By Walter W. Woodward

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2011 Volume 9 Number 4

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Everyone who reads this has lived through some of them. Some of us have lived through many of them. They are events of such profound impact that they are seared into our memories the instant we hear about them. They change our world, and the very news of their occurrence changes us. Ever after, we connect such events with the moment when, and the place where, we learned about them.

Everyone who reads this has lived through some of them. Some of us have lived through many of them. They are events of such profound impact that they are seared into our memories the instant we hear about them. They change our world, and the very news of their occurrence changes us. Ever after, we connect such events with the moment when, and the place where, we learned about them.

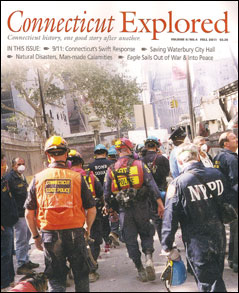

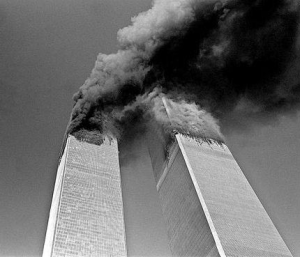

Where were you. . . when the second aircraft slammed into the World Trade Center? Where were you when the Challenger exploded? When Bobby Kennedy was killed? When Martin Luther King was shot? When JFK was assassinated?

In our lifetime, news of such tragedies has often been accompanied by media images that become icons of our memories: Smoke mountains billowing from the collapsing towers; starburst contrails in the sky over Cape Canaveral; a four year old giving his father’s casket a farewell salute. These, too, become essential parts of our recollections. Like the moment when and the place where, the image of is also deeply woven into our where were you stories.

But what about the major events that occurred long ago, before the years of instant news? What about the accounts that were received hours or even days after an event had taken place? Did these already-dated stories strike people with the same kind of unforgettable impact as today’s breaking news, or did the distance imposed by time soften the blow? The 1865 diary of Ives W. Hart, of East Meriden, Connecticut, preserved and transcribed by his great-granddaughter Sue Hart, suggests that—at least in one case—the personal response to news of sudden, awful events remained great, whether the blow was delayed or presented without riveting images.

But what about the major events that occurred long ago, before the years of instant news? What about the accounts that were received hours or even days after an event had taken place? Did these already-dated stories strike people with the same kind of unforgettable impact as today’s breaking news, or did the distance imposed by time soften the blow? The 1865 diary of Ives W. Hart, of East Meriden, Connecticut, preserved and transcribed by his great-granddaughter Sue Hart, suggests that—at least in one case—the personal response to news of sudden, awful events remained great, whether the blow was delayed or presented without riveting images.

Hart, a 23-year-old farmer, made daily entries in his diary for 65 years. With very few exceptions, these entries are matter-of-fact accounts of the hard daily labor of farm life. Tues, Apr. 4 (1865): Plowed half a day but ground was wet. Finished seeding brook meadow hay. . . Thurs. Apr. 6: Mended fence in the forenoon and plowed a little. The grass is growing fast; it is quite green. . . .Such is the standard fare of Hart’s diary entries. But on April 15, 1865, the entries take a sudden turn. I plowed for father all day & Edmund painted the garden fence, Hart wrote. But then he added, We heard that president Lincoln was shot last night.

How and when did Hart learn the news of Lincoln’s assassination the previous day? The diary is silent on this point. But the next day, a somber Hart shared collective sorrow with his community. April 16 . . . I went to church today. . . . The people feel very sad on account of Mr. Lincoln’s death. Mr. Seward was stabbed. Two days after that, the normally mundane journal entry noted a pageant of collective national grief. Wed. Apr. 19 President Lincoln was buerried yesterday; the stores and shops were all closed and there were meetings in the churches over the north. Strikingly, this entry was underlined; a singular recognition of its magnitude.

In 1865, 1963, 2001, and presumably all the years ahead of us, too, the power of tragedy to etch itself instantaneously and irrevocably into our memory is a constant. Terrible things leave terrible scars, in fact and in memory.

God spare us from too many where were you days.