(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

Between June 27 and June 29, 1916 nearly 3,000 Connecticut National Guardsmen left Camp Holcomb in Niantic, bound for the Mexican border. The reasons for their journey are directly related to events stemming from the Mexican Revolution of 1910 and the almost constant state of flux in political and military affairs that followed and to the long history of instability and cross-border incursions that characterized the region in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

On March 9, 1916 the Mexican General Francisco “Pancho” Villa and several hundred of his troops attacked the small border town of Columbus, New Mexico, an action that left 18 American civilians and soldiers dead and a significant portion of the town in ruin. The soldiers were members of the U.S. 13th Cavalry, assigned to nearby Camp Furlong, one of many U.S. military installations that stretched from Brownsville, Texas to Nogales, Arizona. Construction of most of these outposts had begun in the 1850s, following the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, which added much of southwestern New Mexico and southern Arizona to the United States and created a border that needed to be patrolled and secured.

Villa had emerged as a popular leader from the political and military turmoil following the Mexican Revolution of 1910, which had deposed Porfirio Diaz, dictatorial ruler of Mexico since 1876. The wealthy class had prospered under Diaz’s encouragement of foreign investment and industrialization, while the lower classes and small farmers suffered as a result of his patronage of large landholders and ranchers. Diaz’s despotism and repression finally drew a concerted response, and he fled in exile to Paris in 1911. What followed was a decade’s worth of rival factions’ vying for power, with constantly shifting military alliances, pitched battles, and assassinations, and a growing, but unanswered, demand for broad social reform by the country’s dispossessed.

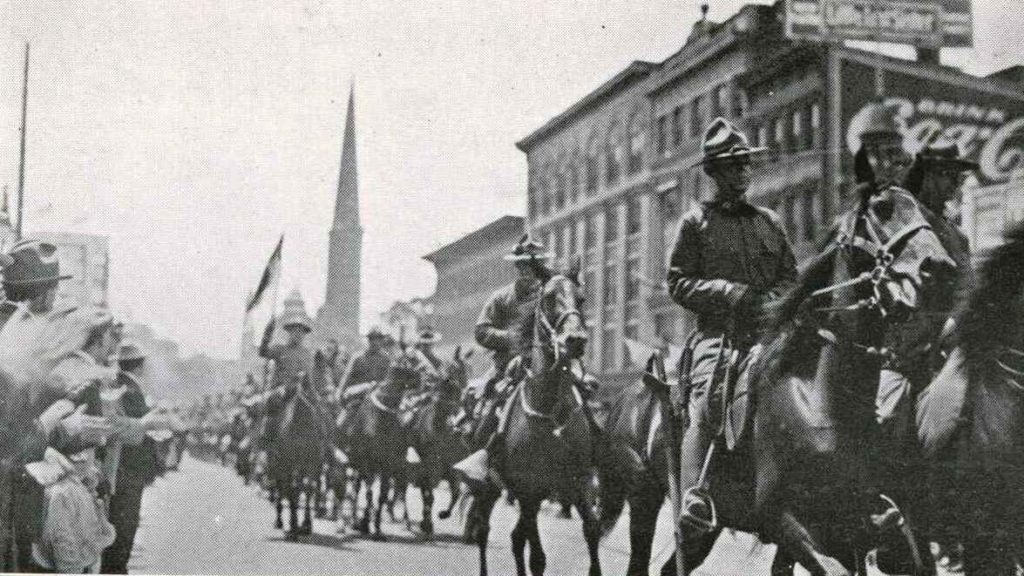

Troop B Cavalry parading on Main Street in Hartford on their way to Niantic, June 23, 1916. From Origin and Fortunes of Troop B

By August 1914, Venustiano Carranza emerged as the leader of the revolutionary Constitutional Party, recognized by President Woodrow Wilson as the de facto Mexican government. Gen. Villa was allied with Carranza and in command of troops in the state of Chihuahua and northern Mexico, but a growing dispute between Carranza and Villa eventually led to a decisive battle between their respective forces in November 1915. Villa was soundly defeated, but he remained a threat to Carranza, raiding towns in northern Mexico and attacking Carranza’s Federal Army. His attack on Columbus, New Mexico was an effort to embarrass Carranza and provoke a response from the United States.

