By Eric Lehman

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1838 Louis Daguerre created the first photograph of a human being. Samuel Morse first demonstrated the telegraph. Railroads were booming across the United States, mass production of newspapers had just be come possible, and the first steamship purposely built to cross the Atlantic Ocean had just sailed. Since these inventions and developments would make modern celebrity possible, it makes perfect sense that America’s first international star—Charles Stratton, a.k.a General Tom Thumb—was born that same year.

come possible, and the first steamship purposely built to cross the Atlantic Ocean had just sailed. Since these inventions and developments would make modern celebrity possible, it makes perfect sense that America’s first international star—Charles Stratton, a.k.a General Tom Thumb—was born that same year.

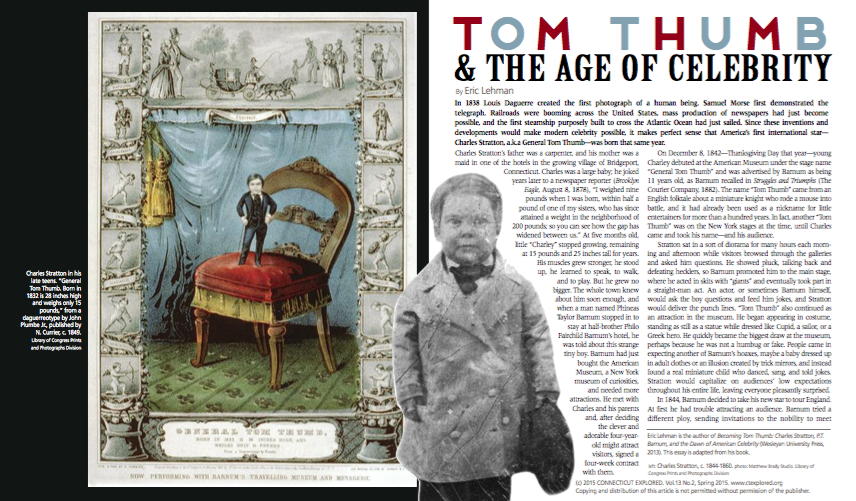

Charles Stratton’s father was a carpenter, and his mother was a maid in one of the hotels in the growing village of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Charles was a large baby; he joked years later to a newspaper reporter (Brooklyn Eagle, August 8, 1878), “I weighed nine pounds when I was born, within half a pound of one of my sisters, who has since attained a weight in the neighborhood of 200 pounds; so you can see how the gap has widened between us.” At five months old, little “Charley” stopped growing, remaining at 15 pounds and 25 inches tall for years. His muscles grew stronger, he stood up, he learned to speak, to walk, and to play. But he grew no bigger. The whole town knew about him soon enough, and when a man named Phineas Taylor Barnum stopped in to stay at half-brother Philo Fairchild Barnum’s hotel, he was told about this strange tiny boy. Barnum had just bought the American Museum, a New York museum of curiosities, and needed more attractions. He met with Charles and his parents and, after deciding the clever and adorable four-year-old might attract visitors, signed a four-week contract with them.

On December 8, 1842—Thanksgiving Day that year—young Charley debuted at the American Museum under the stage name “General Tom Thumb” and was advertised by Barnum as being 11 years old, as Barnum recalled in Struggles and Triumphs (The Courier Company, 1882). The name “Tom Thumb” came from an English folktale about a miniature knight who rode a mouse into battle, and it had already been used as a nickname for little entertainers for more than a hundred years. In fact, another “Tom Thumb” was on the New York stages at the time, until Charles came and took his name and his audience.

He sat in a sort of diorama for many hours each morning and afternoon while visitors browsed through the galleries and asked him questions. He showed pluck, talking back and defeating hecklers, so Barnum promoted him to the main stage, where he acted in skits with “giants” and eventually took part in a straight-man act. An actor, or sometimes Barnum himself, would ask the boy questions and feed him jokes, and Stratton would deliver the punch line. “Tom Thumb” also continued as an attraction in the museum. He began appearing in costume, standing as still as a statue while dressed like Cupid, a sailor, or a Greek hero. He quickly became the biggest draw at the museum, perhaps because he was not a humbug or fake. People came in expecting another of Barnum’s hoaxes, maybe a baby dressed up in adult clothes or trick mirrors, and instead found a real miniature child who danced, sang, and told jokes. Stratton would capitalize on audiences’ low expectations throughout his entire life, leaving everyone pleasantly surprised.

