(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

Mystic, Blue Point, Stella Mar, Whale Rock, Sixpenny, Copp’s Island, Thimble Island: these are just a few of the Connecticut-grown oysters you might find in restaurants along the shoreline. Today, succulent Connecticut oysters (designated the Connecticut State Shellfish in 1989) are grown over the course of three to four years on beds or in bags, planted from seed (technically, tiny, fully formed oysters), by oystermen. No two oyster farmers harvest exactly the same way now, and, as it turns out, that has always been the case.

When Connecticut was first settled by Europeans, oysters were so plentiful along the shore that you could actually wade into the water and pull them off the natural beds that formed reefs along the bottom of Long Island Sound, and there was no such thing as oyster farming.

Oysters are bivalve mollusks that reproduce by spawning in summer months. Once the tiny swimming oyster larva begins to develop a shell, the weight causes the animal to sink. These young oysters, called spat, adhere to the bottom, cementing themselves on top of previous generations and quadrupling in size during their first few weeks of life. They remain, stuck there, until they are harvested, are consumed by a marine predator, or die of natural causes.

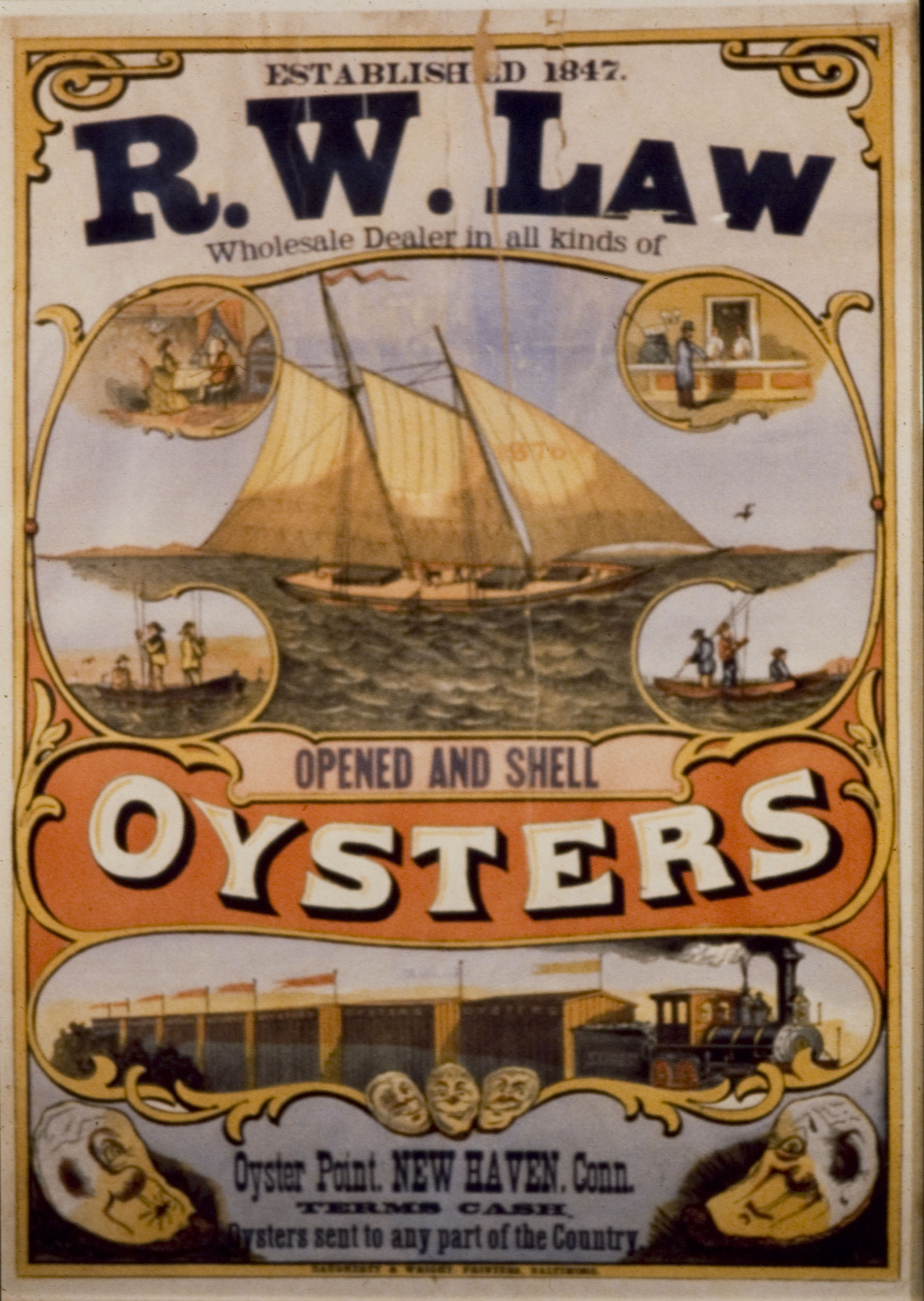

A result of collecting large numbers of oysters so close to shore, by hand or with rakes fabricated by local blacksmiths, was that by the end of the 18th century, oyster fishermen had to make their way farther from land to find oysters. Using long wood-handled tongs, oystermen would gather piles of oysters and shells and cull out the live oysters, returning the empty shells to the bottom so subsequent young oysters had a hard surface to attach to. While tonging for oysters could be done from any small boat, builders in New Haven, Fair Haven, and Guilford perfected well-balanced, long skiffs called “sharpies” that could bring loads of oysters to shore. These shallow-draft boats were so well designed that they were much copied along the entire east coast.

Oyster tongs, 19th century, on display at the New Haven Museum. Long handles called stales would have been attached, allowing an oysterman to scoop oysters off the sea bottom as far as 15 feet below while standing in his boat. photo: Mary Donohue, collection of Mystic Seaport

