(c) Connecticut Explored, Fall 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

President Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of war against Germany in April 1917 did not catch Connecticut divided or complacent. State munitions industries were operating at full capacity to satisfy Allied demand, as the Allies had been fighting Germany since 1914. Governor Marcus Holcomb won reelection in 1916 on a “preparedness” platform. In February 1917, Holcomb authorized a state military census of men, nurses, farms, and enemy aliens in the state, and, in March, the formation of a home guard for protection against saboteurs. After the U.S. formally entered the war, Holcomb created the State Council of Defense to mobilize citizens, industries, labor, and organizations to win the war and to disseminate propaganda.

Congress passed sedition laws in response to anti-German war hysteria and paranoid suspicion that immigrants and their children were enemy agents. At first, the large German populations in the nation were suspects, but after the Bolshevik Revolution, Russian émigrés and Jews were also viewed as potential enemy aliens.

Newspapers fueled the hysteria with stories about spies and the appearance of pro-German and pro-Bolshevik propaganda. In January 1918, the Council of National Defense sent inquiries to the state councils about the extent of this “propaganda problem.” Connecticut’s letter went to Joseph W. Alsop, secretary of the State Council  of Defense, who forwarded it to State Librarian George Godard. Alsop told him that he had replied to the letter indicating that Godard “would be able to furnish us the information in regard to this matter.” Alsop asked him to gather the information. Godard replied, “some material that is really a [sic]German propaganda is not looked upon by such by some of our librarians.” He then proposed that the state council send a letter to all public libraries to gather the librarians’ opinions. Alsop agreed, and the council formed a committee chaired by Connecticut Commissioner of Education Charles D. Hine. The letter went out from the State Council of Defense, but only about 50 librarians responded to the inquiry, and their responses provided little information.

of Defense, who forwarded it to State Librarian George Godard. Alsop told him that he had replied to the letter indicating that Godard “would be able to furnish us the information in regard to this matter.” Alsop asked him to gather the information. Godard replied, “some material that is really a [sic]German propaganda is not looked upon by such by some of our librarians.” He then proposed that the state council send a letter to all public libraries to gather the librarians’ opinions. Alsop agreed, and the council formed a committee chaired by Connecticut Commissioner of Education Charles D. Hine. The letter went out from the State Council of Defense, but only about 50 librarians responded to the inquiry, and their responses provided little information.

Still, newspapers reported on controversial literature that was appraised as enemy propaganda. In March 1918, Professor Edward E. Humphrey of Trinity College announced that he had found an example in the Hartford Public Library. The book, Inquiry into the Nature of War on the Nature of Peace (1917), was written by the controversial American economist, Thorstein Veblen. In 1899, Veblen had published The Theory of the Leisure Class, which labeled the upper 10 percent of the United States capitalist society as a “leisure class” that practiced “conspicuous consumption, ostentatious waste and idleness.” The criticism that met Inquiry was not surprising, for in it, Veblen identified global capitalism and its short-term competitive needs as the cause of the war and suggested that peace would last only under a government-controlled capitalist economy.

The Courant reported that the book was controversial at Trinity College. President Flavel Luther condemned it, as had Professor Humphrey. He worried that the book contained “socialistic” ideas and Bolshevik propaganda. He called for its removal, and a few days later Hartford Public Librarian Caroline Hewins confirmed that Inquiry was no longer on the library’s shelves. Humphrey warned that diligence about the books available in libraries should be constant because “every day I am finding things like this in our libraries, and if some of them are not treasonable, they are dangerously close to them.”

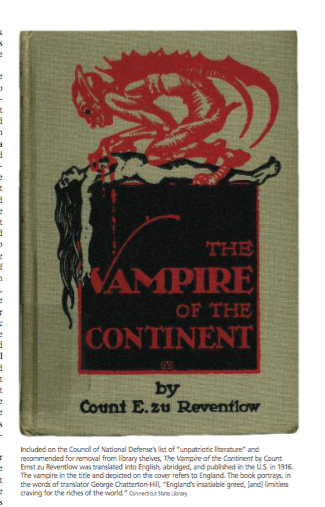

Some form of suppression of “unpatriotic” literature, if only through voluntary measures, remained a national goal, and in June 1918, the Council of National Defense sent a list of such books to all state councils. In a memorandum marked confidential, the council sought to add credence to the list by stating that it had been annotated and approved by the American Library Association. The ALA sent letters to librarians at military libraries with short lists of books it considered dangerous. “Great care should be exercised in the use of this list,” the council’s memo warned. Only librarians should receive it, they said, and books on the list should be “withdrawn temporarily from circulation.” The memo warned that “an argument or controversy over a book would give it the very publicity which it is deemed advisable to eliminate during the present period.”

Some form of suppression of “unpatriotic” literature, if only through voluntary measures, remained a national goal, and in June 1918, the Council of National Defense sent a list of such books to all state councils. In a memorandum marked confidential, the council sought to add credence to the list by stating that it had been annotated and approved by the American Library Association. The ALA sent letters to librarians at military libraries with short lists of books it considered dangerous. “Great care should be exercised in the use of this list,” the council’s memo warned. Only librarians should receive it, they said, and books on the list should be “withdrawn temporarily from circulation.” The memo warned that “an argument or controversy over a book would give it the very publicity which it is deemed advisable to eliminate during the present period.”

In July, the state council’s committee sent a cover letter and the list to Connecticut’s public and academic librarians. Only 36 librarians responded. Most who replied wrote that they had removed one or more of the books on the list from circulation. Anne Richards of the Ansonia Library reported that she had removed some books and but not those that were pro-Ally. Henry N. Sanborn, librarian of the Bridgeport Public Library, reported that the books on the list that the library owned “are now in my office, inaccessible to the public.” Emma E. Lessey, acting librarian at the Derby Public Library, said that she had removed all the books on the list and also “books written in the German language and those on the study and teaching of German, as well as any others which might be questioned.” Andrew Keogh, head librarian at Yale University, wrote that the list appeared to be intended for small public libraries and not academic libraries such as Yale’s. He noted that some books did not belong on the list and called the recommendation that, for example, all biographies of Frederick the Great and Bismarck be removed “absurd.” “It might interest you,” he continued, “to know that practically all the books in the list are already in our possession; the few that are not here will be obtained as quickly as possible, if for no other reason, as curiosities of censorship.”

The state council made no further attempts to involve librarians in the suppression of books. There was not enough time to do so, anyway, because the Armistice was signed four months later. The replies were filed in the records of the state council and forgotten and now reside in the State Archives for use by researchers.

The state council made no further attempts to involve librarians in the suppression of books. There was not enough time to do so, anyway, because the Armistice was signed four months later. The replies were filed in the records of the state council and forgotten and now reside in the State Archives for use by researchers.

Mark H. Jones was the state archivist at the Connecticut State Library from 1982 to 2013. This article is based on “Winning the War Without Some Books,” CONNector (November 1999), a publication of the Connecticut State Library (used with permission).

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page

Return to Fall 2014: The Power of the Pen