by Amy L. Trout

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2006/07

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“On the walls of public buildings the heroes of legend and history come alive in glowing colors. New Haven watches, wondering and interested. The Government, it seems, has ordered a renaissance in art, and the New England city leads the way.” –Rose M. Baker, “Heroes of Legend and History Become Alive on New Haven Walls,” New Haven Register, February 11, 1934

Artists have a long history of struggling to stay employed. During the years surrounding the Great Depression, their struggle—like that of their fellow citizens—grew more acute. The federal government stepped in to help, creating the Federal Art Project. The project yielded particularly good results in New Haven.

Artists have a long history of struggling to stay employed. During the years surrounding the Great Depression, their struggle—like that of their fellow citizens—grew more acute. The federal government stepped in to help, creating the Federal Art Project. The project yielded particularly good results in New Haven.

The New Haven Museum and Historical Society is currently examining New Haven’s participation in government art patronage programs in The Federal Art Project in New Haven: The Era, Art, and Legacy, an exhibition that opened in November and runs through September 1, 2007.

The Federal Art Project (1933–1943) is a topic that could yield dozens of articles, about the various forms of artwork produced (murals, commemoratives, paintings, sculpture, educational materials, signs, ceramics, and even stained glass), the artists who created them, and their connections to time and place. This article serves as an overview of the program in New Haven; perhaps it will prompt interest in the Federal Art Project’s activities all across the state

Background

The goal of the Federal Art Project was to employ out-of-work artists. When the program was introduced, the nation was in the throes of an economic depression, with 12.8 million Americans—one quarter of the working population—out of work.1 The Roosevelt administration began an unprecedented series of federally funded relief efforts for all strata of working people. In 1933, Harry Hopkins, a close advisor of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, secured one million dollars to begin an artist work program. It was called the Public Works for Art Project (PWAP) and lasted roughly six months. Its success led to a more comprehensive program in 1935 called the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (FAP/WPA). Under these programs, the government paid artists’ salaries while local municipalities found sponsorsto pay forsupplies and materials. States were divided into regions, and each region had a volunteer administrator who worked with city government and a municipal art committee.

While employment was the official goal of the PWAP and FAP, the programs soon took on a bigger meaning for artists and administrators alike. Within months, long-term benefits, such as the formation of new relationships between artists and communities, were realized. Public art was found to inspire and uplift ordinary people whose daily lives were adversely affected by the bleak economic conditions. Such positive outcomes had been achieved in Mexico, where the government-sponsored mural movement (c. 1920–1930) had propelled artists such as Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros to international prominence and had helped forge a national identity. In the U.S., PWAP and FAP officials, local art committees, and artists themselves chose subjects that represented “America”: its landscape, history, and people. In doing so, they hoped to create a cooperative art effort that infused and empowered citizens with civic pride and encouragement.

The Federal Art Project in New Haven

The Federal Art Project operated in three regions in Connecticut: New Haven (including New Haven and Middlesex Counties), Hartford (Litchfield, Hartford, and Tolland Counties), and New London (New London and Windham Counties).3 The program was highly bureaucratic, with a hierarchy of communication and a plethora of paperwork. Obviously, the regions with administrators who could handle such burdens were the most successful. A supportive city government was also a key to success as appropriate public buildings for the art work, such as schools and libraries, had to be found. City officials and administrators also had to cooperate with a local art committee that conceived of ideas for projects and reviewed submissions. Finally, to make the program work, a community of artists had to be available.

New Haven had just such a combination. The presence of the Yale University Art Gallery and Yale School of Fine Arts provided the region with a contingent of knowledgeable art scholars as part of its faculty. The school created an able body of talented—and largely unemployed—graduates. Theodore Sizer, associate director of the Yale Art Gallery, became the first administrator of the region’s P WAP, serving from 1933 through 1935. Colleague Way l and Williams, also from the Yale Art Gallery, took over and later became the state administrator for the FAP. The state’s WPA office was located in New Haven at 63 Dwight Street. The fact that the city was home to both a prestigious art school and the state’s WPA office gave it an advantage over other communities.

The PWA P and FAP were strongly supported by the city’s government , headed up by Democratic Mayor John W. Murphy (1873–1963). Murphy was the son of Irish immigrants who had worked first in the city’s cigar factories and then for its labor unions before entering politics. His working-class background helped him understand his citizens’ needs during the Depression. Although Yale e xpanded its campus during the Depression, helping keep some of the building trades alive and well, the rest of the city felt the same hard times as the rest of the nation. Production was down in the factories, unem-ployment at an high, and Mechanics’ Bank (the city’s second largest bank and the one holding the city’s funds) failed in 1932. By the end of that year, New Haven’s municipal deficit topped $1 million, with $825,000 going to city relief efforts. Murphy had to convince city employees, banks, industry, and the average citizen that New Haven was going to be okay. When the New Deal’s Civil Works Authority (CWA) authorized 3,900 jobs for New Haven in 1933, it was good news for both Mayor Murphy and the city’s uemployed.

