(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2016

SUBSCRIBE/Buy the Issue!

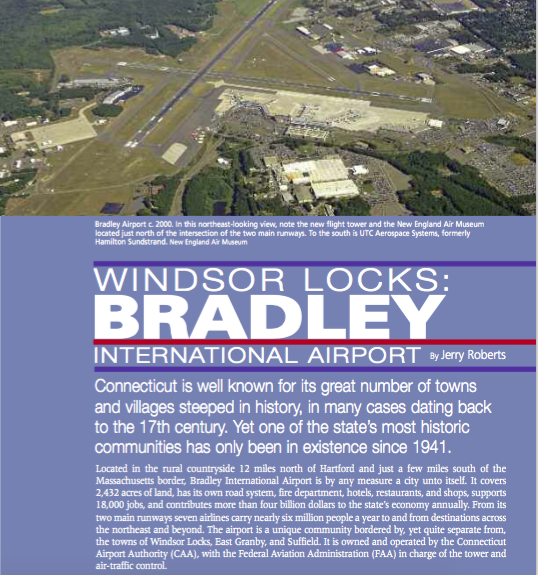

Connecticut is well known for its great number of towns and villages steeped in history, in many cases dating back to the 17th century. Yet one of the state’s most historic communities has only been in existence since 1941. Located in the rural countryside 12 miles north of Hartford and just a few miles south of the Massachusetts border, Bradley International Airport is by any measure a city unto itself. It covers 2,432 acres of land, has its own road system, fire department, hotels, restaurants, and shops, supports 18,000 jobs, and contributes more than four billion dollars to the state’s economy annually. From its two main runways seven airlines carry nearly six million people a year to and from destinations across the northeast and beyond. The airport is a unique community bordered by, yet quite separate from, the towns of Windsor Locks, East Granby, and Suffield. It is owned and operated by the Connecticut Airport Authority (CAA), with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in charge of the tower and air-traffic control.

Connecticut is well known for its great number of towns and villages steeped in history, in many cases dating back to the 17th century. Yet one of the state’s most historic communities has only been in existence since 1941. Located in the rural countryside 12 miles north of Hartford and just a few miles south of the Massachusetts border, Bradley International Airport is by any measure a city unto itself. It covers 2,432 acres of land, has its own road system, fire department, hotels, restaurants, and shops, supports 18,000 jobs, and contributes more than four billion dollars to the state’s economy annually. From its two main runways seven airlines carry nearly six million people a year to and from destinations across the northeast and beyond. The airport is a unique community bordered by, yet quite separate from, the towns of Windsor Locks, East Granby, and Suffield. It is owned and operated by the Connecticut Airport Authority (CAA), with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in charge of the tower and air-traffic control.

Though landlocked by farmland and urban sprawl, Bradley functions much like the great seaports that were once our primary means of long-distance transportation for both people and trade goods. Airports, it can be argued, are in fact the new seaports, and Bradley, or BDL as it is known in aviation circles, is Connecticut’s portal to the world. On the other hand, the signs that welcome people to the airport feature the phrase “Gateway to New England,” a tagline traditionally associated with the Connecticut River, which flows nearby and once carried commerce and passengers into the heart of New England from the sea. It is now the airways that connect us. Just seven decades ago the area now occupied by the airport was still covered by rural farmland, including shade-grown tobacco fields and small family farms. Compared to nearby Windsor, first settled in 1633, Bradley’s footprint within Connecticut’s cultural timeline is quite small. Yet the rapid evolution of this jet-age city-state in the midst of New England’s agricultural heartland is both dramatic and historically significant in its own right.

The story begins in the summer of 1940. Most of Europe had been overrun by Hitler’s war machine. The Royal Air Force was fighting for its life against Germany’s Luftwaffe in the skies above England. It was becoming clear that even on our side of the Atlantic some sort of defense might be necessary. If war came from the air, New England’s industries and important cities, including Hartford, could certainly be vulnerable. From arms manufacturers such as Colt to Pratt & Whitney’s East Hartford aircraft engine production facilities, this was a very strategic area in terms of national defense. The proximity of other important industries, including the headquarters of the nation’s largest insurance companies in Hartford, made it clear that something had to be done.

