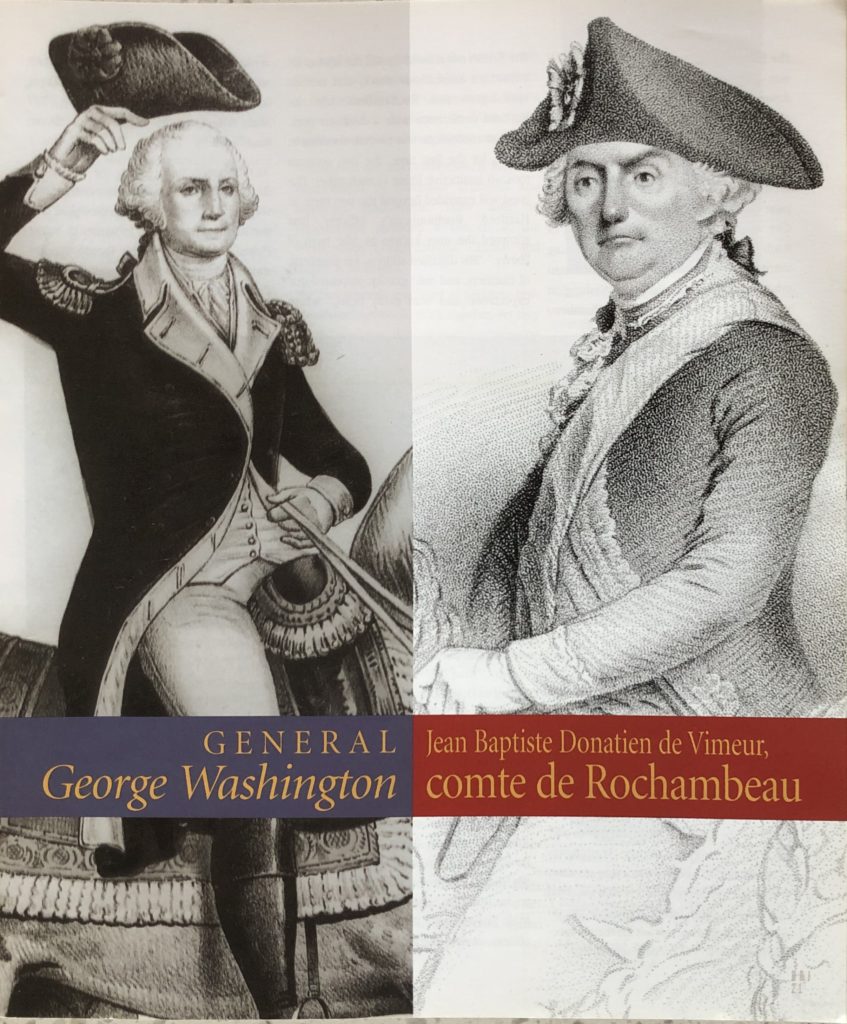

left: Washington by E. B. and E. C. Kellogg; right: comte de Rochambeau, D. C. Hinman after John Trumbull, c. 1800. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

By Ann Harrison and Mary Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

France’s decision to assist the struggling Continental Army was predicated on the belief that helping the Americans win their independence was a way to cripple Great Britain. But the French army would have to cross Connecticut to achieve that goal. For its role as a central location for plotting how and where the French and Americans would confront the British, the Constitution State could well have been called “The Conference State.”

Though no major battles were fought here, Connecticut played a central role in the French/American alliance, both literally and figuratively. Located between Newport and the Continental headquarters in what is now White Plains, New York, Connecticut would prove to be a convenient place to stop on journeys to or from Newport to Phillipsburg (then on to Yorktown, Virginia) and, later, from Yorktown to Boston.

General George Washington met his French counterpart, comte de Rochambeau, for the first time at the Hartford home of Jeremiah Wadsworth. Less than a year later, at Joseph Webb’s house in Wethersfield, Washington made his case for a joint offensive on the British forces holding New York City. Lebanon would host a French cavalry unit during a long winter as Washington and Rochambeau debated strategy. Other Connecticut residents active in the quest for independence included Lebanon ‘s William Williams, who signed the Declaration of Independence, and Governor Jonathan Trumbull, known to Washington as “Brother John.”

The battle that ended the Revolutionary War ultimately was won not in New York but in Yorktown, Virginia, on October 19, 1781. But those early conferences in Connecticut brought together two pillars of the military world: it was here that they met face to face and planted the seeds of lifelong, mutual admiration.