The PWAP fell under the jurisdiction of the CWA, and New Haven threw its full support behind the new government art program. A portrait of Mayor Murphy was Project #1. The mayor paid for the canvas and supplies, and the government paid the salary of the artist, Ferdinand Maiorano. In fact, many of the PWAP’s early projects were portraits of civic leaders (past and present) painted in oil or carved in wood and marble. These portraits were destined to grace the hallways of city buildings, such as City Hall and the Hall of Records, and schools and administration buildings. Although these portraits are some of the least glamorous and, in many cases, least remembered, they memorialized city officials who dedicated a significant portion of their lives to New Haven.

The PWAP fell under the jurisdiction of the CWA, and New Haven threw its full support behind the new government art program. A portrait of Mayor Murphy was Project #1. The mayor paid for the canvas and supplies, and the government paid the salary of the artist, Ferdinand Maiorano. In fact, many of the PWAP’s early projects were portraits of civic leaders (past and present) painted in oil or carved in wood and marble. These portraits were destined to grace the hallways of city buildings, such as City Hall and the Hall of Records, and schools and administration buildings. Although these portraits are some of the least glamorous and, in many cases, least remembered, they memorialized city officials who dedicated a significant portion of their lives to New Haven.

If portraits of civic leaders didn’t register much public reaction, the murals painted in city buildings such as schools and the main branch of the public library did. The murals’ themes fell in to several familiar categories: local history, commemorative events, children’s literature, and “learning.” These themes appealed to administrators and the local art committee be cause they could be told through pictorial narratives and be easily understood by people of various ages, backgrounds, and levels of education. The murals were painted in plain view of school children and the public and garnered much attention around town.

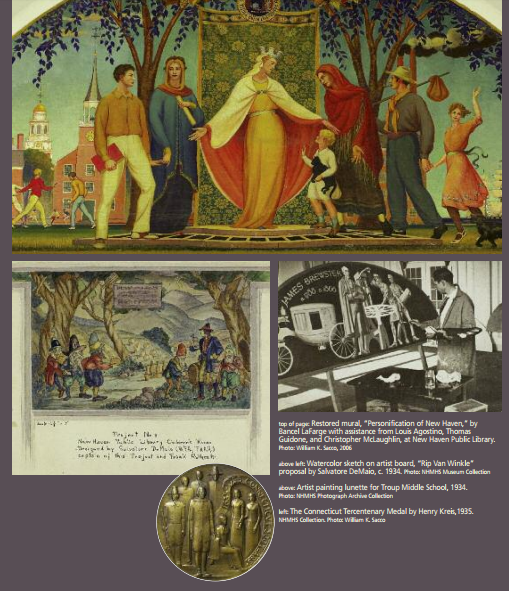

In the children’s room at the New Haven Public Library, scenes from Washington Irving’s classic Rip Van Winkle were painted as frescoes. As the mural was being painted in 1934, a New Haven Register reporter noted, “The children stand wide-eyed and speechless and watch the three painters in their green smocks, bringing the magic figures to life.” As other murals began to appear around town, publicity about them grew, and New Haven became a “model” of sorts for other communities whose art programs hadn’t progressed quite as quickly. A 1934 article in the Christian Science Monitor captured the community spirit of the venture: “The New Haven Public Works of Art Project has become a community affair. Mayor Murphy helps. The Board of Education votes $500 to purchase artists materials. Everyone is interested. Everyone contributes, willingly, eagerly. Everybody studies designs and digs in to local history. The whole community becomes mural-conscious. Groups of school children supplementt heir academic work with observation of the painters occupied with the various decorations.” The open artistic process, combined with city cooperation and a clearly understood visual image, made for a positive public reaction to the murals.

The Artists

The one thing the artists working for FAP had in common was that they all needed a job. Most had formal education that included training at a reputable art school. In the New Haven region, many artists had studied at the Yale School of Fine Arts. Being that Sizer taught at Yale and administered the local PWAP office, it was inevitable that he would draw from his own students in selecting artists. Although he denied any favoritism, it is clear that the program benefited from close ties with the art school. Still, Sizer went to great lengths to show that the artists working under him were“ typically American” and not representative of an elite class. His office compiled figures claiming that of the 42 artists at work in 1934, 22 were characterized as “American,” 13 “Italian,” 3 “Polish,” 2 “German,” and 2 “Slavic.” 9 There were no African-American artists listed, and only a handful of women.