Anticipating the need for a number of defensive air bases along the eastern seaboard, the U.S. Army began looking for a suitable location in central Connecticut. Although the obvious choice appeared to be Hartford’s Brainard Airfield, the state’s largest airport at the time, the army soon realized that the site, hemmed in by the Connecticut River, flood dykes, and power lines, would not allow for expansion into a full-blown military air base. Aerial surveys, however, revealed that the flat farmland near Windsor Locks offered an ideal location. Connecticut Governor Robert A. Hurley embraced the idea and in January 1941 introduced emergency legislation for the state to purchase 1,681 acres of farmland for $250,000. The property would in turn be leased to the federal government for a dollar a year for 25 years, with options extending well into the 1960s. The army immediately opened an office in the Windsor Locks Memorial Hall as a temporary headquarters and began planning the new facility.

Congress quickly authorized $2.6 million for construction of the Windsor Locks Air Base. It would be one of a string of primary bases including Mitchel Field on Long Island and facilities in Manchester, New Hampshire and Bangor, Maine. Smaller, auxiliary fields would be located in New Haven, Bridgeport, Groton, Rentschler Field in East Hartford, Suffolk, Long Island, and Hillsgrove, Rhode Island. Together these airfields would provide for New England’s air defense under the command of the army’s First Air Force.

Construction of the Windsor Locks base began on March 7, 1941. Thirty army engineers directed 1,800 laborers who worked day and night, clearing, leveling, and paving hundreds of acres of farmland. Route 20 had to be relocated, and 50 homes were moved or demolished to make way for the three runways, the largest of which would be 5,230 feet long. Housing all of the construction workers put a great strain on local accommodations, and residents in the surrounding communities were encouraged to rent out spare rooms. The base soon grew into a veritable city, with 36 barracks, 8 mess halls, 5 officers’ quarters, 10 supply buildings, a 17-building hospital complex, a telephone exchange, motor pool, and recreation hall, a large hangar and control tower, a school, a fire station, maintenance buildings, and more. In addition to the runways and taxi aprons there were 26 miles of roadways, 19 miles of water mains, a massive sewer system, and housing to accommodate 8,000 officers and enlisted men.

Construction of the Windsor Locks base began on March 7, 1941. Thirty army engineers directed 1,800 laborers who worked day and night, clearing, leveling, and paving hundreds of acres of farmland. Route 20 had to be relocated, and 50 homes were moved or demolished to make way for the three runways, the largest of which would be 5,230 feet long. Housing all of the construction workers put a great strain on local accommodations, and residents in the surrounding communities were encouraged to rent out spare rooms. The base soon grew into a veritable city, with 36 barracks, 8 mess halls, 5 officers’ quarters, 10 supply buildings, a 17-building hospital complex, a telephone exchange, motor pool, and recreation hall, a large hangar and control tower, a school, a fire station, maintenance buildings, and more. In addition to the runways and taxi aprons there were 26 miles of roadways, 19 miles of water mains, a massive sewer system, and housing to accommodate 8,000 officers and enlisted men.

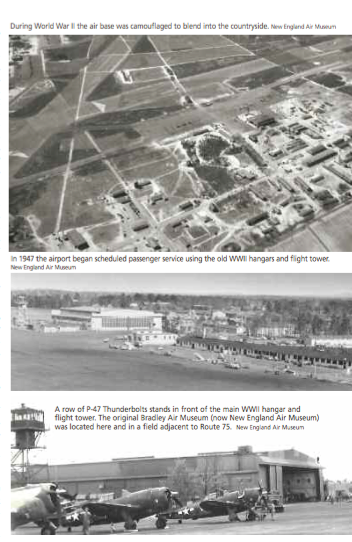

As the expansive facility began to redefine the rural countryside, a unique feature would set the Windsor Locks base apart from all others in the United States. It was the first air base designed from its inception to be totally invisible from the air. This was achieved by leaving surrounding farmlands as intact as possible, complete with their old barns and farmhouses. The runways and taxi aprons were painted with a simulated patchwork of crops and country lanes to match the surrounding landscape and break up the straight lines of the base roads and tarmac. The camouflage was so effective that many arriving pilots had trouble finding the airfield even when they were directly over it. This problem continued after the war when commercial airline pilots occasionally found it difficult to find the airport.

