By Jessica D. Jenkins (c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2016

By Jessica D. Jenkins (c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2016

As spring primaries draw near and campaigning heats up for the November general elections, Connecticans across the state will find themselves swimming in a sea of campaign ads. According to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, female voters in the United States have voted in higher numbers than men in every presidential election since 1980. Yet a century ago most female citizens in our nation were barred by law from voting. It was not until 1920, after the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, that women would universally receive the right to vote in all elections. (Women in some parts of the U.S. had been able to vote in all or some elections as early as 1869.) In Connecticut suffragists had been fighting for women’s voting rights for decades. Their efforts and perseverance put Connecticut women on the political stage and engaged the state in a national story that is still being told today.

Connecticut’s push for women’s voting rights got underway in the late 1860s when Frances Ellen Burr of Hartford collected signatures on a petition in support of women’s right to vote. As noted in History of Woman Suffrage by Susan B. Anthony (1886), Burr stated in an 1885 letter to Anthony that as a leader of suffrage in the state she “was pretty much alone here in those days.” Through her efforts, though, a bill regarding women’s suffrage was presented to the Connecticut House of Representatives for the first time in 1867. Although the bill was voted down, 111 to 93, the suffrage bug had bitten a group of Connecticut’s politically-minded citizens, and in Hartford in 1869 the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was formed at the state’s first suffrage convention. According to Carole Nichols in Votes and More for Women: Suffrage and After in Connecticut (The Haworth Press, 1983), Connecticut’s suffragists, like other advocates across the nation, argued long and hard for their cause to legislators and the general public. They regularly pressed the state legislature to consider suffrage bills, prepared petitions, and spoke at legislative hearings.

Looking to create wide appeal to pressure lawmakers, Connecticut’s suffragists argued that as citizens they were entitled to the vote as a fundamental right. They also argued that tax-paying women needed the vote to protect their property, working women needed the vote to influence labor conditions, mothers needed the vote to address moral conditions for the benefit of their children, and all women needed the ballot because they and men were equally responsible for civic justice. Connecticut’s suffragists did not only make their case to the well-educated white women of financial means who made up their leadership and a majority of their membership. They also appealed to factory workers and immigrants across the state who wanted a voice in protecting their rights as well.

Looking to create wide appeal to pressure lawmakers, Connecticut’s suffragists argued that as citizens they were entitled to the vote as a fundamental right. They also argued that tax-paying women needed the vote to protect their property, working women needed the vote to influence labor conditions, mothers needed the vote to address moral conditions for the benefit of their children, and all women needed the ballot because they and men were equally responsible for civic justice. Connecticut’s suffragists did not only make their case to the well-educated white women of financial means who made up their leadership and a majority of their membership. They also appealed to factory workers and immigrants across the state who wanted a voice in protecting their rights as well.

Although dominated by women, the movement also had male supporters. Alice Stone Blackwell (editor of the Woman’s Journal, a popular women’s-rights publication) wrote, “From the very beginning … courageous and justice-loving men have stood by the women and have been invaluable allies in the long fight.” Likewise, from the time of the CWSA’s founding, Connecticut’s male suffragists became active voices for the cause. In Litchfield, local lawyer George A. Hickox showed his support by becoming a member and signer of the group’s constitution. In 1870 Hickox served as a vice president of the CWSA and published a pamphlet for the organization called Legal Disabilities of Married Women in Connecticut. As editor of the Litchfield Enquirer (the town’s newspaper), Hickox regularly published stories regarding universal suffrage and kept the topic in the local community’s eye.

After working for many years, suffragists began to see a mixed bag of results. Small victories were won when Connecticut women gained the right to vote for school officials in 1893 and on library issues in 1909. Yet by national standards these triumphs paled in comparison to the adoption of full women’s suffrage by the Wyoming Territory in 1869, Utah’s passage of the right in 1870, Colorado’s approval in 1893, and Idaho’s in 1896.

By the first years of the 20th century women in Connecticut had gained a number of non-voting rights, too. They could now be elected and appointed to state and local offices and could serve as school trustees, public librarians, police matrons, notaries public, and assistant town clerks. In 1877, married women in Connecticut gained the right to control their own property—largely through the efforts of suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker and her husband John Hooker. In 1882 women were admitted to the practice of law [See “Breaking the Legal Barrier,” Spring 2010], and by 1900 women had been admitted to Wesleyan University, Hartford Theological Seminary, and Yale University, as Nichols notes.