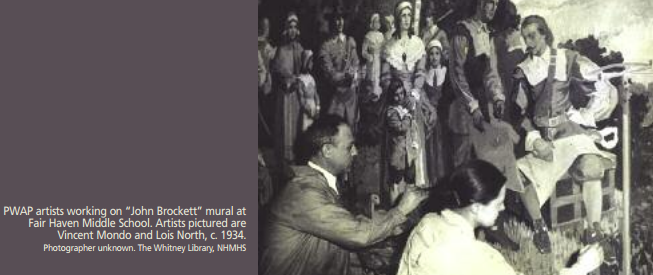

The most prolific female artist in the New Haven region was Lois North, who attended New Haven and Orange public schools before graduating from Yale School of Fine Arts in 1930. Lois first worked as an assistant but later headed mural projects of her own in New Haven (“Life of Hiawatha” at Edgewood School), Bethany (“Map of Old Bethany” at Bethany Community School), and Ansonia (“David Humphrey” at Ansonia High School). Other women artists include Jeanette Brinsmade, Alexandra Darrow, and Lyndell Schwarz. During the later FAP period, around 1938, Laicita Worden Gregg of Wilton, Connecticut, painted a mural of “The Regicides” for Woolsey School in the Fair Haven section of New Haven.

The artists were paid modest salaries. Under PWAP, the pay scale ranged from $10 to $37.50 a week, depending on the artist’s rank as an assistant or head artist. Pay could also be reduced if the economic situation in the artist’s household changed. For example, if the artist’s spouse got a job, then the artist’s government salary could be reduced. Other federal funding agencies (FERA and TRAP) had slightly different pay scales, but they were all based on a combination of artistic skill and economic need.

Cultural Themes Form a Community Identity

The larger role that the PWAP and FAP played in communities such as New Haven is illustrated by the cultural themes of the murals and the era in which they were created. Although the 1930s is largely thought of as the decade of the Great Depression, in Connecticut the 1930s can be regarded also as a decade of historical celebration. New Haven and Connecticut both commemorated their 300th anniversaries during the decade. The festivities required years of planning and preparation. City and state officials tried to make the celebrations as inclusive as possible, welcoming business, government, academia, and average citizens. The tercentenaries were designed to recognize the region’s rich historic past, particularly its colonial heritage. This preponderance for all things colonial fit into a decades-old movement known as the Colonial Revival (c. 1876–1930s) in Connecticut and throughout the nation, which saw the emergence of hereditary societies such as the Daughters of the American Revolution, a revival of interest in colonial architecture and decorative arts and their preservation, and the celebration of famous historical figures and events.

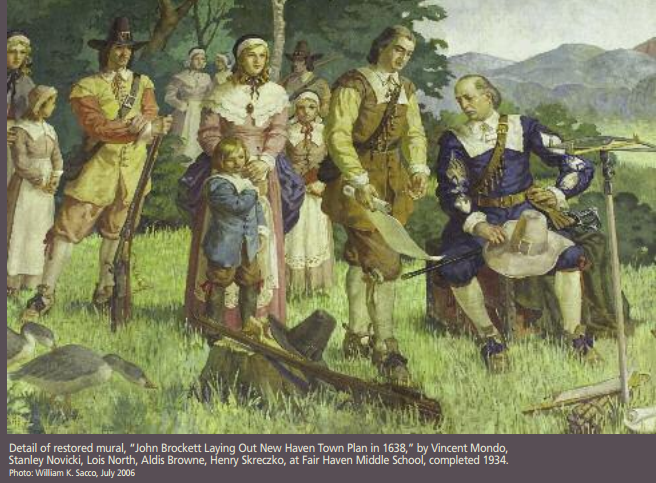

The arrival of the government patronage of the arts program coincided with this era of historical celebration, and that meant that murals glorifying local history ended up on the walls of public places. Murals with colonial themes featured local heroes such as Roger Sherman (signer of all fourfounding documents and New Haven’s first mayor), Nathan Hale (Connecticut native, Yale graduate, and Revolutionary War martyr), John Brockett (Puritan surveyor and for years considered the architect of the city’s “nine squares”), John Davenport and Theophilus Eaton (the founders and leaders of the New Haven Colony), and the “Regicides” (Puritan judges who, after condemning Charles I to death, were later pursued by agents of Charles II and found refuge in New Haven).