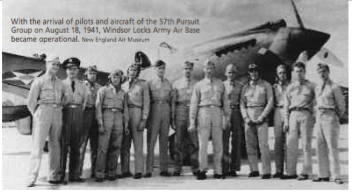

In July, with the construction phase nearing completion, military command and logistics personnel began to arrive. At last, on August 18, 1941, the three squadrons of the 57th Pursuit Group arrived from Mitchel Field with their P-40 Tomahawk fighter aircraft. On this day, just five months after construction began, the Windsor Locks Army Air Base was officially declared operational. This phenomenal transition from tobacco field to air base was a testimony to the focusing of resources and the expediency of war. Incredibly, this same transition was taking place in several hundred other locations around the country.

In July, with the construction phase nearing completion, military command and logistics personnel began to arrive. At last, on August 18, 1941, the three squadrons of the 57th Pursuit Group arrived from Mitchel Field with their P-40 Tomahawk fighter aircraft. On this day, just five months after construction began, the Windsor Locks Army Air Base was officially declared operational. This phenomenal transition from tobacco field to air base was a testimony to the focusing of resources and the expediency of war. Incredibly, this same transition was taking place in several hundred other locations around the country.

One of the newly arrived pilots was 24-year-old Second Lieutenant Eugene Bradley. Born and raised in Oklahoma, Bradley had enlisted in September 1940 and applied for Army Air Corps flight training. He received his pilot’s wings in May, at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas. A few days later he married his Texas sweetheart, Ann Blackerwick, and was assigned to the 64th Squadron of the 57th Pursuit Group then forming up at Mitchel Field, Long Island. The young couple headed east.

Two months later, on August 19, Bradley and Ann, who was now pregnant, moved with the squadron from Long Island to the new Windsor Locks base and took an apartment in town. Two days later Bradley joined his squadron commander for some mock dog-fighting practice over the airfield. During a tight turn Bradley apparently blacked out from extreme G-forces at 10,000 feet and went into a spin. Despite desperate radio calls from the commander telling Bradley to bail out, the P-40, with its unconscious pilot still strapped into the cockpit, crashed into the woods surrounding the field, embedding the aircraft six feet into the ground. Eugene and Ann Bradley had only been in Connecticut three days.

A few weeks after the fatal crash the Hartford Times carried an editorial suggesting the base be named for the young pilot, and many agreed. By January 1942 the airfield was officially re-named Army Air Base, Bradley Field, Connecticut. Despite attempts after the war to rename the airport, Bradley International Airport continues to bear the name of the young man who came east from Oklahoma to defend his country. During the course of the war more than 20 pilots were killed in training crashes at the airfield.

Throughout the remainder of 1941 the base functioned in peacetime mode, but everything changed on December 7 as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the United States directly into World War II. Within a week the three squadrons of the 57th were dispersed to Groton, Boston, and Farmingdale, Long Island to provide a broader air defense. By July of 1942, however, it was clear that the east coast was no longer under threat of direct aerial attack. The 57th fighter group was shipped half way around the world to provide combat air support to the British as they fought their way east across North Africa from El-Aleman into Tunisia, where Germany’s once vaunted desert army was forced to withdraw from the continent as newly arrived American troops pushed in from the west. The 57th then crossed into Italy to continue the war effort under American command.

Meanwhile, Bradley Field had become a major training base for new combat units ramping up for deployment into war zones. Aircraft of all kinds, including fighters, bombers, and transports, could now be seen on the base along with a wide range of specialized units. By 1943 the base housed more than 8,000 officers and enlisted men and employed another 1,300 civilians in a wide range of roles. Hundreds of women, both civilian and uniformed, now worked on the base as well. In fact, more than 40 percent of the civilian mechanics were women.

By 1944 the base switched from training air combat units to the training of replacement pilots for units already deployed. By now the base also featured a POW camp, where German and Italian prisoners would spend the balance of the war (see “German POWs at Bradley Field,” Winter 2003-2004, Vol. 2, #1).

When the war in Europe ended in May 1945 Bradley became a major point of disembarkation where hundreds of aircraft and their crews arrived directly from the European theater. Bradley Field was often the first place these war-weary men set foot on American soil after their combat tours overseas. Most were given 30 days leave before being reassigned, often to the Pacific, where the war still raged. The aircraft were ferried off for repairs and refurbishment.

At last, in 1947, nearly two years after the war had ended, the base was handed back to the state of Connecticut and began its next phase as a commercial airport. On April 1, 1947, flight 624, an Eastern Airlines DC-3, became the first scheduled passenger arrival, piloted by WW1 ace Eddy Rickenbacker, then president of Eastern.

