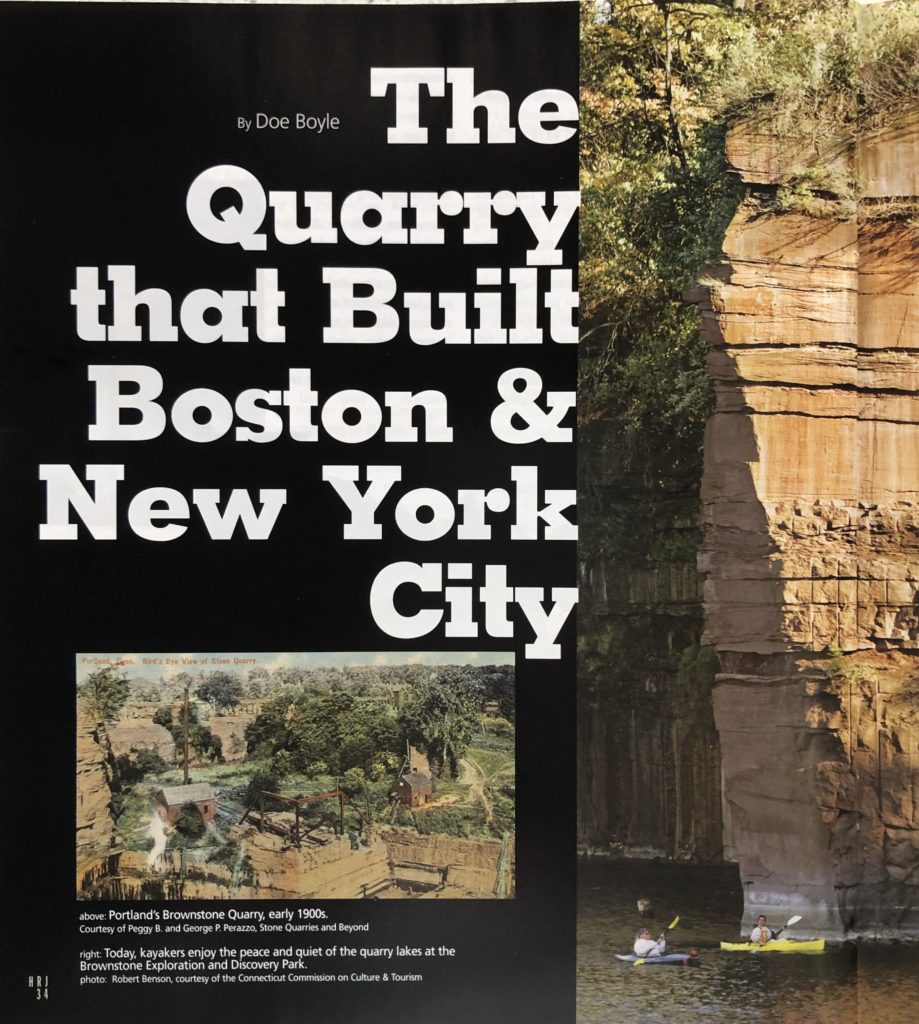

left: postcard, “Bird’s Eye View of Stone Quarry, Portland, Conn.”, early 1900s. Courtesy of Peggy B. and George P. Perazzo, Stone Quarries and Beyond. right: Kayakers at Brownstone Exploration and Discovery Park. photo: Robert Benson, courtesy of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism

by Doe Boyle

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

A paddler making her way past the great bend in the Connecticut River near Middletown would never guess, with a glance toward the eastern bank, that just yards away—a bit north of the bridge to Portland and beyond the oil tanks of that town’s industrial area—lies one of the nation’s most intriguing historic landmarks. The paddler who pauses here, however, and climbs the embankment will discover two huge stone basins with massive walls of a distinctive chocolate-brown hue. This is the Portland Quarry, where Connecticut’s famous brownstone has been quarried for more than 300 years.