Learning about local heroes fit into the 1930s public school curricula in New Haven. What better way to learn about these figures than to see them depicted in large, dramatic murals on the walls of school classrooms, libraries, and hallways? As students passed them, the murals served as daily reminders of the city’s proud colonial past.

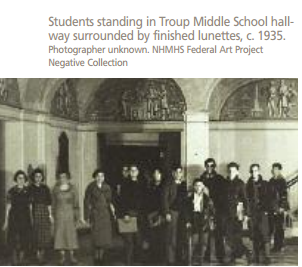

New Haven also celebrated its industrial history of innovation. Ten lunettes in the entryway at Troup Middle School (now Troup Magnet Academy of Science) featured inventor Eli Whitney, Samuel F. B. Morse, Thomas Sanford, Eli Whitney Blake, and Charles Goodyear along with arms manufacturer Oliver Winchester, hardware maker Joseph Sargent, clockmaker Chauncey Jerome, carriage maker James Brewster, and architect Ithiel Town. Hard work and “Yankee ingenuity” were very much part of the lore of New England in the early industrial age. New Haven had been a manufacturing mecca in the 19th century; promoting its famous inventors and industrialists reinforced this identity during a time of economic uncertainty.

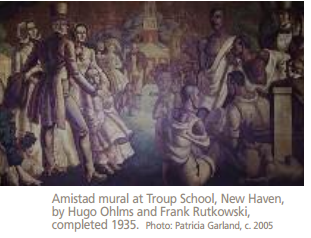

At the prodding of antiquarian George Dudley Seymour, who served on the local municipal art committee, one mural depicted perhaps one of the most challenging local historical events, that of the rebellion and trial of the captives aboard the ship The Amistad (1839–1842). Although the event is well known to many today, that wasn’t the case in the 1930s. The scene Seymour proposed, and the one ultimately chosen, was one of the African captives “exercising” on the New Haven Green while awaiting trial. While referencing the Green and Center Church, the scene is weak in chronicling the great historical debate of the period, slavery vs. abolition. The timeless, inspirational message of the incident—the struggle for justice and freedom—is also unclear.

At the prodding of antiquarian George Dudley Seymour, who served on the local municipal art committee, one mural depicted perhaps one of the most challenging local historical events, that of the rebellion and trial of the captives aboard the ship The Amistad (1839–1842). Although the event is well known to many today, that wasn’t the case in the 1930s. The scene Seymour proposed, and the one ultimately chosen, was one of the African captives “exercising” on the New Haven Green while awaiting trial. While referencing the Green and Center Church, the scene is weak in chronicling the great historical debate of the period, slavery vs. abolition. The timeless, inspirational message of the incident—the struggle for justice and freedom—is also unclear.

The mural’s blandness rendered it harmless to those worried about “controversial” subjects, but it also made it somewhat forgettable in later Amistad celebrations around the state. Despite its lack of drama, the mural is noteworthy for paying tribute to a historical event that was little known at the time. It’s also the earliest mural commemorating the incident, completed circa 1935, a few years before Hale Woodruff painted his famous Amistad murals in the Savery Library at Talladega College in 1939.

While murals would dominate the public’s attention, many other forms of art were executed by PWAP and FAP artists. During the tercentenary years, commemoratives such as medals, stamps, and a coin were created by artists paid through federal patronage programs. FAP artists also contributed their talents to posters, programs, and other ephemera. In June of 1938, as part of New Haven’s tercentenary celebration, FAP artwork was on display at the city’s “Progress Exposition,” with an estimated attendance of 12,000 citizens.

Possibly the most forgotten aspect of the FAP, the easel painting program generated thousands of works of art for the walls of government and education office buildings after 1935. Although this medium offered a little more freedom of expression for artists, most of the paintings still represented traditional subjects (landscapes, still lifes, and portraits) and styles. The one exception was Waterbury native George Marinko, who painted in a surrealist style. Few of these paintings remain in their original location; some are now in museums or private collections. Many more were simply lost.

Preservation and Legacy

Although some of the art created by the Federal Art Project is gone, stunning examples of murals, commemoratives, educational materials, sculpture, and portraits remain extant around New Haven. Murals in two New Haven schools recently received conservation treatment; another school, Troup Magnet Academy of Science, is currently undergoing renovations that include the conservation of close to 30 murals and lunettes funded through the FAP.14 The New Haven Museum and Historical Society recently restored a salvaged FAP mural in its collections. There is an increasing awareness that these works of art were created from a unique program in American history and carry with them cultural content about New Haven and about American life during the Depression. Perhaps a rejuvenated “mural consciousness” lies ahead!

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut art history on our TOPICS page.