By Jerry Roberts

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2012

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

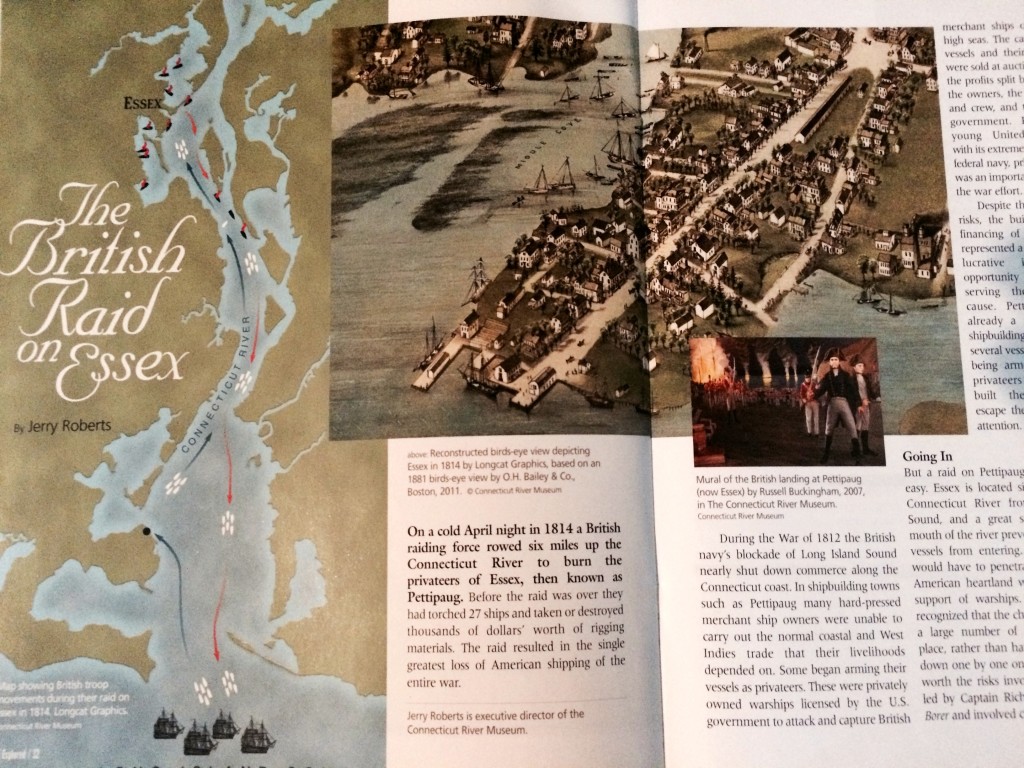

On a cold April night in 1814 a British raiding force rowed six miles up the Connecticut River to burn the privateers of Essex, then known as Pettipaug. Before the raid was over they had torched 27 ships and taken or destroyed thousands of dollars’ worth of rigging materials. The raid resulted in the single greatest loss of American shipping of the entire war.

During the War of 1812 the British navy’s blockade of Long Island Sound nearly shut down commerce along the Connecticut coast. In shipbuilding towns such as Pettipaug many hard-pressed merchant ship owners were unable to carry out the normal coastal and West Indies trade that their livelihoods depended on. Some began arming their vessels as privateers. These where privately owned warships meant to attack and capture British merchant ships on the high seas. The captured vessels and their cargos were sold at auction and the profits split between the owners, the captain and crew, and the U.S. government. For the young United States with its extremely limited federal navy, privateering was an important part of the war effort.

Despite the obvious risks, the building and financing of privateers represented a potentially lucrative investment opportunity while also serving the national cause. Pettipaug was already a well-known shipbuilding center. That several vessels were now being armed and new privateers were being built there did not escape the Royal Navy’s attention.

Going In

But a raid on Pettipaug would not be easy. Essex is located six miles up the Connecticut River from Long Island Sound and a great sand bar at the mouth of the river prevented large naval vessels from entering. A raiding force would have to penetrate deep into the American heartland without the direct support of warships. Still, the British recognized that the chance of destroying a large number of privateers in one place, rather than having to hunt them down one by one on the high seas, was worth the risks involved. The raid was led by Captain Richard Coote of HMS Borer and involved crews mustered from four British warships of the squadron blockading New London and the Sound. They anchored off the mouth of the Connecticut River on the evening of April 7 and dispatched 136 sailors and marines in six heavily armed ships’ boats.

Their first task was to secure the fort at Saybrook, which dominated the mouth of the river, so the raiding force would not be trapped on the way out. Unbelievably, two years into the war, the British found the fort without a garrison, guns, or ammunition. They continued to row upstream against wind and tide, arriving on the Pettipaug waterfront at 3:30 the next morning.

According to Coote’s report to the Admiralty, “We found the town alarmed, the militia all on alert, and apparently disposed to oppose our landing with one four pound gun.” But the British had come with overwhelming force, their boats undoubtedly armed with swivel guns and carronades. “After the discharge of the boat’s guns and a volley of musketry from our marines,” Coote continued, “they prudently ceased firing.”

No one in the sleepy village had expected the war would be brought so far inland. But here it was. According to a report published in the Connecticut Gazette a few days after the raid the British made a simple ultimatum to the town’s people gathered there in the wee hours. “Captain Coote informed them that he was in sufficient force to affect the object of his expedition, which was to burn the vessels; and that if his party were not fired upon, no harm should fall upon the inhabitants, or the property unconnected with the vessels…” In other words, the message was, stay out of our way and you can keep your town. The good people of Pettipaug looked at the marines, did the math, and withdrew. Quietly, riders were sent out into the night to seek military assistance from New London and surrounding communities.