Once all of the oysters have been harvested from an area none will return unless put there purposefully, so oystermen continued to move farther from shore. Fishing dredges, which had been invented in Europe in the 14th century, were repurposed for oyster harvesting in Long Island Sound. Peter Decker, a Norwalk oysterman, in 1874 introduced the steam-powered dredger, which increased the rate of harvest from about 25 bushels per day by sail to 20 times that much. Not only did these iron mesh contraptions dramatically increase the number of harvested oysters, they also had environmental consequences for the sea floor because they disrupted the habitat for other organisms and stirred up sediment that could choke remaining oysters.

The threat of over-fishing was recognized early. By the middle of the 18th century, the Connecticut General Assembly passed laws that allowed shoreline towns to control oyster fishing. In 1762 the city of New Haven passed a local law making it illegal to take oysters in the summer months when they would be reproducing, and in 1766 dredging was prohibited. The adage that you should only eat oysters in months whose names contain an “r” arose not because, as it came to be believed, there was no refrigeration to keep oysters safe to eat in those summer months. The informal rule actually stemmed from the need to allow oysters opportunity to spawn during the summer—and the fact that oysters change in texture when they reproduce and thus were (and still are) less appealing to eat. (Later, statutes were enforced as a way to limit the transfer of bacterial or viral illness as well.)

Laws passed in 1855, as noted in the Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries dated 1873 – 1875, established regulations for oyster plantations. They could not be larger than two acres and must be in waters where the cultivation would not inhibit navigation. The regulations defined the difference between public and private beds. However, friends, family, even paid strangers could purchase two-acre beds within the same geographic area, which often led to one person’s managing large underwater tracts of land. In addition, landowners were allowed to place dams on coastal creeks, blocking the currents from carrying oyster spawn out of what would become oyster ponds. As long as no one complained, the pond was yours.

Legislation alone was not enough to keep the Connecticut oyster industry going. Oystermen had to be proactive. They began purchasing “seed” oysters from the Chesapeake Bay. With luck, these seeds would eventually grow to harvest size and in the meantime reproduce for a couple of seasons.

