’t become illegal to join a foreign army until World War II. The Fifth Royal Highlanders recruited throughout New England in October 1917; the “Black Watch Tour” gained 1,000 men, according to one newspaper, including Jonathan Boswell and Donald Bothwell, both New Haveners, who served and died with the Black Watch division of the British Army.

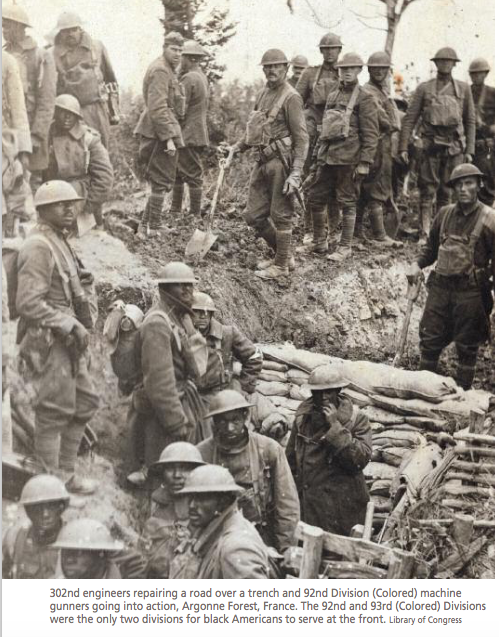

The choices for African American men were much narrower. Thousands of black men joined the United States Army, but few ended up fighting at the front. Many were looking for a way to serve their country and for the prospect of greater economic and social opportunity when the war was over. But black men were underutilized and marginalized by the U.S. military, which assigned them to work as laborers, stevedores, and grave-diggers. The French Army, by contrast, guided by more liberal cultural attitudes and the need to reinforce their steeply depleted ranks, took two divisions of black men into their army.

New Haven’s 1st Lt. Charles Henry Barclay—a sign-painter who lived on Ashmun Street, was one of these soldiers. His Connecticut National Guard regiment (as part of the First Separate Company of the C.N.G.’s Second Regiment) became part of the 372nd Regiment of the 93rd Infantry (Colored Division), serving under the French 157th or “Red Hand” Division.

Serving on the Front

In the first few days of September 1917, the New Haven Register reported on a few of the first men to leave New Haven for Europe. John Dillon of 56 Bright Street in Fair Haven, a soldier with the 102nd Regiment, was from the Irish-American section of New Haven. Dillon—born in Ireland, and still a citizen of that country when he enlisted—was like many thousands of young men who joined the U.S. Army in 1917. Many, like him, were immigrants and first-generation Americans, were not college educated and worked in offices, factories, and shops.

Another member of the 102nd Regiment, also with Company C, was Edward Schafer [See story, page 14.], a tally clerk at Winchester Repeating Arms Company and the son of German immigrants, whose handwritten memoir (a copy of which is held in the Connecticut State Library) observed,

My folks … loved this country [and]were surprised at the freedom of opportunity that wasn’t available in the old country. They … hoped the American people wouldn’t be lolled into complacency and let the freedoms be lost.

Schafer’s memoir and Dillon’s World War I diary, a pocket-sized daily calendar, demonstrate the humility with which both undertook their service. Schafer wrote simply that their role was “to know one’s place and duty.” A small incident noted by Dillon on September 25, 1917 while he was en route to Europe is both mundane and touching. A fight he got into with the cook (“sorry I hit him”) ended quickly; the next day Dillon wrote “cook and myself good friends again.”

The 102nd Regiment landed in Southampton, England in October 10, 1917. Dillon described it as “one Hell of a hole” but was more introspective upon leaving, writing “glad to get out of here…don’t know what we will hit in France.” When the 102nd finally landed in Havre, France on October 17, 1917 at 1 a.m., Dillon noted that his regiment had to march 10 miles in the rain before a brief rest, followed by another 8 miles that evening to reach a railroad station at 9 p.m. “Rest camps be darned,” he wrote.

By early November, after a few weeks of training by the French in trench warfare, Dillon reported that the 102nd was inspected by General Pershing, General Edwards, and staff. They didn’t do well, according to Dillon: “the skipper got ‘Hell,’ the Lieut. got ‘Hell’ and we got ‘Hell’…another Inspection at Retreat and we’ll get ‘Hell’ again…5:30 p.m. [we did].” A few days later, the 102nd wore steel helmets (replacing the soft, less protective “campaign hats” they’d grown accustomed to wearing during the summer) for the first time. Schafer said there were no complaints, but the helmets “didn’t protect the back of your neck.” They continued to dig trenches as the weather turned from rain to snow.

At the end of November the doughboys celebrated Thanksgiving with a turkey dinner and pie. The cold days of December and January were taken up with drills to familiarize soldiers with new equipment, including bayonets, automatic rifles, and gas masks. Dillon marked his 22nd birthday on December 17, but nothing else special is mentioned until his Christmas-day entry, in which he reports having taken Holy Communion at 6:30 a.m. and then went on bucket brigade to fight a fire in the guard house. Schafer’s memories of his first Christmas at the front were about the presents from home. “Our bunks were so covered by gifts we slept on the floor…”

On December 28, 1917, in the middle of a snowstorm, the 102nd took over the trenches from the 101st Regiment and began its 11 months of active service on the front. By the next day, Dillon had a frozen toe that bothered him for weeks, a particular problem for a dispatch runner. In the coming months, a sore toe would come to mean little.

