By Mary M. Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Quick: name some of Connecticut’s major contributions to civilization. Otis’s elevators. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Wooster Street’s pizza. And Dickinson’s witch hazel. Wait what… Witch hazel?

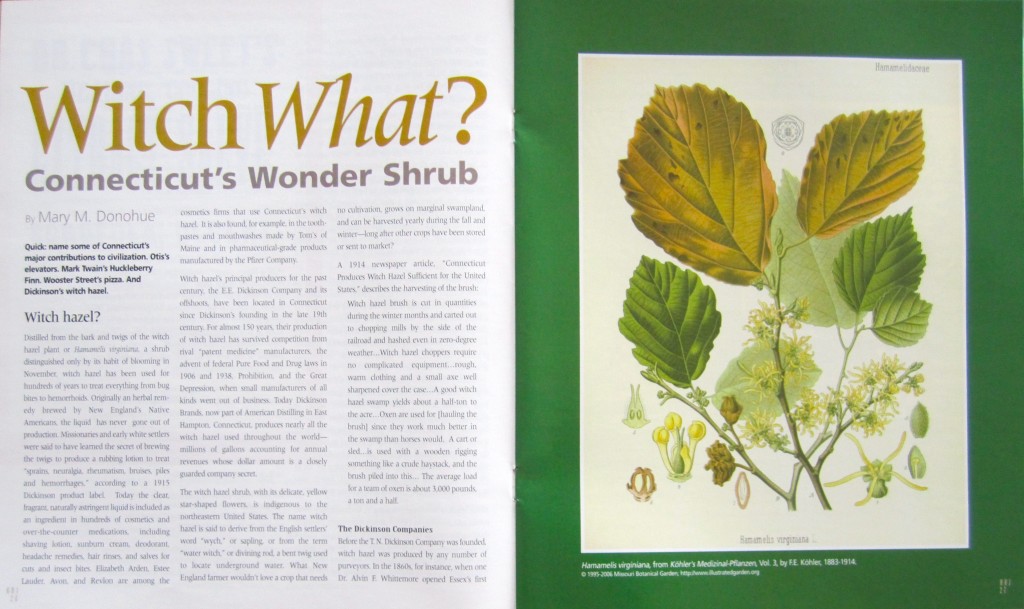

Distilled from the bark and twigs of the witch hazel plant or Hamamelis virginiana, a shrub distinguished only by its habit of blooming in November, witch hazel has been used for hundreds of years to treat everything from bug bites to hemorrhoids. Originally an herbal remedy brewed by New England’s Native Americans, the liquid’s never since gone out of production. Missionaries and early white settlers were said to have learned the secret of brewing the twigs to produce a rubbing lotion to treat “sprains, neuralgia, rheumatism, bruises, piles and hemorrhages,” according to 1915 Dickinson product label. Today the clear, fragrant, naturally astringent liquid is used to treat dozens of conditions and is included as an ingredient in hundreds of cosmetics and over-the-counter medications, including shaving lotion, sunburn cream, deodorant, headache remedies, hair rinses, and salves for cuts and insect bites. Elizabeth Arden, Estee Lauder, Avon, and Revlon are among the cosmetics firms that use Connecticut’s witch hazel. It is also found, for example, in the toothpastes and mouthwashes made by Tom’s of Maine and in pharmaceutical-grade products manufactured by the Pfizer Company.

Witch hazel’s principal producers for the past century, the E.E. Dickinson Company and its offshoots, have been located in Connecticut since Dickinson’s founding in the late 19th century. For almost 150 years, their production of witch hazel has survived competition from rival “patent medicine” manufacturers and from foreign producers, the advent of federal Pure Food and Drug laws in 1906 and 1938, Prohibition, and the Great Depression, when small manufacturers of all kinds went out of business. Today Dickinson Brands, now part of American Distilling in East Hampton, Connecticut, produces nearly all the witch hazel used throughout the world—millions of gallons accounting for annual revenues whose dollar amount is a closely guarded company secret.

