by Emma Demar with Elizabeth J. Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2011

Subscribe/By the Issue!

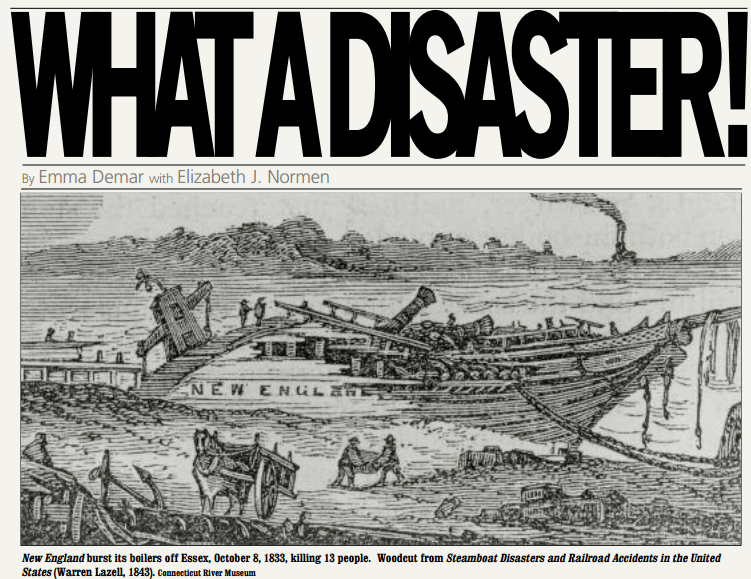

The New England: “The shock was dreadful”

One of the worst steamboat disasters occurred on the dark and stormy night of October 8, 1833 on the Connecticut River. According to Steamboat Disasters and Railroad Accidents (Warren Lazell, 1843 edition), the New England had left New York with about 70 passengers and 20 crewmen on the 7th, destined for Hartford and traveling in the company of Boston, another steamboat. The two boats appeared to be in a race until they parted at the mouth of the Connecticut River at about 1 a.m. Some difficulty occurred with the New England’s engine there, but 30 minutes later, the problem fixed, she continued upriver, arriving off Essex at 3 a.m. The engine was stopped, but as a small boat was lowered to land a passenger, both boilers exploded “with a noise like heavy cannon. The shock was dreadful; and the scene which followed … [w]as awful and heart-rending beyond description.”

The ladies’ cabin suffered the worst effects: “Those who,…on first alarm, sprang from their berths, were more or less scalded. All who were on deck abaft the boilers, were either killed or wounded… .” The heat from the steam was so great that, an unidentified eyewitness reported, one victim’s clothes “were so hot as to scald the hands of those that removed them… . Letters, exposed to the steam, were charred, or reduced to coal in places.”

The captain was in the wheelhouse directing the landing and jumped, or was thrown, to the forward deck, sustaining only bruises. Thirteen people perished, including five crewmen. An unidentified survivor noted that the people of Essex took the survivors into their homes and “every thing which could contribute to their relief and comfort promptly [was]afforded.”

The cause of the disaster was determined to be negligence of the substitute engineer, possibly for letting excessive steam build up during the stop for engine trouble earlier that night.

South Norwalk Train Wreck: “Far Too Many Dead”

By 1853, the era of steamboat transportation had largely given way to trains, but there was still a need to manage drawbridges for safe passage of both modes of transportation.

At 8 a.m. on May 6, 1853, Dr. Gurdon Wadsworth Russell of Hartford and other physicians boarded a train in Manhattan along with 150 other passengers to return home from the annual meeting of the American Medical Association. At 10:15 a.m., Captain Byxbie of the Pacific steamboat whistled for passage through the drawbridge at South Norwalk. As Robert Shaw notes in A History of Railroad Accidents, Safety Precautions and Operating Practices (Vail-Ballou Press, 1978), the bridge was “ordinarily closed to ships, and the [bridge]tender would open it upon their signal only when certain that no trains were approaching.” The tender lowered a red ball down a pole visible to trains 3,300 feet before the bridge to signal that the bridge was open and it was unsafe for a train to pass. Just as the bridge tender was about to close the span, however, the 8:00 express to Boston rounded the curve at 25 miles per hour. The train plunged into the river; its speed carried the engine across the western channel, where it smashed into the central pier. All cars but one fell into the river. Dr. Russell, who was in the last car, reported in The Hartford Courant (May 7, 1853), “The front of the car and part of the floor had broken off just in front of me, one end resting on the bridge and the other on the cars in the water below.”

Almost 40 victims in the first two passenger cars drowned. The crew from the Pacific pulled survivors from the water. Dr. Russell, too, aided in the rescue: “We immediately commenced taking out the inmates at the windows, and soon got out a large number, some injured, some bruised, and many, ah, far too many, dead.” Seven of those who died were Dr. Russell’s fellow doctors, including Dr. Archibald Welch of Wethersfield, president of the Connecticut Medical Association.

