(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2004/05

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

His writing was difficult. His manner was gruff. His family unhappy and his colleagues strangers. It would appear that any gentleness was reserved for his roses and his typewriter. So why would anyone love Wallace Stevens? Because he is perhaps the most imaginative, lush, and compelling poet to have lived in the 20th century. His poetic influence extends from imagists to postmoderns drawn to his acrobatic language, and many serious painters see in his words an echo of their own vivid strokes. Furthermore, he was among a select handful in whom art and commerce cohabitated happily.

Stevens worked for decades for the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company, now known as The Hartford Financial Services Group, Inc., where he rose to the position of vice president. (Stevens headed the small-bond claims department, where he liquidated claims under defaulted bonds.) During that time he received every major American literary prize, including the Pulitzer in 1955 (the year he died), the Bollingen Prize in Poetry from Yale (1949), the Gold Medal of the Poetry Society of America (1951), two National Book Awards (1951, for The Auroras of Autumn and 1955, for his Collected Poems ), as well as honorary degrees from Columbia and Harvard. Literary critics such as Helen Vendler and Harold Bloom have bestowed upon him their highest praise, and to most contemporary American poets he is an icon. Yet during his most productive years in his adopted hometown of Hartford , he remained virtually unknown to his neighbors and an oddity to his coworkers. He deliberately kept the city at arm’s length while drawing inspiration from it.

While Hartford is justifiably proud of the literary legacy left us by Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe, Stevens, unfailingly, gets short shrift. Although Stevens’s legend has not been burnished over time to the same degree as those of his illustrious forebears, he did live and die long ago enough to have taken on an historic patina. Though he largely remains a ghost, it’s time to bring him into the light.

Born in Reading , Pennsylvania on October 2, 1879, Stevens attended Harvard (but did not matriculate) and went on to graduate from New York Law School in 1904. He began working as a reporter for the New York Tribune, but found writing about the gritty world of crime, poverty, and day-to-day human desperation unbearable and soon gave it up.

In 1909 Stevens married Elsie Kachel, also from Reading; they moved to Hartford in 1916, when he joined the insurance company as head of its surety claims department. They lived for a year at 594 Prospect Avenue before moving to an apartment at 210 Farmington Avenue, just down the street from what is now Clemens Place, then known as “Little Hollywood” because of the glamorous young professionals who lived there. During the seven years he lived there, Stevens wrote most of his first volume of poetry, Harmonium, which was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1923 when he was nearly 44 years old. It drew sporadic favorable reviews but sold few copies, and Stevens remained obscure. (In 1931 Knopf reissued Harmonium with additional poems.) The couple later moved to an upstairs apartment at 735 Farmington Avenue , where their daughter Holly was born in 1924.