The witch hazel shrub, with its delicate, though unremarkable, yellow star-shaped flowers, is indigenous to the northeastern United States. The name witch hazel is said to derive from the English settlers’ word “wych,” or sapling, or from the term “water witch,” or divining rod, a bent twig used to locate underground water. What New England farmer wouldn’t love a crop that needs no cultivation, grows on marginal swampland, and can be harvested yearly during the fall and winter—long after other crops have been stored or sent to market?

The witch hazel shrub, with its delicate, though unremarkable, yellow star-shaped flowers, is indigenous to the northeastern United States. The name witch hazel is said to derive from the English settlers’ word “wych,” or sapling, or from the term “water witch,” or divining rod, a bent twig used to locate underground water. What New England farmer wouldn’t love a crop that needs no cultivation, grows on marginal swampland, and can be harvested yearly during the fall and winter—long after other crops have been stored or sent to market?

A 1914 newspaper article, “Connecticut Produces Witch Hazel Sufficient for the United States,” describes the harvesting of the brush:

Witch hazel brush is cut in quantities during the winter months and carted out to chopping mills by the side of the railroad and hashed even in zero-degree weather…Witch hazel choppers require no complicated equipment…rough, warm clothing and a small axe well sharpened cover the case…A good witch hazel swamp yields about a half-ton to the acre…Oxen are used for [hauling the brush]since they work much better in the swamp than horses would. A cart or sled…is used with a wooden rigging something like a crude haystack, and the brush piled into this… The average load for a team of oxen is about 3,000 pounds, a ton and a half.

The Dickinson Companies

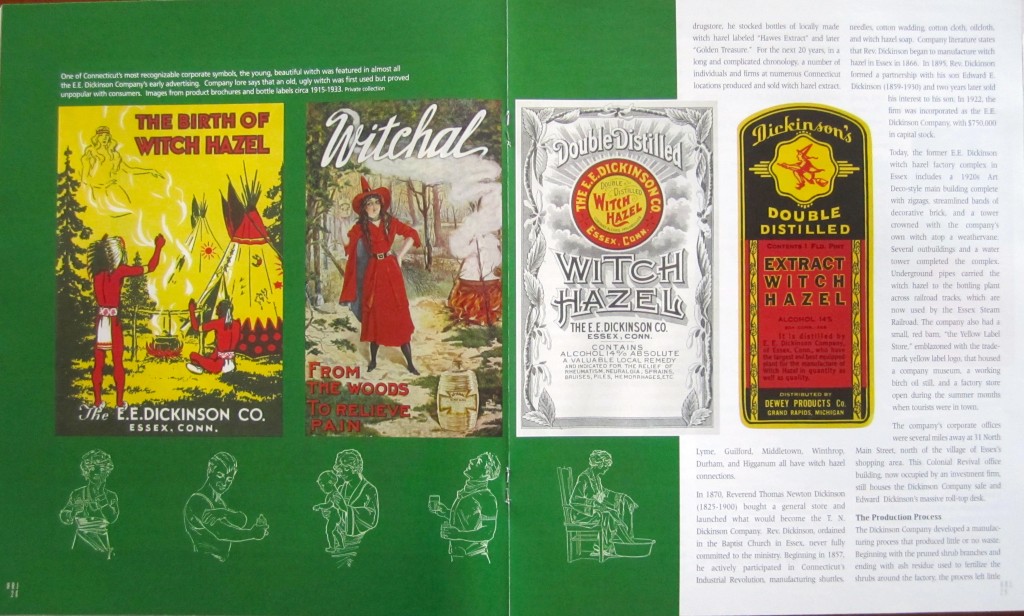

Before the T.N. Dickinson Company was founded, witch hazel was produced by any number of purveyors. In the 1860s, for instance, when one Dr. Alvin F. Whittemore opened Essex’s first drugstore, he stocked bottles of locally made witch hazel labeled “Hawes Extract” and later “Golden Treasure.” For the next 20 years, in a long and complicated chronology, a number of individuals and firms at numerous Connecticut locations produced and sold witch hazel extract. Lyme, Guilford, Middletown, Winthrop, Durham, and Higganum all have witch hazel connections.