An inquest held Edward Tucker, the train’s engineer, negligent, since the bridge tender had displayed the signal that the bridge was open. Tucker and the train’s fireman were arrested. Although Tucker insisted he had seen the red ball aloft signaling it was safe to pass over the bridge, other witnesses testified that the ball had been lowered. Two years later, the New York & New Haven Railroad settled death claims amounting to an estimated $290,000.

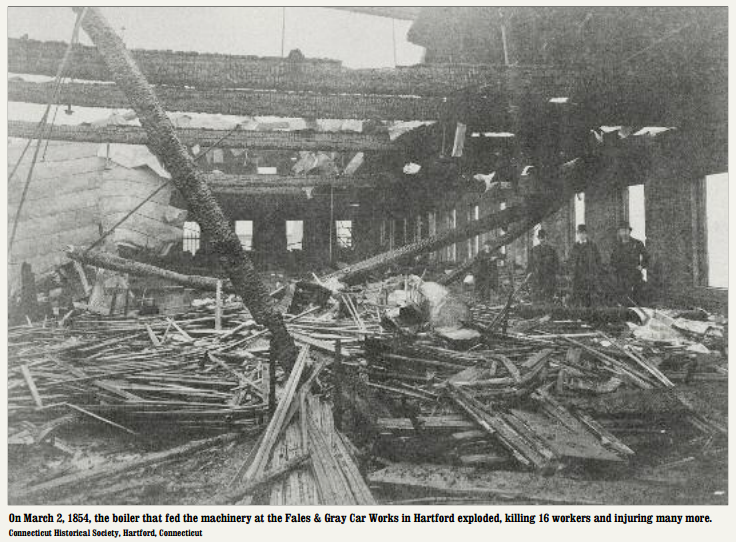

Fales & Gray Explosion: Hartford Needs a Hospital

Fales & Gray Explosion: Hartford Needs a Hospital

At 2 p.m. on March 2, 1854, the power of steam incorrectly managed and harnessed again wreaked havoc when the railroadcar factory Fales & Gray Car Works in Hartford exploded, destroying the blacksmith shop and engine room and badly damaging the main building. The New York Times (March 3, 1854) reported that Fales & Gray employed 300 people; a third of them were working in the part of the factory affected by the blast. “The explosion was most terrific— breaking the timbers of the building, powerful machinery… and prostrating the walls of the building for a hundred feet in length.” Workmen were buried in the rubble when the roof and walls caved in. Sixteen workers were killed and “a great many” injured. The cause was a new 50-horsepower boiler that had been in operation for about a month. The power of the blast killed the boiler’s engineer, John McCuen, whose arm was found “at some distance from the body.” Other victims were “horribly mutilated, and in some instancesthe bodies could scarcely be recognized.”

Ellsworth Grant, in Connecticut Disasters, relates that on the morning after the disaster, a jury inspected the site and the remains of the boiler and convened an investigation, hearing six days of testimony from workers, managers, and the boiler manufacturer. The investigation pointed to McCuen’s carelessness, which resulted in a dangerously low water level and abnormally high steam pressure. The company was also faulted for not locating the boiler room away from the employees in a separate building. It would be another 10 years, however, before the state enacted a boiler inspection law.

On the evening after the explosion, a broadside (a copy of which is in the collection of the Connecticut Historical Society) announced a citywide meeting “for the purpose of appointing a committee to raise and distribute funds for the alleviation of the wants of widows and orphans made by the late sad catastrophe.” City leaders were also moved to establish the city’s first hospital, as the lack of facilities to treat the volume and seriousness of the injuries could no longer be ignored. Hartford Hospital was established within months.