Despite these successes, the CWSA began to wane in the first decade of the 20th century. In 1906 the organization had only 50 members, and only two other suffrage groups existed in the state. Frustration sank in when it became apparent that women’s ability to vote in school elections made little difference. As Nichols points out, party leaders controlled the selection of candidates and the outcome of these elections. Adding insult to injury, the 1909 law allowing women to vote on library issues was never put into practice. Keeping morale high in the face of obstruction by corrupt politicians became difficult, and long-active suffragists became weary. This slowdown in momentum signaled a need for a change in command.

Bolstered by the ideas of the reform-minded progressive era, a new generation of energetic middle- and upper-class suffragists came forward. These new leaders were ready to face down Connecticut’s entrenched state government, which was dominated by a small group of rural Republicans. This well-established political machine had pro-business, fiscally conservative, anti-labor tendencies, including, as Nichols points out, a record of working against suffrage and prohibition.

After a visit by British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst to Hartford in 1909, Hartford’s Katharine Houghton Hepburn (a local social activist with a 1900 M.A. from Bryn Mawr College) took on the presidency of the CWSA in 1910. Hepburn was joined in leadership roles by such suffragists as Caroline Ruutz-Rees (headmistress of Rosemary Hall School in Greenwich, with a 1910 Ph.D. from Columbia University), Katharine Ludington (a portrait painter in Old Lyme and future founding member of the League of Women Voters), Emily Pierson (a teacher at Bristol High School with a 1908 M.A. from Columbia), and Valeria Hopkins Parker (a physician from Greenwich with a 1902 M.D. from Hering Medical College). These women rejuvenated the fight, and like the suffragists before them they argued that women’s natural rights included equal participation in government. They also showed interest in a wide range of issues including child labor, prostitution, political corruption, and fair work regulations.

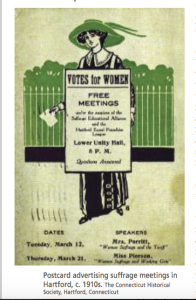

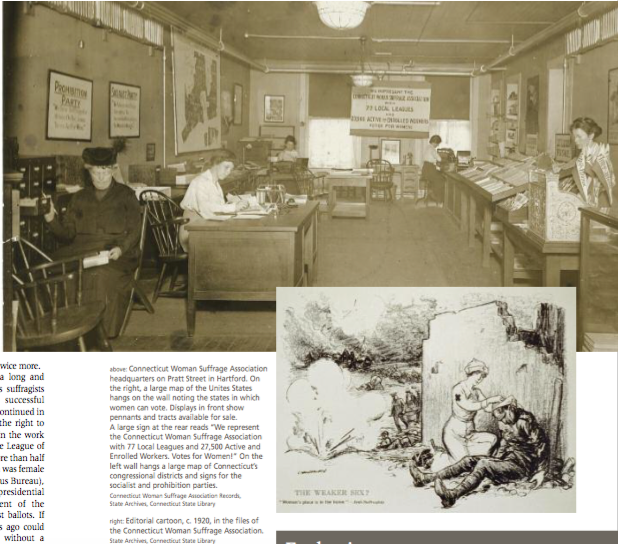

The new energy quickly took effect as the CWSA organized leafleting campaigns, petition drives, meetings, and other public tactics to garner support for their cause. Looking to create more diverse backing, suffragists worked to form a broader coalition. In one such effort, the CWSA embarked upon a month-long automobile tour of Litchfield County—an anti-suffrage stronghold—in August 1911. With their car decked out in pennants and banners reading, “Votes for Women,” the suffragists stopped in 32 communities, where they held free meetings featuring speakers prominent at the state and national levels. Despite strong opposition, seven new suffrage leagues formed in communities across Litchfield County, including Norfolk, Sharon, Harwinton, Canaan, and Salisbury. It was reported at the CWSA’s September 1911 board meeting that of the 5,000 individuals who attended the events, 964 had signed petitions in support of women’s suffrage.