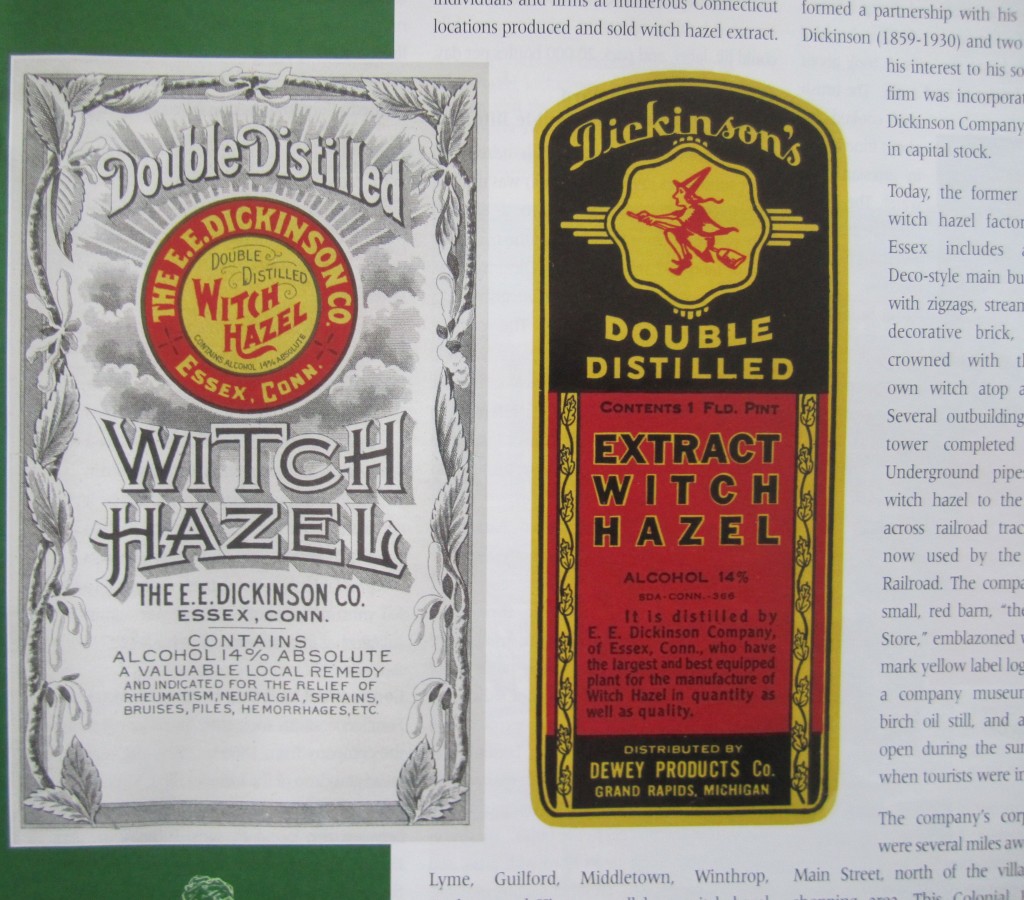

In 1870, Reverend Thomas Newton Dickinson (1825-1900) bought a general store and launched what would become the T. N. Dickinson Company. RevDickinson, ordained in the Baptist Church in Essex, never fully committed to the ministry. Beginning in 1857, he actively participated in Connecticut’s Industrial Revolution, manufacturing shuttles, needles, cotton wadding, cotton cloth, oilcloth, and witch hazel soap. Company literature states that Rev. Dickinson began to manufacture of witch hazel in Essex in 1866. In 1895, Rev. Dickinson formed a partnership with his son Edward E. Dickinson (1859-1930) and two years later sold his interest to his son. In 1922, the firm incorporated as the E.E. Dickinson Company, with $750,000 in capitol stock.