The Hartford Conference

General Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, was chosen by the French to lead the army that would join Washington’s forces. He’d previously been tapped to lead an invasion of England. That mission was aborted, and he was put in charge of the Expedition Particuliere, the code name for the French legions sent to help the Americans.

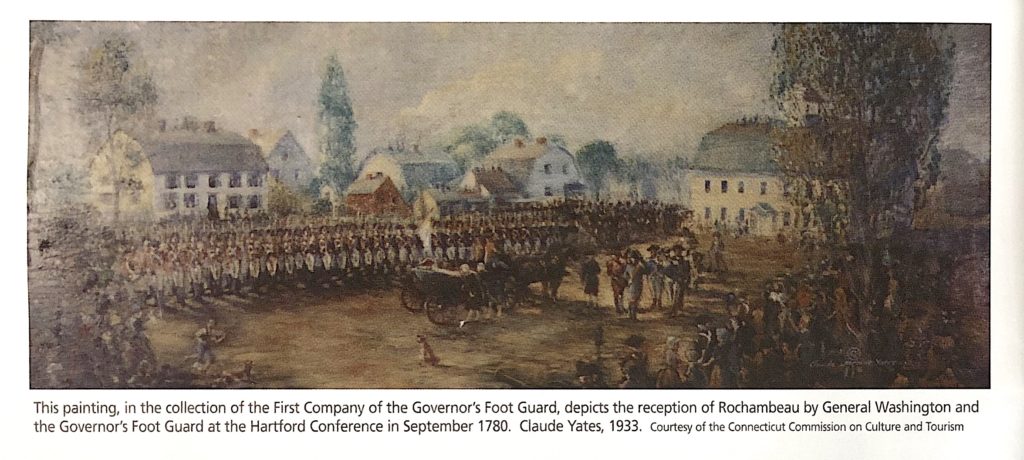

Rochambeau received by General Washington and the Governor’s Foot Guard, September 1780. By Claude Yates, 1933.

Rochambeau arrived in Newport in July 1780 with close to 6,000 men. The French general refused to proceed south to engage the British without more troops, the French naval fleet, or a clear plan of attack. He did agree, though, to start meeting with Washington in the meantime.

Washington officially greeted his ally in front of what is today the Old State House on September 20, 1780. Hartford ‘s 5,000 inhabitants turned out in force to greet the French delegation. A 13-gun salute from the Governor’s Guard rang out as the French disembarked at the ferry landing after crossing the Connecticut River. The two leaders and their entourages then walked a few blocks south to the home of Jeremiah Wadsworth for a reception. Wadsworth’s home, where the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art now stands at 600 Main Street, was also their conference site.

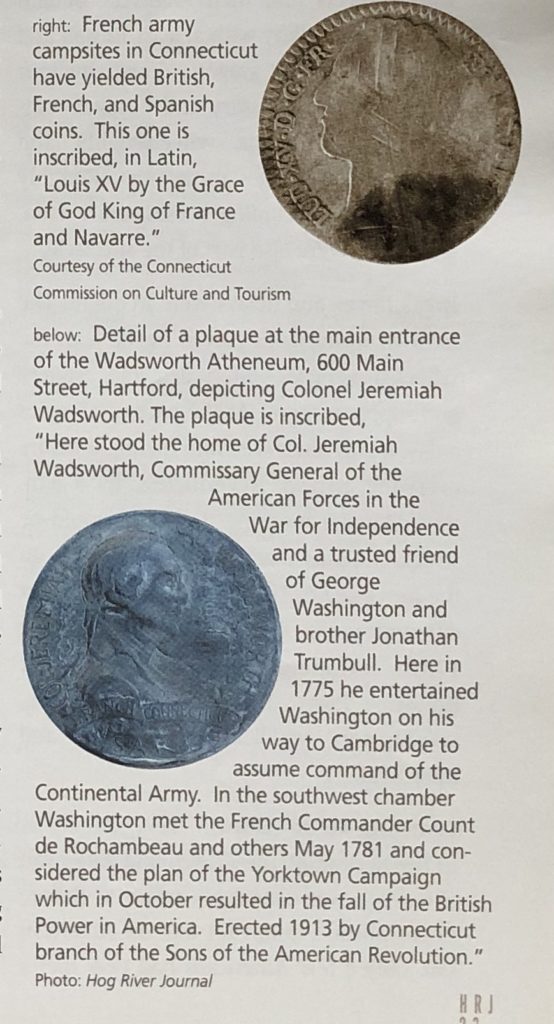

Wadsworth was an activist for American independence, serving as a commissary for the Continental and French armies and later working to secure ratification for the U.S. Constitution in Connecticut. Buying in bulk for the army was not an easy task for someone representing the fledgling U.S. government; he was forced to use that government’s devalued currency to supply a joint military venture with a country that had just recently been our enemy (in the French and Indian War, 1756-1763). Wadsworth used a mixture of threats and flattery to persuade Connecticut suppliers to trade. Backed by French coin, he ultimately prevailed by appealing to the American sense of duty-and the profit to be made. His efforts inspired a later Connecticut nickname, “The Provision State.”