President Wilson’s response was almost instantaneous. On March 10 Wilson ordered Brigadier General John J. Pershing to cross the border into Mexico and undertake a punitive expedition to pursue and apprehend Villa. By March 14 Pershing was leading four cavalry regiments, two infantry regiments, and part of a field artillery unit on a mission that eventually took them nearly 400 miles into Mexico. Unsuccessful in its objective of capturing Villa, who was at home in the mountains of northern Mexico and easily eluded Pershing, the U.S. forces were finally recalled in February 1917.

Calisthenics were part of the daily routine in camp at Niantic. State Archives, Connecticut State Library

Pershing’s expedition had angered Carranza and many Mexicans, who viewed it as a violation of the country’s sovereignty. Carranza had denied Pershing the use of Mexican railroads to move troops and supplies, resulting in the first large-scale use of motorized trucks in a military operation by the U.S. Army.

Most of the troops with Pershing had been stationed in forts along the border. But because those forts were undermanned, border towns were seen as vulnerable to attack by bandits or portions of Villa’s troops not being chased by Pershing. On June 19, 1916 President Wilson federalized the National Guard and ordered nearly 150,000 National Guard soldiers to report for duty protecting the border between the United States and Mexico. This was the first time such action had been taken, with Wilson empowered by recently enacted reforms of both the regular army and the National Guard. The guardsmen were to be deployed at strategic points along the border from Brownsville to Nogales usually in proximity to a regular army installation.

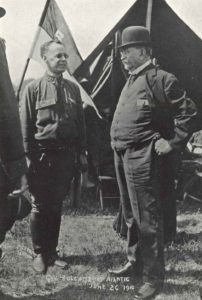

Gov. Marcus Holcomb (right) and Capt. John H. Davis of Troop B at Niantic, June 26, 1916. From Origin and Fortunes of Troop B

Upon receipt of Wilson’s order, Governor Marcus Holcomb ordered Connecticut National Guard units to report to Camp Holcomb in Niantic to await further orders from the U.S. government. Units ordered to Niantic were the 1st and 2nd Connecticut Infantry, Troops A and B Connecticut Cavalry, 1st Connecticut Field Company Signal Troops, 1st Connecticut Field Hospital Company, and 1st Connecticut Ambulance Company. Private Ernest F. Schmith of Meriden, a member of Company L, 2nd Connecticut Infantry, noted in his diary that he arrived in Niantic on June 24 around 7 p.m. “Got tents pitched about 10:30 then had mess. Nothing of importance happened at Niantic only regular camp routine and rain. Rookies got initiated.”