In the early Mesozoic era—220 million to 195 million years ago—sandstone was deposited here in continental rift basins that formed when the super-continent of Pangaea (or Pangea) began to break apart. The Atlantic floor started to spread, and the Eastern Border Fault formed a wedged-shaped depression labeled the Connecticut rift valley. Over time, this valley filled with sediments eroded from the ancient Eastern Highlands. The brownstone that today rings the rims and forms the floors of the Portland quarry is part of the youngest layers of sediment that settled in the rift zone. This sedimentary material, known here as the Portland Formation, was 900 to 1,500 feet thick, and the brownstone—before 10 million cubic yards of it was hauled away —lies in individual planar beds that vary from 2 to 18 feet in thickness, 20 to 100 feet in width, and 50 to 150 feet in length, according to research compiled by Alison C. Guinness, in “Heart of Stone: The Brownstone Industry of Portland, Connecticut,” (The Great Rift Valleys of Pangea in Eastern North America, Columbia University Press, 2003). Coarse grains of a sand composed of mica, quartz, and feldspar created this material, classified by geologists as arkose sediment. In Portland, the arkose sediment gets its characteristic deep-brown hue from the oxidation of ferric oxides also present in this layer.

Over time, the rock broke into immense blocks, creating a system of natural joints and cracks perpendicular to one another. This tidy arrangement, bedded nearly horizontally, made quarrying much more convenient when that industry began. The cocoa-colored rock was nicknamed freestone—a nod to the ease with which it could be wrested from the earth.

From Artisan to Big Business

Laid out in 1650, the English settlement of Mattabeset, renamed Middletown in 1653, centered on the western elbow of the big bend in the Connecticut River, though land grants were parceled out after 1652 on the eastern bank. The settlers soon recognized the usefulness of the brownstone, visible in cliffs overhanging the Connecticut River’s banks, and ferried across the river from time to time to gather the loose stone that fell to the ground. The stone was used in the foundations and chimneys of a growing number of newcomers’ dwellings. The town fathers also recognized the brownstone’s value and in September 1665, according to J. S. Bayne’s “Town of Portland,” (in History of Middlesex County, Connecticut, J. B. Beers & Co., 1884), passed a town ordinance requiring “that whosoever should dig or raise stone at ye rocks on the east side of the Great River…shall be responsible to ye towne 12 pence per tunn for every tunn of stone that he or they shall dig.”

Stonecutter James Stanclift is believed to have been the first European to live on the eastern bank of the river. In 1686, the town granted him “a parcell of land upon the rocks” in payment for his work as a mason; by 1696, he owned six acres of prime quarry land. Stanclift became widely known for his artistry as a gravestone maker, developing a signature style in the shapes of his markers and the forms of his lettering. After Stanclift’s death in 1714, his sons William and James Stancliff (having modified the spelling of their last name) inherited his property and carried on as stonecutters, with some competition from Thomas Johnson of the “Upper Houses” of Middletown, now Cromwell.

By the turn of the 18th century, the fallen rock at the base of the cliffs had grown scarce, the English population had increased, and the Wangunk, who generally kept to the eastern side of the waterway, had gradually been pushed from their homelands. By 1714, most of the land available to the English was on the east side of the river. In 1715, true quarrying of the face of the outcroppings began after the town passed an ordinance empowering the town selectmen to lease and grant use of the quarries. Residents of what was by then known as East Middletown were still allowed to take stone for their personal needs, but outsiders paid “20 shillings a stone for every stone” transported away from what was called, by 1726, the Town Quarry.

By mid-century the popularity of the stone-cutting work produced by the Stancliff brothers and Johnson increased as demand grew for elaborate personalized gravestones. This led to more invasive quarrying into the face of the Portland Formation. By 1767, East Middletown had separated from its west-bank origins and renamed itself Chatham. Sometime between 1768 and 1774, Thomas Johnson III moved to the east side of the Connecticut River and bought out the Stancliff brothers’ stone-cutting shop. He cut stone on an inherited southern parcel of the quarry, and his brothers worked another shared parcel. By 1782 Thomas had bought out his brothers’ interest and had also acquired the Stancliff brothers’ six-acre parcel of quarry land, previously owned by their father. The Johnsons, with the participation of the Stancliff brothers, continued to develop the quarry and expand their business, removing the massive blocks from their bedding, then cutting and dressing pieces for use as gravestones, foundations, and lintels.