Not all women supported women’s right to vote. In 1910 the Connecticut Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was formed to preserve women’s non-political role in society. Led by Grace G. Markham of Hartford, these anti-suffragists also appeared before legislative committees, distributed leaflets and pamphlets, and hosted meetings and debates. Susan Marshall, in Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in in the Campaign Against Woman Suffrage (University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), notes that the “Antis,” as they were known, did not believe that women were physically or temperamentally fit to vote. They argued that men were capable of conducting government for both sexes, that women suffered from no injustice that the vote would fix, and that their having the right to vote was simply unnecessary.

Although they presented a robust program, the Antis did not pose the greatest obstacle to women’s suffrage. The women’s suffrage movement’s strongest opponent was the state’s long-standing Republican machine, led by GOP party boss John Henry Roraback. According to Sara Hunter Graham in Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy (Yale University Press, 1996), despite growing industrialization and an ever-increasing immigrant and labor population, Connecticut’s lawmakers showed limited sympathy toward labor regulations and regularly voted down a wide range of progressive bills. The Republican machine also strongly opposed the advancement of women and their causes.

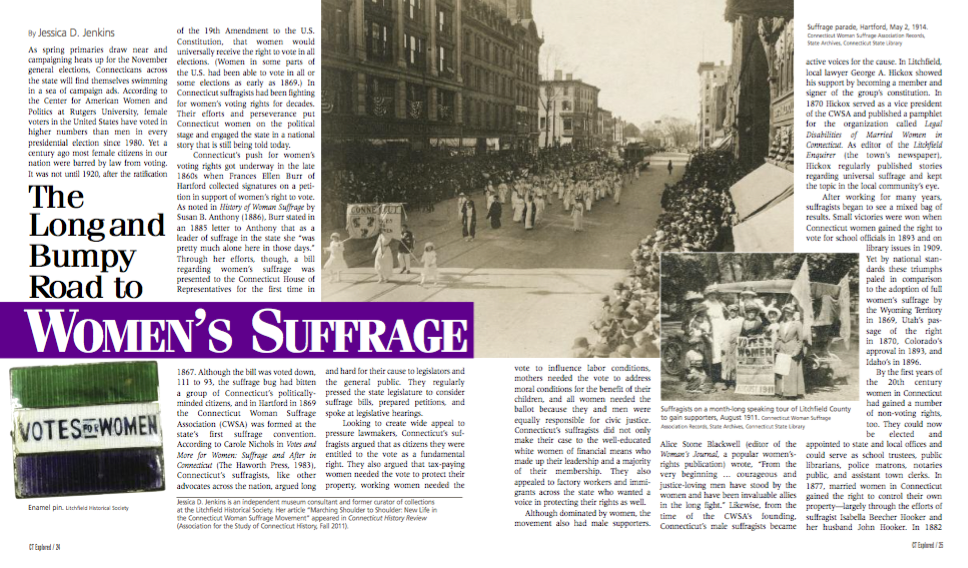

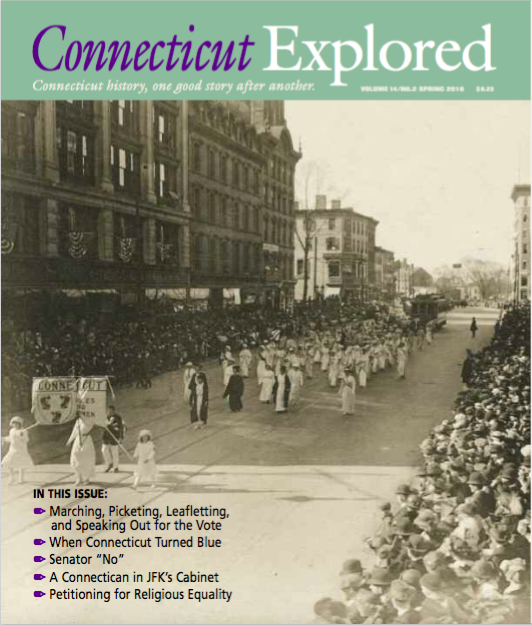

In 1914 the CWSA spearheaded the planning of Connecticut’s first suffrage parade. The May 2 event corresponded with suffrage demonstrations nationwide. Thousands of men, women, and children turned out in Hartford to watch the spectacle. The parade boasted 2,000 participants riding on floats and in automobiles, marching in costumes, and carrying banners. Cameramen positioned at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Bushnell Park captured moving images of the parade. Later The Naugatuck Daily News reported that the film footage, shown in theaters across Connecticut, was a hit and viewers were anxious “to recognize friends and acquaintances.” The parade resulted in a surge of activities around Connecticut that brought more exposure to the cause and expanded suffragists’ backing across the state, as I noted in “Marching Shoulder to Shoulder: New Life in the Woman Suffrage Movement” (Connecticut History, 2011).

By the end of 1911, 14 new local leagues had been established around the state. In May 1914 suffrage clubs for both men and women stretched from Sharon to Groton, from Putnam to Stamford. The efforts to reinvigorate the suffrage cause had worked, and in 1917 the CWSA’s membership reached 32,000 (of a state population of approximately 1.2 million people). The second decade of the 20th century saw automobile tours of Windham, Tolland, and Middlesex counties, a suffrage parade in New Haven in 1916, booths at the Connecticut state fair in Hartford, and outdoor gatherings known as “sunset suffrage meetings.”