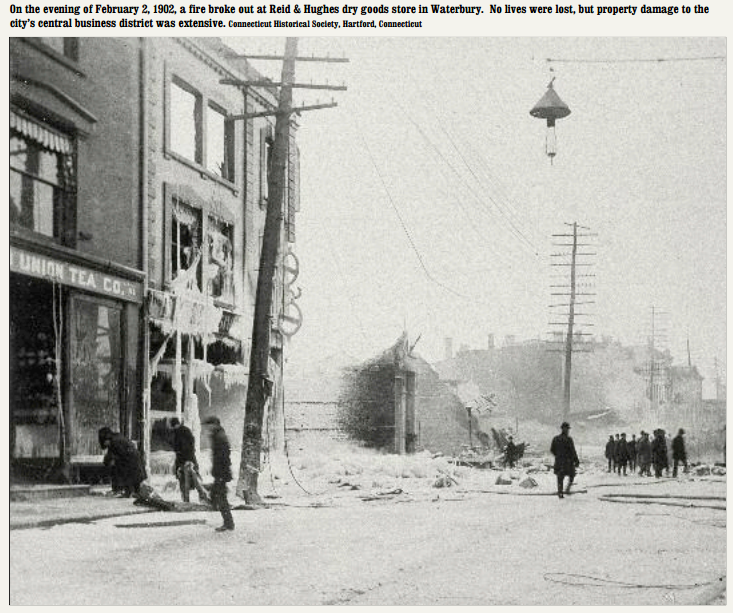

The Waterbury Fire: Six Cities Respond

The worst fire recorded in the city’s history up to that day swept through Waterbury on the stormy evening of February 2, 1902. The New York Times (February 3, 1902) reported that the fire began at Reid & Hughes dry goods store on the west side of Bank Street. Despite the cold and wet, the building was quickly engulfed in flames, and soon adjoining buildings ignited.

Eyewitness Charles Somers Miller noted in his journal, “Then a general alarm calling out the entire fire department of the city was sounded but it was to no purpose. The flames spread…, sweeping all before them to South Main street, which it crossed… . They also spread to the Franklin Hotel and burned the long row of blocks along Grand Street to Levenworth street. Chief engineer Snagg and Mayor Kilduff, seeing that the center of the City was likely to be burned out, called on Hartford, New Haven, Bridgeport, Torrington, Naugatuck, and Watertown for help, and they all responded by sending hose pipe and steamers, so at one time we had seven steamers at work. By midnight the fire seemed to be under control and I came home. At 2 a.m. I looked and could see no signs of fire but at 5 the heavens were all aglow, and the wind still blowing.”

Perhaps because the fire occurred in the evening, no injuries or fatalities were reported, but property damage to the city’s central business district was estimated by The New York Times to be at least $2 million (about $45 million today). Miller recorded that throngs of visitors came from across the state in the days following the fire to view the ruins.

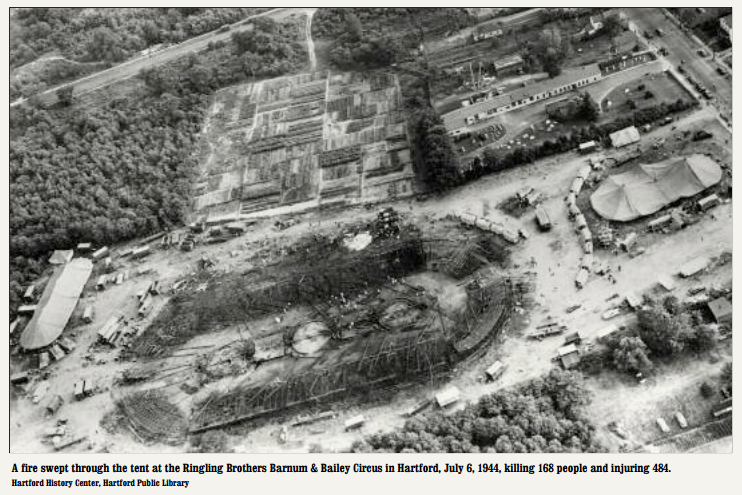

Hartford Circus Fire: “The Tent’s On Fire!”

The Hartford Circus Fire may be the worst human-caused disaster ever to have taken place in Connecticut. Thursday, July 6, 1944 was hot and humid but a fine day to see the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus in a field on Barbour Street in Hartford. Attendance was estimated at 6,000. It’s not unequivocally known how the fire started. The fire spread to the oil-impregnated canvas of the main circus tent. One of the Flying Wallendas pointed to the blaze from his perch and screamed, “The tent’s on fire!”

Chaos erupted. Ushers ran with buckets of water toward the flames, yet the fire quickly became beyond control. The crowd began running toward the exits as flaming pieces of canvas fell onto their hair and clothing. Some fought their way to the top tier of seats where they leapt 15 feet to the ground or slid down the poles and ropes. Barbara Orsini Surwilo recalled, “My father reacted quickly, [we dropped from the bleachers to the ground and]raced to the back of the tent where he and a few other men sliced the canvas….He handed my sister and I off to a large, elderly black man with huge hands who firmly gripped six or seven children in each hand. My father ran back and into the tent….He said there were about 10 men working as a team [to rescue people.]” (Connecticut Explored, formerly Hog River Journal, Fall 2006) In 10 minutes, 168 died, at least 80 of them children. Survivors included 262 who were seriously burned and 222 with other injuries.