As British marines secured the town, sailors set to burning ships and removing naval stores from waterfront chandleries and warehouses. They also took the town’s considerable stocks of West Indies rum, an important commodity in an age when soldiers and sailors on both sides were issued half a pint of rum a day as part of their compensation.

As the harbor blazed throughout the night, several heroic but futile attempts were made to save individual ships by towing them out of sight or extinguishing flames with buckets of water. Despite these efforts, however, by 10 the next morning the British had torched 25 vessels, keeping meticulous records of the names, tonnage, rigs, and potential armaments of each, from the 400-ton ship Osage to 25-ton coastal sloops. They loaded the stolen chandlery supplies and rum into two captured privateers, the brig Young Anaconda and the schooner Eagle. With militia from neighboring towns beginning to reach the area, it was time for Captain Coote and his men to make their escape.

Getting Out

As the British towed the two captured ships down river against the wind on a falling tide, the Young Anaconda went aground a mile south of the town. Its cargo was transferred to the schooner, and the brig was torched. Despite being exposed to sporadic musket fire from shore, Coote decided that proceeding through the narrower stretch of river farther downstream in broad daylight posed a greater risk than waiting for the cover of darkness. He anchored the schooner and his boats and waited for nightfall.

At this point, Major Marshe Ely, commanding the growing American militia forces from Lyme and Saybrook, sent a small boat under a flag of truce to deliver a message to the British. Ely was confident he now had Coote at his mercy. “Sir, To avoid the effusion of human blood is the desire of every honorable man. The number of forces under my command are increased so much as to render it impossible for you to escape. I therefore suggest to you the propriety of surrendering your selves prisoners of War and by that means prevent the consequence of an unequal conflict which must otherwise ensue.”

Coote disagreed with Ely’s assessment. In his report to the Admiralty he wrote with typically British understatement, “My reply was verbal, assuring the bearer, that tho’ sensible of their humane intentions, we set their power to detain us at defiance.”

At sunset the British transferred the stolen supplies and rum to the boats, set fire to the schooner, muffled their oars, and began slipping downstream under cover of darkness. U.S. marines dispatched by Stephan Decatur from New London had begun to arrive, along with federal troops and additional militia and volunteers. Several artillery pieces were quickly set up on both sides of the river. The British came under increasing musket and cannon fire from both banks. Two British marines were killed as the boats ran the gauntlet, now illuminated by bonfires and picket boats with torches. The musket and cannon fire from the narrows (today spanned by the I-95 Baldwin Bridge) was intense. Coote reported, “I believe no boat escaped without receiving more or less shot.” Yet the black of night and the swift outbound current enabled the British to drift silently past the fort at Saybrook, drawing only ineffectual parting shots from the defenders now gathered there.

By 10 p.m. the raiding party had reached the safety of the British warships. For the loss of only two men killed and two seriously injured the British had torched more than two dozen American ships and taken or destroyed thousands of dollars’ worth of supplies and equipment—not to mention all that rum. It was perhaps one of the most successful small boat raids in history.

The British raid devastated the local economy and nearly ruined the handful of old shipbuilding families who owned most of the vessels that had been destroyed. The prevailing local attitude was that the disaster had resulted from the federal government’s total neglect of its duty to protect this important shipbuilding community. This was made clear in a letter from the selectmen of Saybrook (which at the time included Pettipaug) to Connecticut Governor John Cotton Smith. “Your Excellency must be sensible that the Inhabitants of this Town feel Indignant at the General Government for declaring a war of offence & then leaving…the Mouth of the Connecticut River unprotected… under the guns of a large squadron of the enemy.”

Four months later the British bombarded Stonington. Unlike the strategic raid on Pettipaug, the attack on Stonington was a punitive bombardment of an extremely exposed, and as it turned out tenaciously brave, coastal town. Two weeks after that, on August 24, the British burned the nation’s capital. The raid on Pettipaug had been eclipsed, and the town did its best to forget this dark chapter in its history. Within two years it had changed its name to Essex, and the raid passed into obscurity and folklore.

Jerry Roberts was executive director of the Connecticut River Museum.

Explore!

“New Discoveries at Battle Site Essex,” Summer 2014

In 1980 a chance meeting between a retired naval officer from Essex and his Canadian counterpart in Halifax brought to light the existence of primary documents associated with the 1814 raid on Essex, including British Captain Richard Coote’s report to the Admiralty. The Essex Historical Society published a pamphlet based on those documents, but the battle was again largely forgotten except for its commemoration in the annual fife and drum parade down Main Street that many locals still refer to as “Losers’ Day Parade.”

In 2008, with the approach of the bicentennial of the War of 1812, the Connecticut River Museum, located on the British landing site in Essex, created a permanent exhibit about the raid; it features artifacts, maps, dioramas, documents, and a 22-foot-long mural of the British landing. In recent years the museum has intensified its on-going research aimed at garnering recognition for this little-known page in our maritime history. Through grants from the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office and support from the National Park Service Battlefield Protection Program official recognition and designation as an 1812 battle site is at last becoming a reality.

In December 2010 a British naval boarding cutlass found in the harbor was donated to the museum, and in June 2011 a ship’s knee, possibly part of one of the American privateers, was found in the river and is currently on display undergoing conservation. Clearly this story is not over; the last chapter has not yet been written!

Visit the Connecticut River Museum’s expanded War of 1812 exhibition, Battle Site Essex, and explore its associated heritage trail throughout the year. The Annual Burning of the Fleet fife and drum parade hosted by Essex’s own Sailing Masters of 1812 and the museum’s commemorative events take place on the second Saturday of May.

Connecticut River Museum

67 Main Street, Essex

860-767-8269; ctrivermuseum.org

Read all of our stories about the War of 1812 in our Summer 2012 issue

Read all of our Maritime history stories on our TOPICS page

Read all of our stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page