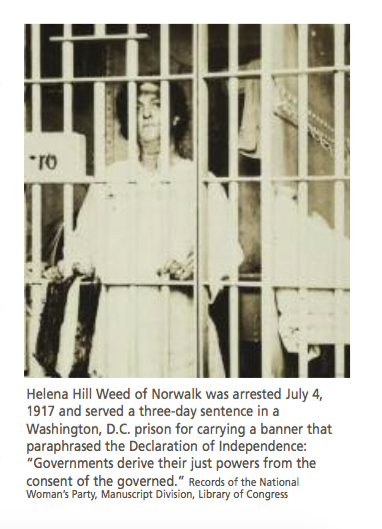

By the end of the 1910s radical groups such as the Congressional Union and National Woman’s Party had made inroads in Connecticut, too. The Congressional Union, founded in 1913 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., drew its inspiration from the militant British suffragette movement. Unlike the more conservative CWSA, which campaigned for state legislation, the Congressional Union set its sights on lobbying directly for a federal constitutional amendment. Their strategy was to blame President Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic party for the continued absence of a universal suffrage amendment. Their tactics included picketing at the White House and elsewhere, which activity resulted in arrests, imprisonment—and front-page headlines.

By the end of the 1910s radical groups such as the Congressional Union and National Woman’s Party had made inroads in Connecticut, too. The Congressional Union, founded in 1913 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., drew its inspiration from the militant British suffragette movement. Unlike the more conservative CWSA, which campaigned for state legislation, the Congressional Union set its sights on lobbying directly for a federal constitutional amendment. Their strategy was to blame President Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic party for the continued absence of a universal suffrage amendment. Their tactics included picketing at the White House and elsewhere, which activity resulted in arrests, imprisonment—and front-page headlines.

With support from suffragists such as Hepburn, a Connecticut branch of the Congressional Union was formed in 1915. By 1917 the organization had become the Connecticut branch of the National Woman’s Party. That same year disagreements as to strategy and tactics caused several of the CWSA’s prominent leaders, including Hepburn, to step down from the organization’s board in favor of becoming active members of the National Woman’s Party (NWP). While most of these women would retain their membership in the CWSA, they went on to adopt the radical campaigning tactics of the NWP.

Between 1917 and 1919, Nichols notes, 14 Connecticut suffragists were imprisoned for picketing in Washington, D.C., and acts such as protests and hunger strikes became part of the NWP’s regular operations. Helena Hill Weed of Norwalk, one of the first female geologists in the United States, a vice president of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and daughter of Republican U.S. Representative Ebenezer Hill, was arrested for picketing and served three days in a Washington, D.C. prison in 1917. In 1918 she was arrested twice more, once serving a prison sentence of 15 days.