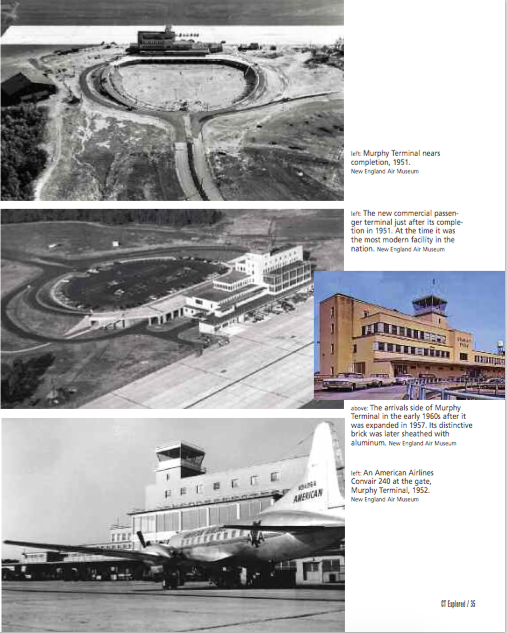

For the first several years the airlines had to make do with the facilities the army had left behind, but construction soon began on a new air terminal. In 1951 it was dedicated by President Dwight Eisenhower, Charles Lindbergh, and Pratt & Whitney founder Fred Rentschler. Named for Francis Murphy, the first chairman of the Connecticut Aeronautics Commission, it was the most modern air terminal in the country at the time it was built. Sixty years later, in 2010, when it was at last decommissioned, it was the oldest major passenger terminal still in operation. It had already been replaced by Terminal A, which was built in 1986. Today, seven airlines — American, Jet-Blue, Southwest, Air Canada, Delta, United, and OneJet — now operate out of Bradley, with routes reaching as far as the west coast and Montreal, Toronto, and Cancun. Although a Northwest Airlines attempt to maintain direct service to Amsterdam in 2007 did not prove sustainable due the recession and high fuel prices at the time, Aer Lingus will begin service to Dublin, Ireland in September 2016. This new transatlantic route will help reinforce the international in Bradley International Airport. Serving as the primary backup airport to Boston’s Logan and New York’s JFK, Bradley has served jumbo jets and even the Concorde.

For the first several years the airlines had to make do with the facilities the army had left behind, but construction soon began on a new air terminal. In 1951 it was dedicated by President Dwight Eisenhower, Charles Lindbergh, and Pratt & Whitney founder Fred Rentschler. Named for Francis Murphy, the first chairman of the Connecticut Aeronautics Commission, it was the most modern air terminal in the country at the time it was built. Sixty years later, in 2010, when it was at last decommissioned, it was the oldest major passenger terminal still in operation. It had already been replaced by Terminal A, which was built in 1986. Today, seven airlines — American, Jet-Blue, Southwest, Air Canada, Delta, United, and OneJet — now operate out of Bradley, with routes reaching as far as the west coast and Montreal, Toronto, and Cancun. Although a Northwest Airlines attempt to maintain direct service to Amsterdam in 2007 did not prove sustainable due the recession and high fuel prices at the time, Aer Lingus will begin service to Dublin, Ireland in September 2016. This new transatlantic route will help reinforce the international in Bradley International Airport. Serving as the primary backup airport to Boston’s Logan and New York’s JFK, Bradley has served jumbo jets and even the Concorde.

Not often seen by passengers rushing to get to their flights are the other major portions of the airport complex that include both military and transport operations. Bradley is designated as a split-use civilian/military facility and is also home to the Connecticut Air National Guard and the Army Air National Guard. Fed-Ex, UPS, and DHL operate transport hubs at Bradley, while Signature Flight Services operates a separate terminal for corporate aircraft. Aircraft manufacturers Bombardier and Embraer Executive Jets also maintain major factory service centers here for their corporate and passenger aircraft.

Two of the most iconic members of the extended Bradley community are Kaman Aircraft and Hamilton Sundstrand (formerly Hamilton Standard, now UTC Aerospace). Both of these important aerospace companies maintain flagship facilities here. Kaman originally began building helicopters soon after World War II in the air base’s old gymnasium. It continues to design and build helicopters and components nearby, critical to several other defense contractors. Hamilton Standard was the nation’s leading producer of aircraft propellers before and during the war. Now the company designs and builds life-support systems for spacecraft and space suits and a new engineering and research facility has just been opened here. These two companies, along with Sikorsky in Bridgeport and Pratt & Whitney in East Hartford, along with dozens of smaller companies that feed the aerospace industry, maintain the state’s ongoing role in aerospace engineering.