In 1844, Barnum decided to take his new star to tour England. At first he had trouble attracting an audience. Barnum tried a different ploy, sending invitations to the nobility to meet General Tom Thumb at a rented townhouse. The Baroness Charlotte de Rothschild took the bait, and the rest of London followed, including Queen Victoria, who invited the duo to Buckingham Palace for an evening entertainment. Stratton performed a Napoleon imitation, and sang “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Then, as he and Barnum backed out of the big picture gallery, the Queen’s spaniel attacked, barking. Stratton swung his tiny cane around as if to fend off the dog in a moment of completely unrehearsed comedy. Victoria invited Stratton again and again to the palace, where he met world leaders such as King Leopold of Belgium and Tsar Nicholas of Russia.

Stratton’s portrayal of Napoleon became legendary, especially after the Duke of Wellington encountered this much smaller version of the opponent he had defeated 30 years earlier. Stratton would play the French dictator for the next 40 years in what became the joke of the century, connecting the idea of smallness with Napoleon so completely that Sigmund Freud possibly based his famous “Napoleon complex” on this strange impression rather than on the real, average-sized French general.

Stratton’s portrayal of Napoleon became legendary, especially after the Duke of Wellington encountered this much smaller version of the opponent he had defeated 30 years earlier. Stratton would play the French dictator for the next 40 years in what became the joke of the century, connecting the idea of smallness with Napoleon so completely that Sigmund Freud possibly based his famous “Napoleon complex” on this strange impression rather than on the real, average-sized French general.

As Stratton developed as a child actor, his main character became himself, though of course still under the name of Tom Thumb. He developed a dry wit, never laughing at his own jokes, with only a small “knowing” smile on his face. He also began to act in short plays rather than skits, and his memorization of hundreds of lines, sometimes for two plays a day, was a remarkable feat in itself for a child. At the same time tutors taught him several languages, various musical instruments, and other subjects such as math and history.

He traveled through France while Barnum rode ahead to set up the engagements. Near the border of Spain, he took a side trip to Pamplona to meet Queen Isabella and watched a bullfight. During these travels he and Barnum became closer and closer, but at the same time Stratton’s parents fought with Barnum in that classic entourage conflict over the love and allegiance of a star. By 1845 his parents were sharing half the profit, but they would have been lost in Europe without Barnum, and they knew it. The relationship was tense. Sherwood Stratton began drinking too much, a habit that would eventually lead him to an early death in the Hartford Lunatic Asylum in 1855.

Returning to America in February 1847, General Tom Thumb was hailed far and wide as “the biggest attraction in town or country.” Newspapers reported on his activities. His newly-rich parents built a large house at the north end of Bridgeport, complete with Charles-sized rooms and furniture. On April 13 young Stratton met President James K. Polk and then toured the eastern United States, Cuba, and Canada. Though he was not yet 10 years old, he had acquired bad habits in Europe, including smoking cigars and drinking wine. He also interacted primarily with adults, never becoming friends with other children, except perhaps Barnum’s older daughters. This loss of childhood haunted him to the end of his life: it was the sacrifice he made for money, fame, and a creative outlet.

Over the next couple decades Charles toured America more than two dozen times. A fan and acquaintance of Barnum, James White Nichols, described one of these shows in his diary. In a packed room at the Danbury City Hall in September 1848, he recorded, people clapped and shouted with glee as Stratton appeared as Frederick the Great of Prussia, complete with the “tottering gait” of an old man. Nichols called Stratton’s singing voice “unearthly” and noted the crowds of female admirers lining up to buy souvenirs, adding that each also received a kiss. Later Barnum and Stratton visited Nichols’s house, and the family took great delight in the friendly repartee between them. Nichols said that seeing the small boy in such a setting was “really worth as much if not more than to see him perform his different feats on the stage.”

In the 1850s, between tours of the United States, Stratton appeared often on the New York stage, acting in plays such as The Forty Thieves and The Miserable Husband. He was a teenager now, and he tried to stretch his acting skills. He got his best chance in 1856 as “Tom Tit” in an adaptation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Dred. He provided the comic relief in what otherwise was a serious play about the suffering and education of slaves. It would be his last appearance as a thespian. In his 20s he appeared less frequently in full-company productions, reverting instead to stand-up and sketch comedy. Perhaps he had reached his limit as an actor; after all, at less than three feet tall he could not play King Lear.