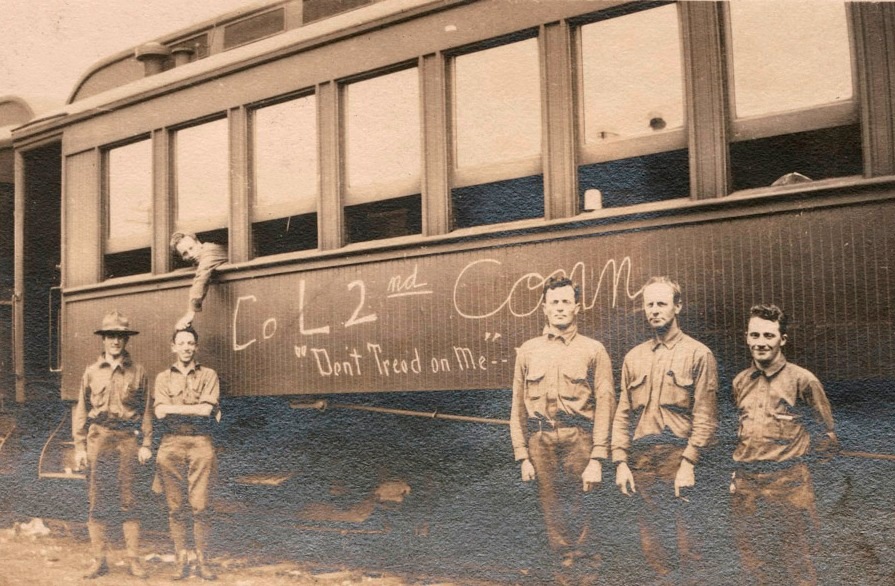

Schmith was one of the nearly 3,000 Connecticut National Guardsmen who left Niantic for Mexico between June 27 and June 29. The Hartford Courant reported that the troops left in eight trains, averaging 14 cars each. The trains consisted of coaches for the soldiers, flatbeds for ambulances and supply wagons needed in the field, and boxcars carrying supplies, horses for Cavalry Troops A and B, and horses to pull the ambulances and supply wagons. Officers were assigned to sleepers and enlisted men were put in day coaches—three men to two seats, making for an uncomfortable journey at best. In an attempt to lighten the mood, guardsmen adorned the sides of their coaches with slogans and pictures drawn in chalk. One coach was ornamented with “Co. L 2nd Conn. ‘Don’t Tread on Me’.” As Captain Daniel W. Strickland later reported in “The Mexican Border Mobilization,” in Connecticut Fights: The Story of the 102nd Regiment, “Some of these [slogans]were not very complimentary to the Mexicans, requiring the use of soap and water, much like the treatment mothers used to give little boys for using bad words.”

Men of Company L, 2nd Infantry Regiment and their chalk-decorated coach. Corp. Merritt E. Learned Collection, courtesy of Alan D. Learned

Since nearly the entire National Guard was on the move at the same time, with 150,000 troops funneling down toward the Mexican border from every part of the United States, every available piece of rolling stock was put on the rails by the nation’s railroads, and military trains were given priority over civilian traffic. All along the route, crowds lined the tracks as the trains passed by, cheering and shouting encouragement to the troops.

In his order federalizing the National Guard, Wilson stressed, “This call for militia is wholly unrelated to General Pershing’s expedition and contemplates no additional entry into Mexico, except as may be necessary to pursue bandits who attempt outrages on American soil.” The Connecticut troops knew that their destination was “somewhere on the border,” yet, as Major James L. Howard of Troop B Cavalry reported, “Youthful imaginations…recently had been kindled by a reading of Prescott’s glowing story of the Conquest of Mexico. To follow the path of Cortez; to storm the heights of Chapultepec after the manner of Tom Seymour in 1846; to look upon the lakes and palaces of Mexico, the most ancient city of America; to encamp among the temples of a vanished race—was ever a more fascinating prospect offered to a soldier of fortune?” (as noted in The Origin and Fortunes of Troop B, James L. Howard, editor, Case, Longwood and Brainard Co., Hartford, 1921).

Any romantic notions about their duty at the border were quickly dispelled when the Connecticut troops alighted in the border town of Nogales in the blazing July heat. Captain Strickland noted, “The rocky ground was so hot men stood about on the edges of the soles of their shoes. Almost all…of the men started in with a prolonged nose-bleed, while a mid-day sun beat down with a white-gray dust, the temperature being something over one hundred and twenty-five degrees.” It took several weeks to adjust to the climate, and eventually, the troops were exempted from any strenuous duties between the hours of 11 a.m. and 3 p.m.

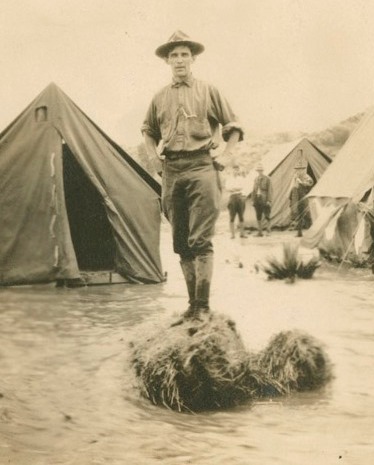

A Connecticut soldier stands on a hay bale in the midst of the flood camp at Nogales. Corp. Merrit E. Learned Collection, courtesy of Alan D. Learned

The first night in camp was spent in pup tents, and sentries were posted, since Mexican soldiers were clearly visible across the international border that separated Nogales, Arizona from Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. There were no incidents that first night, and the next day was spent in building kitchens, digging ditches and latrines, and performing all necessary duties to get the camp functioning.