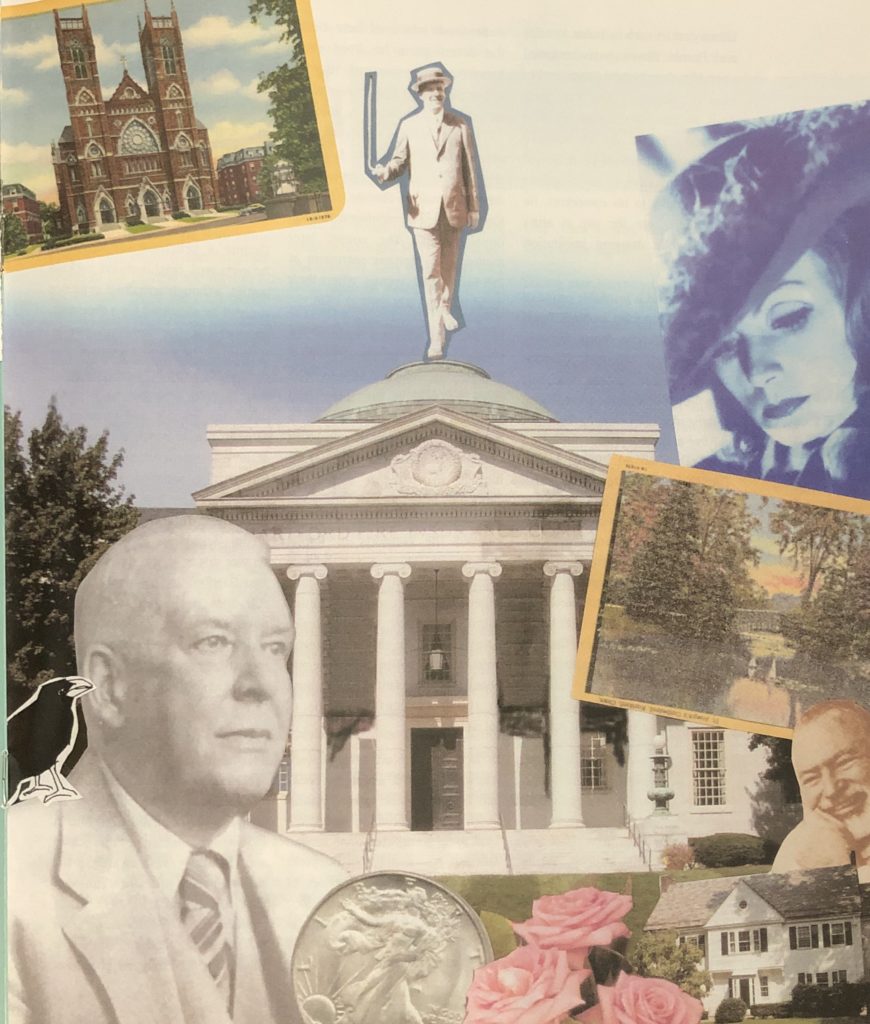

In 1932 they bought a home at 118 Westerly Terrace in the city’s West End. Records show that Stevens, who made $17,500 at the time, paid $20,000 cash for the house, a comfortable but unremarkable 1920s Colonial. It managed, like Stevens himself, to maintain an air of anonymity in an otherwise grand and eclectic neighborhood. Here, Stevens enjoyed the comforts of home, including an extensive wine cellar, a library of leather-bound books, and a collection of second-tier French paintings sent by Parisian dealer Anatole Vidal. He also tended, with great care and patience, his rose and peony beds and planted a holly bush in the front yard in honor of his daughter.

In 1932 they bought a home at 118 Westerly Terrace in the city’s West End. Records show that Stevens, who made $17,500 at the time, paid $20,000 cash for the house, a comfortable but unremarkable 1920s Colonial. It managed, like Stevens himself, to maintain an air of anonymity in an otherwise grand and eclectic neighborhood. Here, Stevens enjoyed the comforts of home, including an extensive wine cellar, a library of leather-bound books, and a collection of second-tier French paintings sent by Parisian dealer Anatole Vidal. He also tended, with great care and patience, his rose and peony beds and planted a holly bush in the front yard in honor of his daughter.

In fact, by some accounts, Stevens was so comfortable among his books and flowers that he worked assiduously to avoid becoming part of the local social scene. According to Dan Schnaidt, who founded the nonprofit Hartford Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens (HFEWS) in 1997, “Stevens was a bit shy by temperament and not always socially comfortable. This is not to say that he was antisocial. Reading his letters, it’s clear that he had a number of deep and abiding friendships. He found occasion to get together [with friends]when he traveled on business, on regular vacations in Florida, or [in]New York. His social life in Hartford was, by comparison, generally more perfunctory and business related.”

Despite a penchant for drinking, he eschewed neighborhood cocktail parties, although anecdotal evidence suggests he socialized for a time with members of the Heublein family. (Eventually he stopped responding to their invitations.) Schnaidt points out Stevens belonged to a group called the Friends and Enemies of Modern Music, which met regularly at the Wadsworth Atheneum. Mostly though, he satisfied most of his cultural cravings in New York City, far away from the scrutiny of the Hartford literati. And while each Wednesday he was driven to the Canoe Club in East Hartford (an all-male club that still does not admit women), he never varied from his diet of martinis and cold roast beef slathered with mustard; he seems not to have made many friends there.

Stevens enjoyed his most productive years as a poet in the two decades after he moved to Westerly Terrace. In 1935 Ideas of Order was issued in limited edition by Alcestis Press; the next year Knopf published it. Also in 1936 Alcestis brought out Owl’s Cloverand Stevens was awarded The Nation’s poetry prize for “The Men That Are Falling.” In 1937 Knopf published The Man with the Blue Guitar. Knopf published Parts of a World in 1942, Transport to Summer five years later, The Auroras of Autumn in 1950, and The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens in 1954.

Walking was an integral part of Stevens’s life and daily routine. He never learned to drive and famously composed poetry in his head while walking the two-mile route each day from his home in the West End to his office in Asylum Hill. He once told a reporter he enjoyed matching the words in his head to the rhythm of his footfalls. There are even stories, perhaps apocryphal, of his lumbering along, (Stevens stood over six feet tall and was overweight despite walking several miles a day) head bowed, and then suddenly backing up a few paces to repeat his steps as he worked out a particularly thorny cadence.