“Never let it be told that Twenty Ton of hay could not be found for hard money,” wrote Wadsworth. “Our Enemies will believe we are not in earnest to oppose them; our Friends will have reason to complain.”

The Hartford conference, in September 1780 was prompted largely by Rochambeau’s desire to cut to the chase and avoid a flurry of letters between him and Washington arguing the pros and cons of taking on the British at New York City.

Washington brought to Hartford an eight-page outline for an operation in New York City, hoping to stage it before the onset of winter. (His plan was backed by a young marquis de Lafayette, a French nobleman who had been in the service of Washington since early in the revolution.) Rochambeau and his second in command, chevalier de Ternay, wrote out their thoughts and ideas in column form, which Lafayette translated for the Americans. Lafayette wrote Washington’s answers, translated into French, in a parallel column for Rochambeau and Ternay to read. This summary of arguments was later published by the United States Congress as part of “The Writings of George Washington (1745-1799).” The conference was cut short when, late on September 21, news arrived that British naval forces were massing off New York. Both generals left for their respective headquarters to prepare separately.

The British naval build-up did not lead to an immediate amphibious attack, and neither Washington nor Rochambeau left the Hartford conference with a finalized plan. Yet that conference was pivotal: meeting in person for the first time, the two generals took an instinctive liking to each other. The goodwill extended beyond the two men: in Hartford, Rochambeau’s officers first glimpsed the man known as “the hero of liberty.” “His dignified address, his simplicity of manners, and mild gravity, surpassed our expectation and won every heart,” wrote Mathieu Dumas, a French officer, upon meeting Washington.

Washington made four visits to Hartford during his life. Each time he was entertained at Wadsworth ‘s home. (Two plaques at the Wadsworth Atheneum commemorate these summits.) Dumas and other French and American officers likely were lodged at David Bull’s Tavern, marked by “The Sign of the Bunch of Grapes,” strategically located across from the State House at 800 Main Street. Bull’s Tavern was also used by officers during the French army’s march across Connecticut in June 1781 and their return march in the fall of 1782. A plaque in the Bank of America building, 777 Main Street , marks where Bull’s Tavern once stood.

As the strategy for defeating the British was finalized during 1780-81, the French army went into winter quarters in Newport, and the Americans prepared to winter in White Plains. But not all of the French support stayed in Newport. The cavalry came to Connecticut .

A combined cavalry/light infantry unit led by Armand Louis de Gontaut, duc de Lauzun, headed to Lebanon, the home of Governor Jonathan Trumbull and William Williams. “Lauzun’s Legion” included about 250 hussars, or cavalry, and an infantry component of grenadiers, chasseurs, and cannoniers. With forage for horses in short supply in Newport, the green hills of Connecticut were the perfect place to await orders.

The Wethersfield Conference

The planned winter encampment in Lebanon ended up lasting almost eight months, from November 1780 to June 1781. During that time, a second key conference took place in Connecticut, when Rochambeau and Washington met again from May 21 through 23, 1781 in Wethersfield, the home town of Silas Deane.

Deane had represented Connecticut in the first Continental Congress in 1774. Two years later, prior to the Declaration of Independence, Deane was dispatched to France by a secret committee of the Continental Congress.

Deane’s business in France was cloaked in secrecy. As Congress’s commercial agent and covert representative, he was charged with buying clothes, arms, and ammunition and negotiating treaties of alliance and commerce with the French. Not wanting to alert the British to the extent of French support for the American cause, Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (author of The Barber of Seville ) assisted Deane by establishing a phony trading company that channeled supplies and funding to the Americans. Spain and Portugal were also silent allies, supplying goods and coins.

Deane was joined in France by Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia and Arthur Lee of Virginia. In 1778, less than two years after Deane arrived in France, the French entered into a Treaty of Alliance with the colonies in 1778, signed by Deane, Franklin, and Lee.