This choice of a site for the camp, however, proved a disaster when a torrential rain washed much of the camp away toward the Santa Cruz River. A second location was selected atop a broad plateau about a mile north of Nogales, and a regular routine was finally established.

Drilling under Regular Army officers from the 12th U.S. Infantry, stationed at nearby Camp Stephen Little, began and most days were filled with such military drills as close order, open order and combat patrol exercises, troop reviews, rifle practice, and marching. Tyler H. Bliss, a Hartford Courant reporter embedded with the Connecticut troops, described the routine in an August 16, 1916 story: “Another day without event. Another day in that long routine of days, a day of drills, of marching, of exercises, or ordinary duties, the sort of a day of which we are getting our full share, the sort that makes soldiers, but does not make excitement. From now on, we are given to understand, most of the days will be of this sort. The novelty is over, the men are used to Arizona and Arizona is used to the men….” In his diary, Pvt. Schmith dutifully recorded some of the events that make soldiers, but not excitement: “Wed. Aug. 23 Go on rifle range 5:15 A.M. Practice on 200 & 300 Yards,” “Sat. Aug. 26 Go to range 6:00 A.M. Shoot on 300 and 500,” and “Sun. Aug 27 Go to range 7:00 A.M./shoot on 600 yrd. rng.”

Connecticut infantry troops undertook frequent marches in Arizona to increase fitness and endurance and to build resistance to the high temperatures. Corp. Merrit E. Learned Collection, courtesy of Alan D. Learned

The length of the marches in the hot sun with light packs over desert trails gradually became longer as the men became acclimated. Such marches culminated, for both the 1st and 2nd Infantry regiments, in treks to and from Fort Huachuca, a Regular Army outpost about 60 miles northeast of Nogales. On a postcard with a photo of the fort that he sent to his father, postmarked September 8, Pvt. Merritt Learned of Co. L, 2nd Regt. Infantry indicated the path the regiment had taken through the fort to their “camp about 3 miles away under the mountains.” He mentioned that some of the famed Buffalo Soldiers of the “10th Colored Calvary” [sic]were stationed at Huachuca and that “We walked about 60 miles. Feeling fine.” At the end of their hike from Huachuca back to Nogales, the 2nd Regiment rode the last few miles in trucks, perhaps the first use of motorized vehicles by a Connecticut National Guard unit.

If the hikes to Huachuca were the high point of the infantry’s days in Arizona, then Troop B’s duty in Arivaca, Arizona was the cavalry’s most exciting duty. They, too, had their routine of exercising, grooming, and watering and feeding their horses daily, and they mounted skirmish drills and reviews. On August 10, Army Brigadier General E.H. Plummer, Commander of the Nogales District, ordered Troop B’s Commander Captain John H. Davis and his men to proceed to Arivaca, a small town northwest of Nogales, to establish a camp and begin patrols along the border and among the mining camps and ranches in the surrounding area. As quoted in Origin and Fortunes of Troop B, Plummer selected Troop B “…on account of the efficiency of the organization. It has no men on sick report, its camp was maintained in a thoroughly sanitary condition and it is efficient in the performance of all duties that have been given to it.”

National Guardsmen patrolling the international border between Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. Corp. Merrit E. Learned Collection, courtesy of Alan D. Learned

For nearly two months, troopers patrolled the border, where numerous trails led into Mexico, including the “Smugglers’ Trail” to Fresnal. On August 24 they encountered 12 Mexican soldiers who had been staying in a house only 15 yards from the border and who mounted up and rode back into Mexico upon seeing the troopers. They checked on the American miners at the Oro Blanco Mining property and at the Montana mine. One of their primary duties was to guard the wagon road that led north from Mexico and was the quickest route to Tucson for any invading force. Capt. Davis stated that the territory they patrolled was so hilly that it was impassable to anything but mounted troops. During their patrolling in the Arivaca area, members of the troop carefully mapped the area.