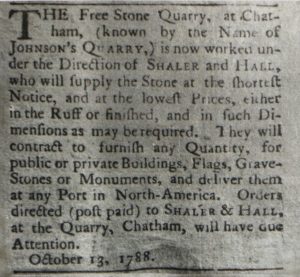

Advertisement (newspaper unknown) for the Shaler and Hall Quarry, Portland, October 13, 1788. Courtesy of John A. Pawlowksi

In 1788, Johnson was bought out by Nathan Shaler and Joel Hall, who purchased his quarry lands for little more than $3,000. Shaler and Hall developed the first large-scale commercial quarry operation on the site.

By 1818, Shaler and Hall had increased the value of their investment nearly fifteen-fold, specializing in the removal of stone from the quarry and leaving to others its formation into a finished product. The age of individual artistry gave way, and soon a series of quarries operated by other partnered owners lay shoulder to shoulder along the river. The Portland Formation rang with the sounds of tools and machines set in motion first by the demands of these commercial partnerships and later by the stockholders and boards of directors of corporations. Shaler and Hall, Hurlburt and Roberts, Patten and Russell, the Brainerd Brothers, and other partners exercised their social, political, and financial influences extensively, selling Portland brownstone well past state boundaries. By 1841, the western portion of Chatham had separated from the rest of the town and renamed itself Portland after the quarry town in England, and “Portland Brownstone” was being shipped to meet the needs of builders from Boston to San Francisco.

The towns of Middletown and Chatham had, meanwhile, retained a portion of the Portland Formation for town use. Recognizing this notable natural resource as a marketable commodity, several prominent Middletown citizens developed a plan to entice an institution of higher learning to put down roots in their city—roots built of Portland Brownstone. They built two buildings on High Street to establish a campus and offered the net profits and rents of the town quarry for 40 years in exchange for establishing a college on the site. They wooed the Episcopal founders of Washington College (renamed Trinity College in 1845) but the diocese turned down the offer (although they did later buy stone for the school’s campus in Hartford). For a short while, a military academy occupied the buildings, but it moved on in 1829, and the campus was abandoned. In 1831, the Methodist Church bought the vacant campus and formed Wesleyan University. From 1833 to 1884, many of the university buildings still in use today were constructed of or trimmed in brownstone.