Sometimes, Stevens’s legendary walks took strange social turns. Edward Diemente, University of Hartford professor emeritus, recalls a tale told by a neighbor, Arthur Polley, who worked closely with Stevens at The Hartford. “Mr. Polley expressed the greatest admiration for Mr. Stevens and respected him as an outstanding insurance executive. But in other regards, Polley thought Stevens was an eccentric. One day, Polley was driving by a bus stop and saw Stevens there. Polley stopped and asked Stevens if he would like a ride. Stevens paused for a moment and then said that he would accept if Polley did not speak during the ride. They rode the entire trip in silence.”

Did Stevens cultivate an air of indifference and even withdrawal, or was he merely a shy soul stalking about in an impressive frame? Certainly his solitude and his sense of otherness emerge in “Tea at the Palaz of Hoon”:

I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw

Or heard or felt came not but from myself;

And there I found myself more truly and more strange.

From all accounts, the insurance company indulged Stevens in his second vocation. After his leisurely walk to the office, he would take notes and scraps of paper out of his pockets and transcribe-or have his secretary transcribe-his morning musings into a poem. His colleagues left him alone when he was in a reverie and knew not to ask too much about his creative life. And even after his retirement and up until shortly before he died, Stevens continued to report for work each day, and was welcomed, although one wonders how he spent his time.

Although he wrote often and thoughtfully (sometimes ponderously) about the nature of poetry, collected, along with his last poems and miscellaneous writings, two years after his death in Opus Posthumous and in an earlier and more extensive consideration of his poetics in The Necessary Angel in 1942, Stevens disliked talking about his craft. Once, at a dinner with the poet Randall Jarrell, the discussion turned to Greta Garbo, Stevens’s favorite actress. Soon, however, Jarrell turned the subject to poetry, asking Stevens why he had revised certain lines in “Sunday Morning.” According to Jarrell’s wife Mary, Stevens “began to look very vague and disbelieving, as if he hadn’t remembered whether he changed them or not. He hesitated and started to say something about ‘I don’t know why.’ Then he said, ‘Let’s talk about Greta Garbo again!'”

During rare interviews he vacillated between the terse and the obtuse. When asked once why his writing seemed obscure to so many readers, he remarked simply, “The poem must resist the intelligence almost successfully.” For all these reasons Stevens remains, nearly 50 years after his death, a supreme enigma.

And yet he is, indisputably, Hartford ‘s enigma. His poetry is filled with references to Hartford and its environs. It’s quite possible that Stevens, walking down the incline of Asylum Avenue as he did each day, saw the spires of the old Cathedral of St. Joseph and was inspired to pen these lines in “Of Hartford in a Purple Light.”

This stage-light of the Opera?

It is like a region full of intonings.

It is Hartford seen in a purple light.

A moment ago, light masculine,

Working, with big hands, on the town,

Arranged its heroic attitudes.

But now as in an amour of women

Purple sets purple round. Look, master,

See the river, the railroad, the cathedral.

Stevens was fascinated with all things European yet in his typically iconoclastic way never made the trip abroad. His poetic mind journeyed there frequently, though, and he was all too glad to take us with him, far from our quotidian existence. In his poem “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” he writes, “Misericordia, it follows that/Real and unreal are two in one: New Haven/Before and after one arrives or, say/Bergamo on a postcard, Rome after dark,/Sweden described, Salzburg with shaded eyes/Or Paris in conversation at a café.”

For all his European longings, Stevens plumbed the depths of his immediate environs, capturing both the grit of the New England industrial city and the softness of Connecticut ‘s farmland. Connecticut place names are scattered throughout his poems. In one of his best-known poems, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” he asks, “O thin men of Haddam,/Why do you imagine golden birds?” One of his favorite haunts was Elizabeth Park, which he most likely entered on the Hartford side, at the foot of Terry Road . One imagines the towering figure dodging the Asylum Avenue traffic with a scowl. His forays into the park were frequent and meditative. He wandered the paths and crossed its stone bridges with head bowed, composing lines like these from “The Plain Sense of Things”:

The greenhouse never so badly needed paint.

The chimney is fifty years old and slants to one side.

A fantastic effort has failed, a repetition

In a repetitiousness of men and flies.

Yet the absence of the imagination had

Itself to be imagined. The great pond,

The plain sense of it, without reflections, leaves,

Mud, water like dirty glass, expressing silence

Of a sort, silence of a rat come out to see,

The great pond and its waste of the lilies, all this

Had to be imagined as an inevitable knowledge,

Required, as a necessity requires.