Finally, on October 17, Pvt. Schmith recorded in his diary that the Connecticut troops “Strike tents, make up rolls and general police of camp. Leave Nogales 6:23PM in Pullman sleepers.” Within a month, all the troops had returned to their armories and had been mustered out of federal service.

On October 6 Secretary of War Newton T. Baker had written to the commanding officers of National Guard units thanking them for their service at the Mexican border. He noted that when the guard was called up, “…the lives of men, women and children along the southern frontier were in grave danger owing to formidable bandit raids from the Mexican side of the boundary.” With the guard units arrayed along the border, “…the raids ceased and the tension between the two countries began to relax.” Baker firmly believed that the presence of the guard “has made possible a peaceful solution of a difficult and threatening problem.”

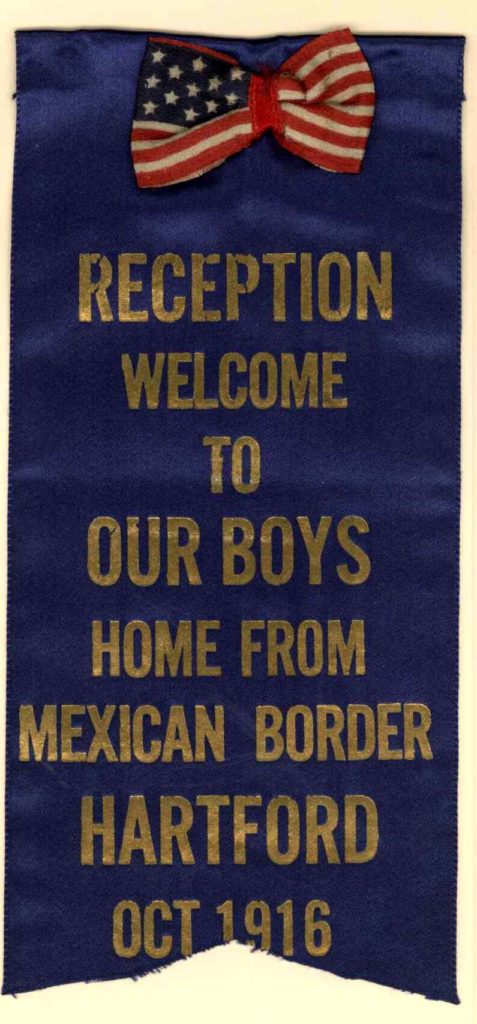

Souvenir ribbon from the welcome-home reception and parade, Hartford, October 27, 1916. Museum of Connecticut History

Upon their return from the border, the Connecticut soldiers were celebrated with large parades in Hartford and New Haven where the 1st and 2nd regiments were headquartered, respectively. Connecticut, unlike many states, did not issue medals to its Mexican border veterans, nor did it build a monument to them, as it did for its Spanish-American War veterans. The United States issued medals to both its Regular Army veterans and the National Guard soldiers who had served at the border. Many Connecticut veterans could purchase commercially made souvenirs of their time in Arizona—such as one of a variety of watch fobs with the legend “Souvenir of My Life on the Mexican Border, 1916” or a commemorative silver plated spoon with a camp scene, a fully-equipped soldier, and the legend “Mexican Border 1916,” made by The Wallingford Co., of Wallingford.

Although the Mexican border service of the National Guard has faded from memory, its importance should not be overlooked. Within six months of the soldiers’ return to their home states, the U.S. entered World War I. The first full-scale mobilization of the guard resulted in a nucleus of well-trained officers and soldiers who had experienced the rigors of military discipline in a hostile climate and received training on up-to-date military weapons and tactics. They emerged from the experience with increased status as a dependable element of national defense. Many of the Connecticut men who served along the Mexican border later distinguished themselves in combat during World War I, when the 1st and 2nd Infantry regiments were combined into the highly decorated 102nd Regiment. As the Courant reporter Tyler Bliss noted, the Connecticut troops’ Mexican border experience did, indeed, “make them soldiers.”

David Corrigan is curator of the Museum of Connecticut History and a frequent contributor to Connecticut Explored. His most recent story was “The Anti-Income-Tax Rally of 1991,” Spring 2016.