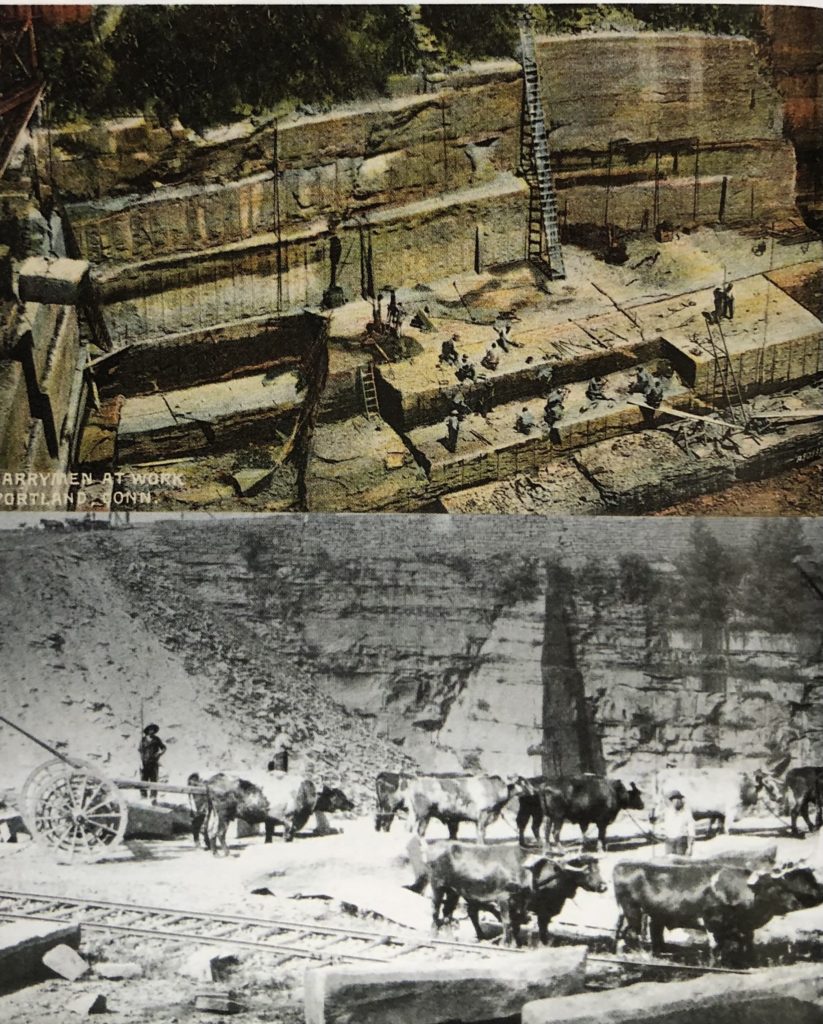

top: postcard, “Quarrymen at Work, Portland, Conn.”, early 1900s. Courtesy of Peggy B. and George P. Perazzo, Stone Quarries and Beyond. bottom: Connecticut Historical Society

Working the Quarry

While Wesleyan rose on the western hills, on the eastern side men toiled from dawn till dark, six days a week. Following a notable loss of a ready labor force due to westward expansion, many men of Irish descent were recruited from beyond state lines to build Connecticut’s canals and railroads and to work in its factories, mines, and quarries. By the 1830s and through the 1850s—the height of the famine years in Ireland—some may even have been hired right at the point of entry in New York City. According to David Dudley Field’sCentennial Address With Historical Sketches of Cromwell, Portland, Chatham, Middle-Haddam, and Middletown, and its Parishes (William B. Casey, 1853), 900 men were working the quarries by 1850. That number rose to 1,200 in 1852, with another 200 hired just to move earth that would expose more stone. Soon the quarries covered 100 acres. The contiguous operations extended a half-mile along the river and sank to depths of up to 200 feet below the surface—even deeper than the adjacent riverbed. During the quarries’ heyday from 1850 to 1890, varied sources report that as many as 1,500 men, 150 yoke of oxen, 60 teams of horses, and 40 quarry schooners were involved in the movement of stone.

Work was largely seasonal. Typically, workers were hired for an eight-month season from April through November, though some work went on year-round. The day was highly regimented. The men took up their tools, ate their noon meal, and rested by the bell. Depending on the month, the workday began as early as 6 a.m. The length of the noon break varied by the month as well, stretching to two hours in midsummer, when the workday was longest, and shrinking to an hour in the cooler months. Year-round, the workday ended at sundown, when most workers—nearly all of them Irish and, by the 1870s, Swedish—returned to company-owned houses on quarry land or in town.

The History and Architecture of Portland (Advocate Press, 1980) records that unmarried workers usually had rooms in local boardinghouses; married men with families were housed in company-owned tenements; and skilled workers might live in single-family homes. Many of the Irish workers lived in dense ethnic enclaves in the area known as the Sand Bank. Local businesses and the quarry company store offered credit to workers, and at the end of the eight-month working season, non-salaried workers received a lump-sum payment of their daily or monthly wages, from which was deducted rent, board, and any extended credit. Yearly salaries were paid to the proprietors, timekeepers, agents, and such skilled workers as blacksmiths, surveyors, and stonecutters.

Skilled workers grew more vitally important as methods of quarrying became more sophisticated. At first the work of cutting stone was accomplished by brute force. Foremen known as rock bosses oversaw crews of quarrymen who used picks, shovels, crowbars, sledgehammers, and wedges to loosen the stone; a system of pulleys, chains, and ropes was used for lifting and hoisting. Initially, inclined roadways took men, oxen, and equipment to the floor of the quarry. As the holes deepened, the quarrymen descended and ascended by a system of ladders and platforms attached to the quarry walls. Later, oxen, horses, and wagons were packed into large crates and lowered to the floor by derricks and cranes. In later years blasting with black powder eased the burden of loosening the stone, and by the 1890s the hardest work was accomplished by steam-powered pumps and engines.