The Commissioner of Fisheries report in 1887 mentions the first methods used in the United States for collecting oyster spawn and growing oysters from spat. In the Poquonnock River in Groton, enterprising fishermen stuck white birch bushes in the mud at the bottom of the river to catch the oyster larvae as they formed into spat. Over time, fishermen extended the area in which they were “planting” these shrubs, which were said to yield as many as 1,000 bushels of oysters per acre.

Despite the success these oystermen had, collecting spat so carefully was not something most fishermen did. Most simply planted mature oysters on a cultch-covered area (cultch, the substrate that oysters grow on, would be collected in the form of oyster shell from culling houses and laid down on the sea floor) and allowed them to spawn there with the spat falling on these man-made beds. The young oysters would then be collected and moved to other beds to finish growing to market size. They were moved so that the mature oysters could be left to reproduce year after year. Moving the young oysters also made it easier to harvest them later.

Oystermen faced other challenges besides overfishing. Raw sewage was routinely routed into Long Island Sound. Industrialization led to pollution by other substances, including heavy metals. As filter feeders, oysters take in pollutants and bacteria, which can then be passed on to people who consume the shellfish.

In the 1890s a clear link between oysters and typhoid fever was established, and in 1892 when members of three Wesleyan University fraternities became infected with typhoid, investigation showed that all 29 cases involved young men who had consumed oysters “fattened” at the mouth of the Quinnipiac River, not far from a sewage outlet from a house with two known cases of typhoid fever. The typhoid epidemic in the eastern United States during the winter of 1924 – 1925, which killed 150 people and was also blamed on oysters, received so much press that it had a drastic effect on the oyster industry.

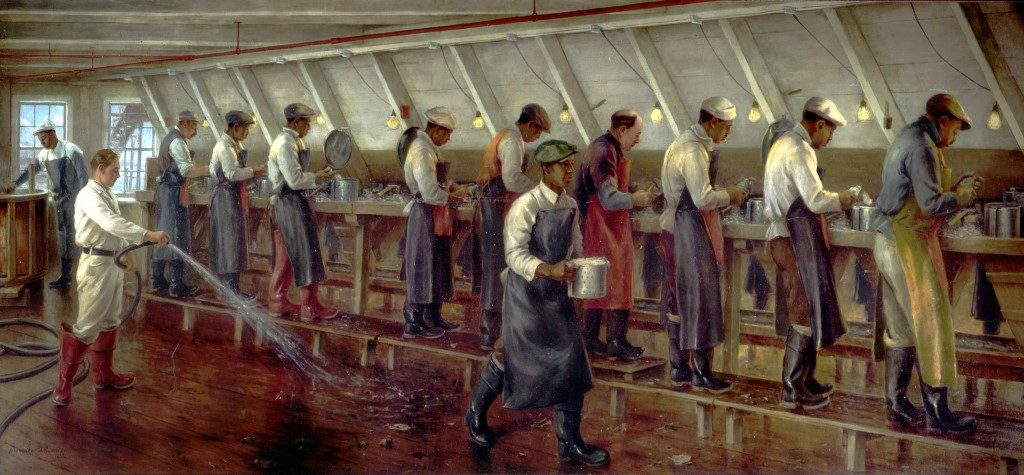

Alexander Rummler, “Shucking oysters,” c. 1930s. Works Progress Administration mural painted for the Norwalk High School cafeteria. Owned by the City of Norwalk; on view at the Maritime Acquarium, Norwalk

Natural events also took their toll. Hurricanes in the 1930s and 1950s further decimated the oyster industry. Finally, oyster predation, such as that from the starfish boom of 1957, negated any resurgence the oysters might have had.