By 1914 Roraback, head of the Republican State Central Committee, found himself in a position of ultimate authority. With virtually every candidate and patronage position cleared by him, even Democrats (who commonly were the only source of sympathy for suffragists) found it fruitful to side with the Republican machine. As practically all government entities, down to the local level, adhered to the message delivered by state leaders, it became increasingly impossible for suffragists to gain legislative support. As Nichols points out, even many of the state’s major newspapers, such as The Hartford Courant, published from a Republican viewpoint. This meant a heavy anti-suffrage bias in the media.

But suffragists kept their eye on the prize. In April 1917 the United States entered World War I. In the midst of patriotic obligation, women’s suffrage seemed to slip from the public eye. But suffragists had plans to use the conflict to position themselves in a way they had not yet tried.

But suffragists kept their eye on the prize. In April 1917 the United States entered World War I. In the midst of patriotic obligation, women’s suffrage seemed to slip from the public eye. But suffragists had plans to use the conflict to position themselves in a way they had not yet tried.

With the nation’s entrance into the war, suffragists saw an opening to gain the support of President Wilson and the public. They aimed to align suffrage with women’s work in war service. In Connecticut as elsewhere, suffragists spent countless hours raising money for overseas hospitals, promoting food conservation, and, in Litchfield, for example, working alongside anti-suffragists on the Liberty Loan campaign. [See also “Greenwich Women Face the Great War,” Winter 2014-2015.] These efforts were meant to communicate to the public that women’s suffrage was patriotic and that women were just as willing to share the burden of war as were the men of their country. In a bold move, members of the NWP, such as Weed, risking being perceived as unpatriotic, continued to picket the White House and frequently reminded the government about its hypocrisy in promoting democracy overseas while denying women the right to vote at home.

After years of resistance and vocal opposition, in 1918 President Woodrow Wilson announced his support of women’s suffrage legislation. While his words did not spur an immediate effect, the political balance began to shift, and in 1919 the United States Congress approved a universal suffrage amendment. Before the legislation could be adopted, three-quarters of the nation’s states would need to ratify it. Every month between June 1919 and March 1920 more states signed on, and by April only one more state was needed to put the legislation into effect.

With its active state-level organizations and strong local suffrage leagues in place, Connecticut drew attention and anticipation from around the nation. Connecticut’s suffragists had also been optimistic following the election of a progressive-minded majority to the general assembly in 1918. Their hopes diminished, however, when the legislature adjourned in 1919 without acting on the issue. Connecticut’s governing body would not meet again until 1921. In an attempt to apply pressure and persuade politicians of the inevitability of women’s suffrage, activists across Connecticut distributed leaflets criticizing the legislature’s refusal to sign the bill. Republican governor Marcus H. Holcomb was petitioned to call a special session of the legislature to vote on the issue, but he refused. The CWSA’s full-scale assault on the governor was bolstered by local committees, which held public meetings and rallies and issued press releases. Despite every effort to force state support and impose a special session of the legislature to consider the amendment, the official resistance of politicians and Connecticut’s Republican Party remained strong.

In August 1920 Tennessee ratified the amendment, assuring its federal adoption. In a reverse of its earlier stance and with an eye toward the November elections that year, Connecticut’s legislature finally convened in special session on September 14 and ratified the amendment; it met again on September 21 and reaffirmed the amendment twice more.

In August 1920 Tennessee ratified the amendment, assuring its federal adoption. In a reverse of its earlier stance and with an eye toward the November elections that year, Connecticut’s legislature finally convened in special session on September 14 and ratified the amendment; it met again on September 21 and reaffirmed the amendment twice more.

Although theirs was a long and bumpy road, Connecticut’s suffragists saw their cause to its successful completion. Their passion continued in the years after passage of the right to vote and can still be seen in the work of such organizations as the League of Women Voters. In 2014 more than half of Connecticut’s population was female (according to the U.S. Census Bureau), and during the last presidential election, nearly 74 percent of the state’s 2 million voters cast ballots. If the suffragists of 100 years ago could speak today, they would without a doubt be telling every woman to fire up her engine and head to the polls this November.

Jessica D. Jenkins is an independent museum consultant and former curator of collections at the Litchfield Historical Society. Her article “Marching Shoulder to Shoulder: New Life in the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Movement” appeared Connecticut History Review (Association for the Study of Connecticut History, Fall 2011).

Read more stories from the Spring 2016 issue