In the field outside the tent, parents ran frantically to and fro, searching for their children. Rescuers carried bodies, some dead and some alive, and emergency aid was mobilized right away. The Bristol Press (July 7, 1944) reported that neighboring homes had “lines of men, women and children from the sidewalks to the telephone, patiently awaiting their opportunity to convey the good news of their safety.” Governor Raymond E. Baldwin personally directed rescue and relief work and “stayed on the job far into the night. Scores of soldiers from a nearby army rest camp, sent to the circus for relaxation, forgot their own injuries suffered in action overseas, to aid in numerous rescues.” According to Ellsworth Grant in Connecticut Disasters, “the Colt Armory dispatched four ambulances, four doctors, eight nurses, and twenty guards.”

The aftermath was grim. Time Magazine (July 17, 1944) reported that doctors, dentists, and jewelers were called in to help identify victims by their fillings, scars, rings, and watches. On July 6, 2005, a memorial to the victims of this terrible disaster was dedicated in the park behind Wish School; it features the names of the 168 fatal victims.

Read memories of the Hartford Circus Fire in “Memories of the Hartford Circus Fire,” Fall 2006

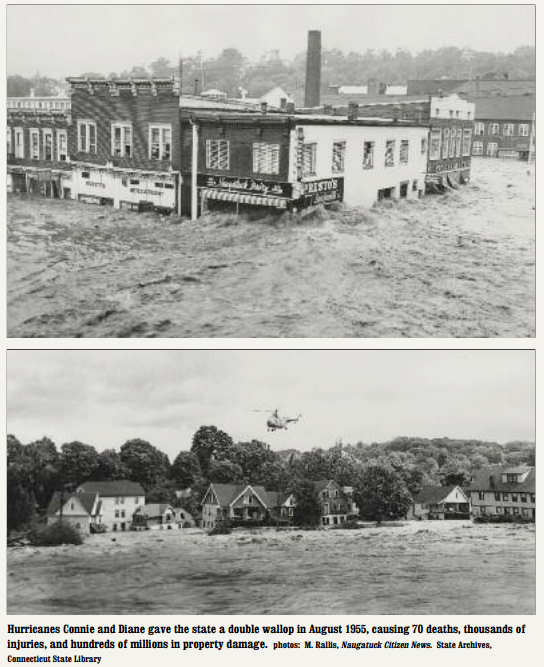

Hurricanes Connie & Diane: A Double Hit

The Flood of 1936 and Hurricane of 1938 were both devastating events, the latter causing an estimated $100 million in property damage and the loss of 85 lives. But hurricanes Connie and Diane, which struck within days of each other in August 1955, exceeded the property damage of both of those earlier major events combined. Connie struck first, on August 12 and 13, sparing the state high winds but dropping up to 8 inches of rain, particularly saturating southwestern Connecticut. Five days later, Diane arrived, pouring another 16 inches of rain on the state, hitting the Naugatuck Valley and the northwestern towns hard; northeastern towns such as Stafford Springs and Putnam were hard hit, the latter suffering from the Quinebaug Dam’s collapse in Southbridge, Massachusetts. Governor Abraham Ribicoff called the floods, reported The Hartford Courant (August 20, 1955), “the worst disaster in the state’s history” and immediately declared a state of emergency. The state highway department reported that at least 17 bridges had been destroyed, isolating communities, and that numerous roads were blocked by rock slides. Major dams broke, railroad tracks were swept away, homes and businesses were destroyed, and drinking-water supplies were compromised. The Hartford Courant also noted what eyewitnesses were seeing: “Lt. Col. Robert Schwolsky of the Connecticut National Guard reported from a helicopter: ‘I’ve never seen anything like Winsted’s Main Street. It looks like someone had taken cars and thrown them at one another,’” and another officer saw “a house, complete with lawn and landscaping, floating down the swollen river. A little later,… another house being swept by, smoke coming from its chimney.” The Connecticut National Guard was mobilized, and 16 helicopters plucked people off rooftops and out of trees. Additional helicopters were provided by the U.S. Navy, Sikorksy Aircraft in Stratford, Kaman Aircraft in Bloomfield, West Point, the First Army Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Marine Corps, rescuing hundreds of people.

The Connecticut National Guard was mobilized, and 16 helicopters plucked people off rooftops and out of trees. Additional helicopters were provided by the U.S. Navy, Sikorksy Aircraft in Stratford, Kaman Aircraft in Bloomfield, West Point, the First Army Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Marine Corps, rescuing hundreds of people.

Civil defense and emergency shelters filled quickly, and the American Red Crossset up a central disaster headquarters in Hartford. Food drops were facilitated by C-47 planes from the New York Air National Guard and the Connecticut Air National Guard.

When the event was over, according to the National Weather Service, 77 Connecticut lives were lost and property damage exceeded $350 million (www.erh.noaa.gov/ nerfc/historical/aug1955.htm).

Emma Demar was in intern from Trinity College. Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

“An Eyewitness Account of the Flood of 1936,” Fall 2002

“The Great White Hurricane of 1888,” Winter 2019-2020

“Connecticut Responds to 9/11” Fall 2011