The Connecticut Clean Water Act, passed in 1967, began a reversal of fortunes for Connecticut’s oyster industry. In the late 1970s the state and commercial growers began laying clean oyster shell on natural oyster beds in Connecticut waters in hopes of reviving the oyster populations in Long Island Sound, estuaries, and rivers. Meanwhile, in Milford, the Milford Lab, established in 1931 as part of the National Marine Fisheries Service, which had done extensive research into mechanical and chemical means of controlling predation by starfish and small snails called oyster drills, was working on aquaculture techniques. The lab had been growing a variety of single-cell algae types in the hopes of finding those that best matched the needs of oyster spat. They were so successful that the strategy of growing algae for feeding oysters and cultivating the oysters themselves became known as the “Milford Method” and was used all over the world. Seed oysters could be harvested from natural beds or grown in hatcheries using the techniques developed in Milford. These small oysters would be transplanted to the beds laid by the commercial oystermen.

With these strategies in place, there was once again a resurgence of oyster harvesting. But population growth and other, shifting ecological concerns posed other difficulties. In the late 1990s, with uncharacteristically high temperatures in Long Island Sound, two marine parasitic diseases took their toll. Dermo, a disease caused by a slow-acting parasite, and MSX, another parasite, one with faster effects, struck Long Island Sound after wreaking havoc all along the Atlantic coast. The oysters that survived MSX would be resistant, but they accounted for only about five percent of the original population. However, because dermo infections allow an oyster to grow for up to three years after it is first infected, natural seed oysters spawned from diseased parents might carry the parasite, too. Adding these young oysters to beds would simply perpetuate the disease. On the other hand, oysters grown in hatcheries would be free from disease.

Since the mid-2000s oystering in Connecticut has experienced another renaissance. Commercial oyster farmers can lease inshore beds from their local towns or offshore beds from the state, depending on how substantial their operation is. Recreational shell fishermen can apply for a permit to harvest a relatively small number of oysters from town-designated beds. Some growers, like Norm Bloom in Norwalk, employ a traditional method in which shell is laid down on leased beds after oysters have spawned, but before spatfall. Once these young oysters have fallen to the sea floor and grown to seed size they are dredged up and moved to another grow-out bed, where they are harvested once they reach the legal size of three inches.

Other oystermen rely on oyster seed grown in hatcheries. The Noank Aquaculture Cooperative, which operates at the mouth of the Mystic River, runs a hatchery in Southold, Long Island. There, the life cycle of the oysters is controlled by regulating temperature and the particular cocktail of algae (grown there in tanks) they are fed. Broodstock oysters spawn in their own tanks, and the eggs and sperm are collected and added to a different tank for fertilization. The larvae that develop a day later consume a different mix of algae until spatfall. The tiny oysters are moved to another tank that filters in seawater with a natural plankton supply that feeds the oysters until they are large enough (about an eighth of an inch) to be sold as seed.

After that, every oyster farmer seems to do something different. Some plant the tiny seed directly on the bottom of protected areas. Others use large plastic mesh bags, moving the oysters to new bags with larger mesh as they grow. Some oystermen grow the oysters entirely in bags that get moved to a puration site, a designated area that is free of toxins and bacteria, before they are sold. Others, such as Charles Island Oyster Farm in Milford, grow the oysters in cages until they are large enough to plant on beds with less risk of predation. Then they are planted on the beds managed by the farm. In Branford, the Thimble Island oyster is grown in cages along with clams, mussels, scallops, and kelp in what owner Bren Smith describes on his website and in a 2013 TEDx talk as 3D ocean farming. This array of methods, along with ongoing research into breeding resistant brood stock, is helping to ensure that Connecticut oysters are here to stay.

The next time you visit your local restaurant for its “buck a shuck” special, you can feel good about supporting the local Connecticut economy, stave off a cold (oysters are one of the richest sources of zinc, which may help protect against such illnesses), and simply enjoy some delicious fresh seafood.

Rachel Thomas-Shapiro is the Working Waterfront Supervisor at Mystic Seaport. She is a scientist and historian with a particular interest in local fisheries and sustainability. She is also quite fond of oysters.

Explore!

“Native American Oystering,” Summer 2017

Read all of our stories about Food & Drink on our TOPICS page