In 1856, Barnum lost his fortune after investing in a failing clock company. Charles volunteered his services to help his former manager, telling him, “Put me into any ‘heavy’ work, if you like. Perhaps I cannot lift as much as some other folks, but just take your pencil in hand and you will see I can draw a tremendous load.” Barnum accepted the offer, and the pair returned to Europe for another successful tour of England, France, and Germany. By 1859, Barnum had enough money to pay his creditors and recover both his museum in New York and his mansion in Bridgeport.

In 1856, Barnum lost his fortune after investing in a failing clock company. Charles volunteered his services to help his former manager, telling him, “Put me into any ‘heavy’ work, if you like. Perhaps I cannot lift as much as some other folks, but just take your pencil in hand and you will see I can draw a tremendous load.” Barnum accepted the offer, and the pair returned to Europe for another successful tour of England, France, and Germany. By 1859, Barnum had enough money to pay his creditors and recover both his museum in New York and his mansion in Bridgeport.

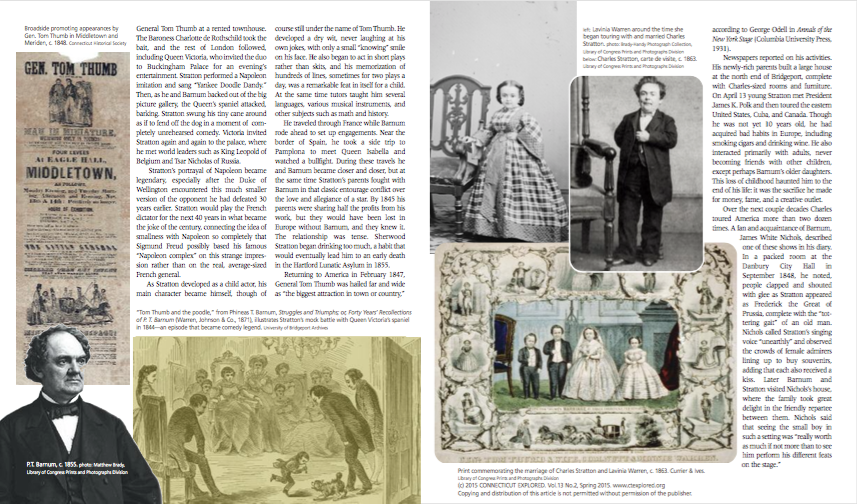

While America tore itself apart during the Civil War, Stratton fell in love. A small woman from Middleboro, Massachusetts named Lavinia Warren Bump had caused a minor sensation in the entertainment world with her sad songs and perfect features. Barnum offered her a contract, and she and Stratton, who had returned from his European tour in 1859, spent time together beginning in 1862. According to Barnum in Struggles and Triumphs, Charles brought her to Bridgeport and, after introducing her to his mother and gaining her approval, asked her to marry him. Warren’s mother agreed to the match, on the condition that the 25-year-old Stratton shave off his new mustache. He was willing to make the sacrifice.

Their wedding at Grace Church in New York City became the most talked about event of 1863, save perhaps the Battle of Gettysburg. Thousands of people jammed the streets of Manhattan, and police had to cordon off several blocks. The best man was the unusually small “Commodore” George Nutt, one of Barnum’s latest hires, and the maid of honor was Minnie Warren, Lavinia’s younger and astonishingly smaller sister. (Both the Bump sisters dropped that surname when establishing their public personas.) The four of them became immediately inseparable in the public’s mind.

After the wedding Charles and Lavinia took a train to the White House. Abraham Lincoln maintained a fine line between his amusement and his respect for even these littlest of citizens. “God likes to do funny things,” the lanky 6-foot-4-inch president told his son at the party in the East Room of the White House. “Here you have the long and short of it.” The next day the newlyweds crossed the Potomac to Arlington Heights to visit Union soldiers encamped there. They were greeted with “cheers, throwing up of caps, and shouts from all sides,” recalled Lavinia in her Autobiography of Mrs. Tom Thumb (Archon Books, 1979).

The new foursome of little people toured Canada and the borderlands along the Mississippi as a sort of USO show before Charles and Lavinia took a real honeymoon to England, leaving on October 29, 1864. They inexplicably agreed to participate in one of Barnum’s worst humbugs of all time: they announced they’d had a child, despite the fact that Lavinia had spent the months leading up to the supposed birth touring with no sign of pregnancy. Furthermore, the enormous child they showed off could not possibly have come from her tiny body, and the family all knew that it was her nephew Gus. But, strangely, no one, including Queen Victoria, questioned this. Perhaps that was because Stratton had never before taken part in this sort of show-business hoax.