Back in Wethersfield, the Joseph Webb House on Main Street was offered to Washington as lodging and meeting space. Deane’s house, right next door, was used by Washington’s staff, since Deane was still in France. Down the street, Nathaniel Stillman’s Tavern served as the French staff quarters.

Joseph Webb’s and Silas Deane’s houses are now part of the Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum at 211 Main Street in Old Wethersfield. Together with the Isaac Stevens House, which was built in 1789, the museum is the centerpiece of Connecticut ‘s largest historic district. A plaque on Main Street marks where the Stillman Tavern stood.

Washington and Rochambeau were joined in Wethersfield by Governor Trumbull and Jeremiah Wadsworth. Their time in Wethersfield included a concert at the Wethersfield Congregational Church and dinner at Stillman’s.

The two generals continued to negotiate how the two armies would work together, yet they still did not know their ultimate confrontation with the British would be at Yorktown. Throughout the conference, Washington continued to push for an offensive to recapture New York City. After the French broke camp in Newport and Lebanon and moved to eastern New York to join Washington, the French naval fleet entered the Chesapeake Bay. French and American forces were directed on August 20, 1781 toward Yorktown, where Britain’s Lord Cornwallis would surrender on October 19, 1781.

Crossing Connecticut

Rochambeau landed in Newport with close to 6,000, but that number dropped to about 4,700 plus officers due to sickness and death after the long journey from France. Following a central path through Connecticut, they covered 120 miles between June 19 and July 2, 1781. The hussars in Lebanon broke camp on June 21 and followed Rochambeau’s route, while small detachments roamed over wide areas on the lookout for British or loyalist forces.

Except for episodes in Danbury, Fairfield, and New London, Connecticut was spared major military conflict during the Revolutionary War. But the columns of marching men, artillery, and supply wagons that stretched for miles along the narrow and stony roads during the summer of 1781 were a very real manifestation of the conflict raging elsewhere and an interruption of 18th-century Connecticu ‘s quiet, agrarian landscape.

Except for episodes in Danbury, Fairfield, and New London, Connecticut was spared major military conflict during the Revolutionary War. But the columns of marching men, artillery, and supply wagons that stretched for miles along the narrow and stony roads during the summer of 1781 were a very real manifestation of the conflict raging elsewhere and an interruption of 18th-century Connecticu ‘s quiet, agrarian landscape.

For each of the four French regiments, engineers carrying axes and shovels came first to clear and repair roads and bridges along the route that would eventually cover close to 700 miles. An entire infantry of almost 1,000 officers and men followed. Behind them came artillery with at least 12 staff and regimental supply wagons drawn by four oxen each. Commissary and hospital wagons, forage wagons, wheelwrights, and mobile camp forages came next. Roughly seven hundred animals, including horses, draft oxen, and cattle, were also part of the spectacle.

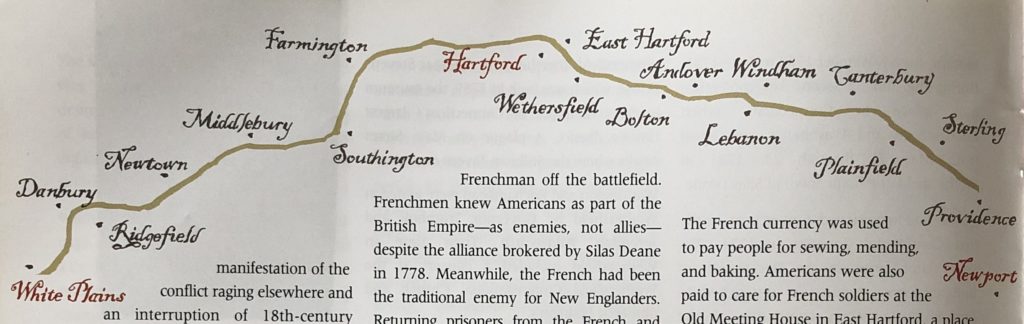

Breakdowns and delays were frequent. The narrow, rocky roads played havoc with the wheeled vehicles, often delaying artillery and supply wagons. At the pace of 15 miles a day, it was often well into the night before everyone arrived. Nevertheless, by 5 a.m. the following morning the tents would be struck, wagons loaded, and the troops on the move again. This occurred nine times at different camps across Connecticut during 1781, including Plainfield, Windham, Bolton, East Hartford, Farmington, Southington, Middlebury, Newtown, and Ridgefield.