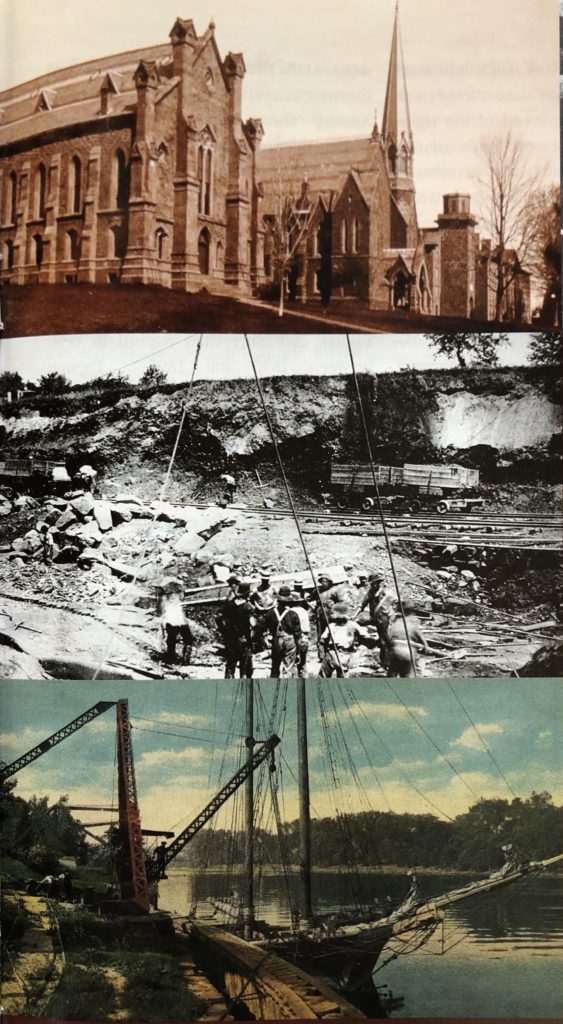

top: “Brownstone Row,” Wesleyan University, c. 1870s. Wesleyan University. Middle: Quarrymen at work. Portland Historical Society. Bottom: postcard, 1911. Quarried stone was loaded onto ships called “brownstoners” docked on the Connecticut River. Courtesy of Peggy B. and George P. Perazzo, Stone Quarries and Beyond

Draft horses and oxen pulled wagonloads of stone to the scrappling grounds, where the material was sorted into waste piles deposited along the riverfront, stored for seasoning, or dressed at Connecticut Steam Brown Stone, the on-site mill built in 1884. In the early days, oxen dragged loaded slings to the docks, but by the 1890s this system was supplanted by steam-powered locomotives and traveling derricks. The Middlesex Quarry Company laid three miles of narrow-gauge track to accommodate its quarry trains, and Brainerd Quarry had the nation’s longest traveler—680 feet—on which they could store and move 800,000 cubic feet of stone. At the riverfront, boom derricks raised the stone to a variety of shallow-draft vessels. Among these were wooden quarry schooners known as brownstoners, built at the Gildersleeve Shipyard just upriver. As long as the Connecticut River was not frozen, these vessels were towed by steamboat to Long Island Sound before sailing on to their final destination.

The use of Portland brownstone in New York, Boston, and other cities reached its peak between 1890 and 1896. Though institutional buildings in New York City more often used New Jersey brownstone, Guinness reports that the 1880 census revealed that of 19,000 New York City buildings that featured stone, 78.6 percent were faced in Portland brownstone, which was especially favored by residential developers (some estimates claimed that nearly 99 percent of housing stock was clad in Portland brown). In fact, the brownstone fronts on the elegant row houses of Boston’s Back Bay, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Manhattan were so uniformly chocolate colored that the term “brownstone” became synonymous with row house, regardless of material, and the term “brownstoner” was applied to the well-to-do residents who generally inhabited them.

By the turn of the 20th century, the use of brownstone as a building material had fallen out of both fashion and favor. Some, like author Edith Wharton, emphatically hated the color. In her 1934 memoir A Backward Glance, Wharton called it “the most hideous stone ever quarried” and lamented that her New York was “hide-bound in its deadly uniformity of mean ugliness.” In truth, its somber hues were the least of brownstone’s possible problems. Some facades were prone to deterioration caused by improper seasoning or wind abrasion. Fractures were common, as was spalling, an exfoliation caused by improper cutting or placement of the stone veneer. Acidic bird droppings could also cause corrosion.