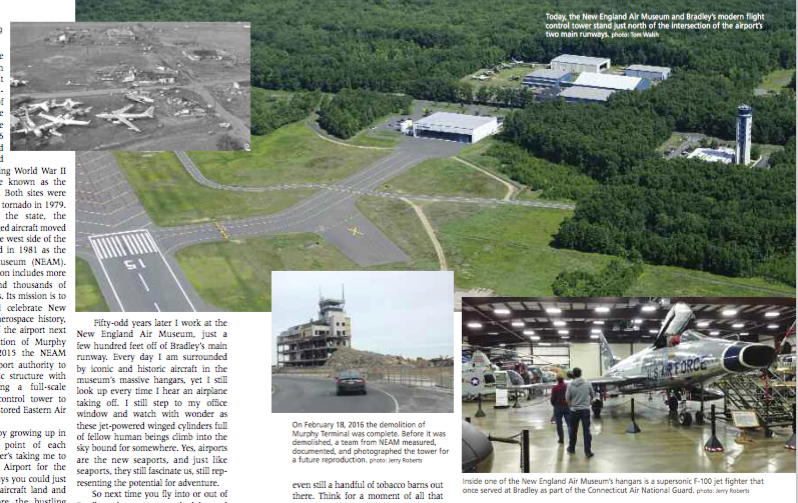

In the 1959 the Connecticut Aviation Historical Association was established to study and preserve Connecticut’s aviation legacy. Eventually it amassed a large outdoor collection of aircraft across from the airport’s main entrance on Route 75. In 1976 additional aircraft and displays were installed in one of the remaining World War II hangars. This became known as the Bradley Air Museum. Both sites were heavily damaged by a tornado in 1979. With support from the state, the museum and its salvaged aircraft moved to a 56-acre site on the west side of the airport and re-opened in 1981 as the New England Air Museum (NEAM). Today NEAM’s collection includes more than 100 aircraft and thousands of artifacts in six hangars. Its mission is to preserve, study, and celebrate New England’s incredible aerospace history, including the story of the airport next door. As the demolition of Murphy Terminal began in 2015 the NEAM worked with the airport authority to document the historic structure with the goal of building a full-scale reproduction of its control tower to display alongside a restored Eastern Air Lines DC-3.

When I was a boy growing up in Michigan the high point of each birthday was my father’s taking me to Detroit Metropolitan Airport for the afternoon. In those days you could just walk around, watch aircraft land and take off, and explore the bustling terminals. I loved to imagine where people were going and where they had come from. Here were men, women, and children embarking on airborne voyages to destinations across the country and around the globe, and I hoped to do the same one day.

Fifty-odd years later I work at the New England Air Museum, just a few hundred feet off of Bradley’s main runway. Every day I am surrounded by iconic and historic aircraft in the museum’s massive hangars, yet I still look up every time I hear an airplane taking off. I still step to my office window and watch with wonder as these jet-powered winged cylinders full of fellow humans beings climb into the sky bound for somewhere. Yes, airports are the new seaports, and just like seaports, they still fascinate us, still representing the potential for adventure.

So next time you fly into or out of Bradley, take a moment to look beyond the parking garages, ticketing desks, and security screening points. If you get a chance, look out the window and take in the sprawling complex still bordered by a bit of the farmland upon which an air base was built in 1941. Yes, there are even still a handful of tobacco barns out there. Think for a moment of all that has taken place here in the past seven decades: the people, the aircraft, and the history that now co-exists with this jet-age portal to the world, the future…. and sometimes even the past.

Jerry Roberts is the executive director of the New England Air Museum.

This article is based in part on Tom Palshaw’s Bradley Field: The First 25 Years (New England Air Museum, 1998). Tom is a retired aviation technician who now volunteers with NEAM’s aircraft restoration and research teams.

Explore!

New England Air Museum

36 Perimeter Road, Windsor Locks

neam.org, 860-623-3305

Listen to our interview with Jerry Roberts on Grating the Nutmeg, the podcast of Connecticut history!

http://gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com/14-bradley-field-and-eugene-bradley

Read more about the New England Air Museum in Jerry’s article in the Summer 2015 issue: ctexplored.org/preserving-connecticuts-aeronautical-history/

German POWs at Bradley Field, Winter 2003-2004

Read more stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page.

Subscribe to receive every issue of Connecticut Explored.