Learning To Be Allies

In the beginning, the French and American alliance was under strain. Before Rochambeau’s troops set foot on American soil, only a few Americans had ever met a Frenchman off the battlefield. Frenchmen knew Americans as part of the British Empire–as enemies, not allies–despite the alliance brokered by Silas Deane in 1778. Meanwhile, the French had been the traditional enemy for New Englanders. Returning prisoners from the French and Indian War relayed their experiences in accounts that were invariably anti-French.

Trade helped make the alliance work. Purchases made by Jeremiah Wadsworth as commissary for the French army were a boon to the state’s economy because he could pay with real French silver, as opposed to the near-worthless paper money printed by Congress since 1775. Food, materials, and gunpowder were transported from outlying areas to a depot in Danbury and then distributed. Trade in the camps along the route flourished and fostered good will on a personal level between the regularly paid French soldiers and the Americans.

Rochambeau’s coffers had to be refilled 11 times during his time in America. Fast frigates and high-seas convoys were the only ways to get money safely to these shores without their being intercepted by the British. On land, wagons carried barrels of coins over the rough Connecticut terrain.

East Hartford’s Silver Lane probably got its name because the French quartermaster doled out pay from a house there, close to the camp used from June 24 through 26, 1781, and on the return march October 29 to November 4, 1782. The Timothy Forbes house on Forbes Street briefly stored barrels of coin. When the army moved, Forbes drove the coin in a cart to New York at a rate of $2 a day. Timothy Forbes’s house still stands at 135 Forbes Street.

The French currency was used to pay people for sewing, mending, and baking. Americans were also paid to care for French soldiers at the Old Meeting House in East Hartford, a place of worship at the intersection of Main Street and Pitkin Street that served as a French hospital. A plaque where Main Street and Pitkin Street merge commemorates the meeting house site. Not far away, Rochambeau lodged at Squire Elisha Pitkin’s house (relocated from Pitkin Street to Guilford, Connecticut in 1955). A plaque in Elizabeth Shea Park in East Hartford (201 Silver Lane ) commemorates camps made by soldiers marching to and from Yorktown.French soldiers’ personal journals make frequent references to pretty American young ladies encountered during the march and of the locals’ willingness to trade. A journal entry of French soldier George Daniel Flohr described his time in camp in Farmington June 25 through 29, 1781: “As soon as we had set up our camp there and the Turkish Music could be heard playing prettily, such a large number of inhabitants assembled there that one was surprised and had to wonder where all these people were coming from since we had encountered very few houses along our way during the daytime.”

The troops left Farmington and marched 13 miles to their next camp, near Asa Barnes’s Tavern in the Marion section of Southington, with Rochambeau taking quarters in the tavern over four days. Rochambeau’s generals and colonels decided to give a social ball in an open field near the camp site. The celebrations–infused with spirits provided by Asa Barnes’s Tavern–spanned the four nights they were in Southington. Rochambeau revisited Barnes’s Tavern again on the return march in October 1782.

The site of the Asa Barnes Tavern is now a private residence (1089 Marion Avenue, Southington). The original building was damaged by fire in 1836, but the extent of the damage is unknown. It was rebuilt in the then-popular Greek Revival style. The area it is located in is still known as French Hill, and a marker at 1038 Marion Avenue commemorates the French campsite.

Good relations with the French continued after the war. In 1782, when the French troops made 10 camps in Connecticut on their return march to Boston — and to ships bound for home — they were greeted with the gratitude of a united America.

A Mutual Appreciation

Much has been made of revisions to Revolutionary War history that shattered the belief that the battle of Yorktown was planned in Wethersfield. Both American and French correspondence illustrates that New York City remained Washington ‘s focus for months after the second Connecticut conference in Wethersfield in May 1781. The arrival of the French Navy in the Chesapeake Bay in late summer 1781 caused the Americans and French to look southward.But those days in Connecticut taught the two generals–as they huddled over maps and lists of arguments–how to work together. Rochambeau’s patience and methodical style were showcased, and Washington’s “mild and open countenance” helped win the hearts of French officers, even when strategies diverged.

Ann Harrison was the coordinator for the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route state project in Connecticut. Mary Donohue was the survey and grants director and architectural historian for the State Historic Preservation Office of the State of Connecticut. She is co-author of En Avant with our French Allies, a guidebook to Connecticut sites, markers, and monuments along the Washington-Rochambeau route.

Explore!

“Mapping Rochambeau’s March Across Connecticut,” Spring 2012

“Benedict Arnold and the Battle of Ridgefield,” Winter 2017-2019

“Fairfield Set Ablaze,” Spring 2009

“Benedict Arnold Turns and Burns New London,” Fall 2006

Read more stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page.