The 102nd Regiment fought at the Chemin des Dames, Toul Sector/Seicheprey, Aisne-Marne, Chateau-Thierry, St. Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne, all of the major battles in which Americans participated. Dillon, Schafer and the 102nd Regiment were exposed to the full horrors of war: gas attacks, hand-to-hand combat with bayonets, artillery barrage, shrapnel wounds, disease, the death of friends, and, as Capt. Daniel Strickland noted in Connecticut Fights: The Story of the 102nd Regiment (Quinnipiack Press, Inc., 1930) multiple times, the “ever present damnable mud all about.” No one at the front could write his memoirs without mentioning the mud, but there were also the rats, which were described by Dillon as being “as big as dogs.”

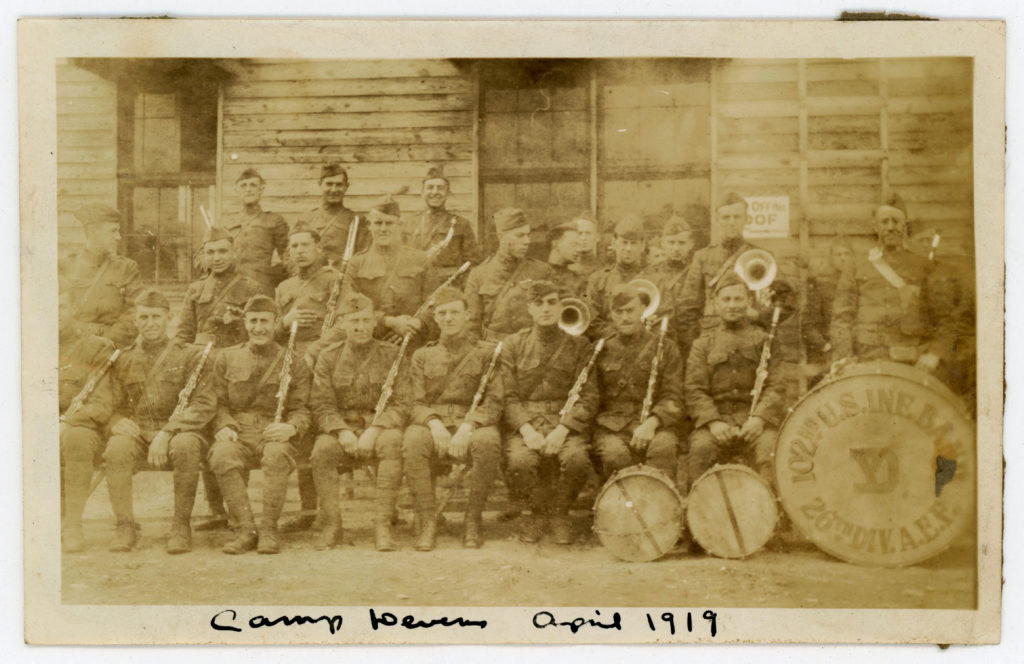

The 201nd Regiment Band, 26th Division, Camp Devens (Massachusetts), April 1919, after the division mustered out. Courtesy of Robert S. Greenberg, Made in New Haven Collection

About the war’s end, Schafer wrote, it was “impossible to portray that feeling when the orders were passed down from man to man in the trenches.” On that 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, the Elm City had lost more than 261 men and two women, including Irene M. Flynn and Helen A. Moakley, both nurses with the American Red Cross who died of the Spanish flu. Of the 250 soldiers of Company C, 102nd Regiment, 26th Division, only 43 survived, John Dillon and Edward Schafer among them.

Camp Yale and that Monday evening under the stars at the Yale Bowl, when flickering lights and music filled the stadium and the city and state cheered for the departing soldiers and sailors, was both 15 months and a lifetime ago. Daniel Strickland, a member of Company D who was wounded in action, remembered Camp Yale this way,

John Dillon leading the New Haven Chapter of the Yankee Division, likely during its annual Seicheprey Observation Day event in April, late 1930s. Courtesy of John T. Dillon, Esq.

Company by company, or by battalions, the regiment through September and October folded up its tents and stole away between the shadows of twilight and the mists of morning, leaving finally a bare stretch of ground where had once been Camp Yale. In days to come when reports from France were meager, and while the casualties grew, fathers and mothers, wives and sisters, brothers and friends were to pilgrimage again and again over that rutted and bare area and seem to hear once more the shouting of orders and rattle of mess kits, and to conjure up the ghosts of those boys that had become grown-ups in a short summer, and were now transplanted to stand like strong young oaks between other homes and the withering blast of fire on the Western Front.

The author thanks Robert S. Greenberg, Made in New Haven; John T. Dillon, Esq., the son of John T. Dillon, who generously made his father’s materials available; and Christine Pittsley and the staff of the Connecticut State Library.

Laura A. Macaluso is the author of New Haven in World War I (The History Press, 2017), endorsed by the World War One Centennial Commission (worldwar1centennial.org/). She wrote “New Haven’s Monuments Man,” Winter 2014/2015.