Gus quickly outgrew the part, as did the next “baby.” Then, as was recently discovered and reported in the BBC documentary The Real Tom Thumb: History’s Smallest Superstar (2014), a tragedy occurred in September 1866 when the baby then playing their child died. They buried her as Minie Warren Stratton, at a ceremony attended by a thousand people. The mystery remains as to who the baby was. Was it a foundling they had picked up from an orphanage? The baby’s gravestone in Norfolk, England is a dark reminder that humbugs can go wrong, and that celebrity can be a monster that feeds on the truth.

In May 1869, Barnum wrote to the Strattons to suggest a tour around the world, starting out in the U.S. on the newly completed Pacific Railroad. The General Tom Thumb Troupe—which included Minnie and George Nutt—became the first group of performers to use that railroad to cross the continent. In San Francisco the troupe boarded the steamer America for Japan. After meeting Emperor Meiji, their next stops were Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore. In India they rode on elephants to visit the King of Benares.

After performing in Ceylon, India they sailed to Australia, despite Stratton’s concern about “convicts.” In Sydney they met Prince Alfred, who flirted with Minnie at a costume ball—yet another of the dozens of royal figures who paid homage to the “General” and his troupe. They saw the pyramids of Egypt, Italy, Austria, and England yet again, returning to New York almost three years to the day from the day they left. The General Tom Thumb Troupe had become the first American celebrities to circumnavigate the globe.

In 1871 the Strattons moved to Middleboro, Massachusetts to be near to Lavinia’s family, though Charles still traveled often to Bridgeport and New York. His leisure activities began to take more of his time, especially during the off-season. He spent time with his fellow Freemasons, hunted for deer with a specially made rifle, and sailed his yachts on Long Island Sound. He joined the Brooklyn Yacht Club, the only real yachting association in the country at that time, and took part in races from New York to Nantucket, often winning or coming in second. Coverage of his activities briefly moved from the entertainment section of the newspaper to the sports pages.

Tragedy entered their lives when Lavinia’s sister Minnie died in childbirth in 1778 and their former colleague George Nutt destroyed himself with alcohol in 1881. (Nutt was kicked out of the troupe in 1774, and his replacement Edward Newell married Minnie.) Stratton was having his own troubles. Having eaten too much rich food, he’d grown to 75 pounds and an “enormous” 40 inches tall. And then, at the Newhall House in Wisconsin on January 10, 1883, he and Lavinia were caught in one of the largest hotel fires in history. Their manager’s wife and their coachman died, and the experience shook Stratton to the core. He never recovered, and six months later he died of a stroke in his Middleboro home.

“General Tom Thumb was probably better known than any man in the United States,” the Los Angeles Herald noted in his obituary on July 21, 1883. He had performed in front of millions of people, toured the world, and become America’s first international celebrity. But in the decades after Stratton’s death, the reputation and fortunes of little people declined, so that by the early 20th century they experienced profound prejudice. The recent theories of social Darwinists and old superstitious fears of “dwarfs” combined in a terrible way, and little people were shunned. High culture and low culture split completely, and though Barnum had mixed the two without compunction, he and his world became “low culture.” By the 1930s when Charles Burpee wrote his seminal history of Connecticut, “Tom Thumb” barely earned a footnote.

It’s time for that to change, for us to include Charles Stratton in the history in which he played a vital role. This native of Connecticut was one of the most remarkable figures of the 19th century, America’s first performer to achieve widespread national and international fame, a man and a legend in one small body.

Eric Lehman is the author of Becoming Tom Thumb: Charles Stratton, P.T. Barnum, and the Dawn of American Celebrity (Wesleyan University Press, 2013). This essay is adapted from his book.

Explore!

Read more stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.

The Barnum Museum, 820 Main Street, Bridgeport

Items related to Tom Thumb and his troupe members, including miniature carriages, a gilded canopy bed presented in 1844 to Charles Stratton while he was on tour in England, and an English portrait of Stratton at six years old, are on view. (Items of clothing are on view for limited periods due to preservation requirements.) Open Thursday and Friday, 11 a.m. – 3 p.m., and at other times concurrent with programs. 203-331-1104, barnum-museum.org

Podcast!

Hear an hour-long interview with Eric Lehman by Marian Pierre-Louis of Fieldstone Common HERE or fieldstonecommon.com/becoming-tom-thumb-eric-lehman/.