Seeking to accommodate the rising populations of the cities, urban planners created new designs for “vertical neighborhoods,” and engineers developed new technologies and more durable materials. The new curtain-wall skyscrapers developed around the turn of the new century used structural steel and, later, reinforced concrete (which was, oddly enough, commonly called Portland Cement) to support the weight of the building so that exterior walls no longer needed to provide structural support. Brownstone was out, and buildings went, up, up, up. It continued to be used for urban residences but was mostly ornamental: a 4- to 5-inch veneer of façade for a building actually constructed from brick, for instance.

A Quarry Revival

As the popularity of Portland brownstone waned, quarry companies merged and bought each other out. Stockpiled stone sat unused. Connecticut Steam Brown Stone sold out in the early 1930s to the Brazos Brothers, who sold stone only on a limited basis. Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library, completed in 1930, was a rare brownstone project of this era.

Nature did not help the struggling enterprise. In 1936 a spring freshet raised the waters of the Connecticut River to a record 30.21 feet. When the Connecticut leapt its banks in Portland, it filled the quarries in 14 minutes. More than 300 years of industrial history was submerged forever. Eighty thousand dollars’ worth of cranes, saws, track, and locomotive cars was lost. The Brazos Brothers attempted to recover and rebuild, but the quarries were hit again two years later by the Hurricane of 1938. The storm swept northward in New England, splintering houses, derailing trains, and felling 275 million trees in less than a day. But the nadir, for the quarries, was reached with the gales that followed. In the aftermath of pounding rain and 98-mile-per-hour winds, the river whipped to eight-foot whitecaps, roiling from Springfield to Hartford, flooding city streets, ravaging dams, and collapsing bridges as the water rose four inches an hour. Again the quarries became lakes, and this eerily majestic site was inhabited for decades by just ghosts and legends and, on occasion, adventurous teens.

Aerial view of the quarry site, looking south toward Middletown. photo: Shoreline Aerial Photography

More recently, developers have come to the quarry rims from time to time with big ideas, but most disappeared with their plans untapped. Then, beginning in 1999, the Town of Portland, assisted by the Brownstone Quorum, a grass-roots citizens’ movement, acquired a 43-acre parcel along the river. With the assistance and expertise of industrial historians such as Guinness and landscape architect Susan Fiedler, the Quorum and the Town have collaborated on a series of initiatives to preserve and share the legacy of the quarries. In 2000, the U.S. Department of the Interior designated the quarries a National Historic Landmark.

Today the site is under development as a park, with a remarkable outdoor recreation site centered in and around the quarry lakes. Under a lease agreement with the Town of Portland, a partnership of three brothers—Ed, Frank, and Sean Hayes—opened the Brownstone Exploration and Discovery Park in 2007. Now kayakers, scuba divers, hikers—and yes, even teenaged cliff jumpers—can explore the awesome remnants of a bygone age.

Well—not quite bygone. On an upper bench of a nearby cliff face, the sounds of a quarryman can still be heard. Geologist Michael Meehan, owner of Portland Brownstone Quarries, still surveys and measures the ancient rock with a practiced eye. Quarrymen Rick Lane and Chris Markham still cut and trim the blocks with the strength of laborers and the pride of artists. By the square foot, the cubic foot, and by the “tunn,” the stone leaves the quarry by the piece and by the load. Master carver Christoph Henning might fashion a one-of-a-kind decorative design that could be used in such institutional restorations as Charleston’s Saint John the Baptist Cathedral, or a flatbed of raw stone might be hauled to Vermont to be dressed for special residential projects: a doorway, some stair treads, a lintel. Their work, done as much by hand and heart as by machine, ensures that Portland stone, with its signature color, still travels far and wide.

NOTE: Michael Meehan closed Portland Brownstone Quarries in 2012.

Explore!

“Written in Stone: How Connecticut’s Landscape Shapes our Lives,” Summer 2006

“The Industrial Might of Connecticut Pegmatite” Summer 2010

Read more stories about Connecticut’s historic landscape on our TOPICS page.

Brownstone Exploration and Discovery Park is located at 161 Brownstone Avenue, Portland. The park is open year-round. For seasonal hours, activities, and rates call (866) 860-0208 or visit http://brownstonepark.com.