Elizabeth Park returns in several other poems, most notably “The Hermitage at the Center” in which he writes: “And yet this end and this beginning are one,/And one last look at the ducks is a look/At lucent children round her in a ring.” Similar Elizabeth Park references occur in “Nuns Painting Water-Lilies” and “Vacancy in the Park.”

Even without the place-specific references, however, Stevens’s poetry holds a feast for both the senses and the intellect. Wallace Stevens’s sedate outer life, so suited to Hartford ‘s insurance culture, disguised-or perhaps enabled-his bold and adventurous inner life. Critics have commented that his wild, one might even say psychedelic, lines were not so much an escape from reality but a movement toward a new reality of his own making. “I think students can hear his wild or at other times carefully restrained play of sounds-that invention in language-and that can be a way into poetry’s challenges, says Denis Barone, professor of English at St. Joseph College. “At its essence his work attempts to attain the highest intellectual rigor, integrity, and purpose.”

In addition to a fertile inner poetic life, Stevens had a rich epistolary life as well. He was a prolific letter writer, and as it is speculation to assume that a poet’s poems are autobiographical, it is safer to look to his letters for insight. Holly Stevens collected and edited her father’s letters, published in 1966 as The Letters of Wallace Stevens. From the tone of their letters to one another, it is clear that Elsie was not her husband’s intellectual equal. But she was imbued with far more social grace than he, and wanted the chance to show it. Unfortunately, they rarely, if ever, invited guests to their home. Stevens had married Elsie, who was the model for the Liberty dime, for her physical beauty, and as the couple had little to sustain them over time they eventually grew distant. Despite their both being avid walkers, they took pains to stagger their walks so as to avoid leaving the house at the same time. Yet they remained married until his death.

Stevens traveled often to Florida , where he found much inspiration (and had a famous scuffle with Ernest Hemingway in 1936 which left Stevens with a black eye and a broken wrist.) In this lovely excerpt from a letter written to his wife early in their marriage, we can see the characteristic combination of the imaginative and the humdrum: “The palms are murmuring in the incessant breeze and. we are drowned in beauty. But with all that, there are a most uncalled for number of mosquitoes. My knees and wrists are covered with bites.”

Stevens’s politics were right of center, another break with traditional “poetic” thought. In a letter to a colleague he wrote of his disdain for organized labor (although he did support the working man’s right to “live decently and in security and to educate their children and to have pleasant homes.”) But as he told an acquaintance in 1940, “this is all most incidental with me and rather a ridiculous thing for me to be talking about. My direct interests are with something quite different; my direct interest is in telling the Archbishop of Canterbury to go jump off the end of the dock.”

The matter of Stevens’s religious convictions, or lack thereof, continues to be a point of debate among Stevens scholars. In many of his poems he takes an arch and cynical approach to organized religion. He is reputed not to have attended church services, although his wife occasionally attended the Asylum Hill Congregational Church. And yet, in a famous letter written by Father Arthur Hanley of the Hartford Archdiocese to Professor Janet McCann on July 24, 1977, there is an alleged conversion to Roman Catholicism. The letter, the authenticity of which some Stevens scholars doubt, is typed with strange line breaks as if to mimic a poem, and refers to Stevens’s last days, which he spent at St. Francis Hospital being treated for cancer.

Stevens died on August 2, 1955. The next day the Hartford Courant remarked that Stevens had “achieved a rare distinction as a man who led a successful and productive life in the two worlds of imagination and fact.” He was buried in Cedar Hill Cemetery , behind the Avery Heights Convalescent Home, where he had spent some time during his illness. His grave, not surprisingly, is unremarkable and hard to find among the graves of Hartford ‘s notables. Along with his former home on Westerly Terrace, it is one of the few physical places associated with Stevens. The Hartford Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens is working to change that by building a two-mile self-guided walking tour from Stevens’s home to his former office. It will feature 13 granite markers, each of which will be engraved with a stanza of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.”

Christine Palm is a columnist for the Hartford Courant, editor of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Journal, and a contributing writer to Readings, the quarterly of the Connecticut Center for the Book. She is also president of Hartford Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens.

For more information on The Wallace Stevens Walk or Hartford Friends and Enemies of Wallace Stevens events, call Christine Palm at (860) 586-8030.

Explore!

“The Surreal Side of Wallace Stevens,” Winter 2018-2019

Read more about Connecticut’s art and literary history on our TOPICS page.