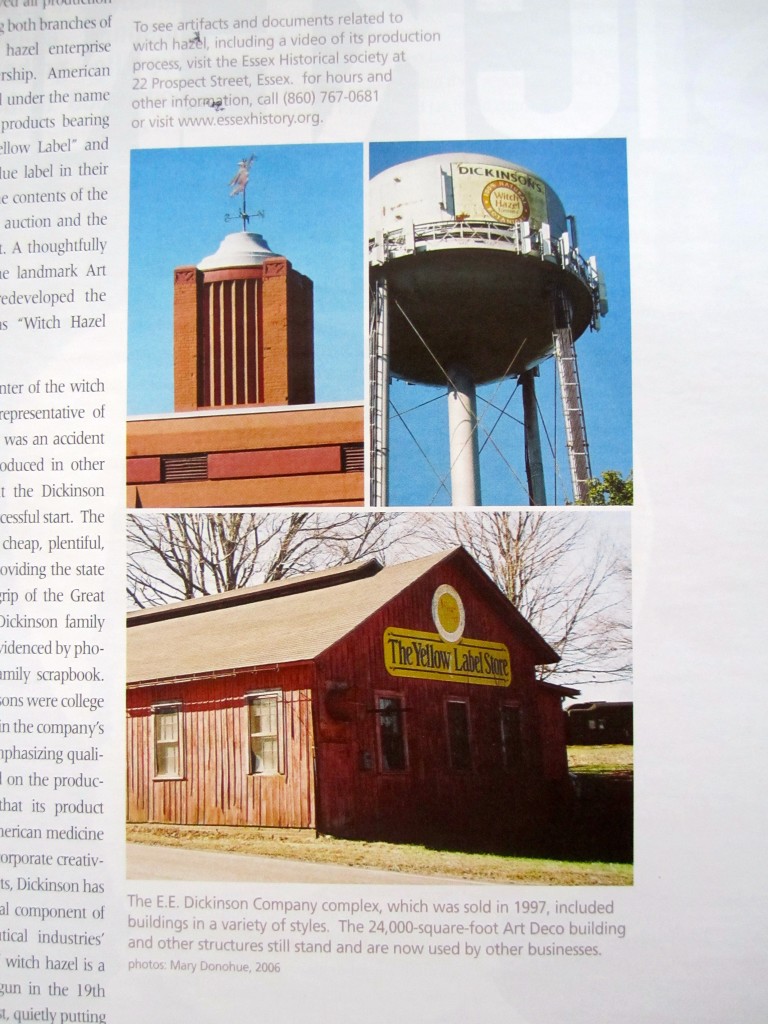

Today, the former E.E. Dickinson witch hazel factory complex in Essex includes a 1920s Art Deco-style main building complete with zigzags, streamlined bands of decorative brick, and a tower crowned with the company’s own witch atop a weathervane. Several outbuildings and a water tower completed the complex. Underground pipes carried the witch hazel to the bottling plant across railroad tracks, which are now used by the Essex Steam Railroad. The company also had a small, red barn, “the Yellow Label Store,” emblazoned with the trademark yellow label logo, that housed a company museum, a working birch oil still, and a factory store open during the summer months when tourists were in town.

The company’s corporate offices were several miles away at 31 North Main Street, north of the village of Essex’s shopping area. This Colonial Revival office building, now occupied by an investment firm, still houses the Dickinson Company safe and Edward Dickinson’s massive roll-top desk.

The Production Process

The Dickinson Company developed a manufacturing process that produced little or no waste. Beginning with the pruned shrub branches and ending with ash residue used to fertilize the shrubs around the factory, the process left little of the environmental toxins of other industries like the textile or metalworking industries. At the main building, chopped and shredded twigs were stored in an open loading dock. A worker would scoop up the brush and dump it into a hopper that fed a conveyor belt. The shredded brush was loaded into the stills. It took about 1,400 pounds of twigs to load a still. The brush was cooked for about nine hours in artesian well water. The distillation began after about an hour of cooking. Live steam heated the stills. A pipe ran out of the top of each still to draw off the extract. From there, an efficient well designed production line kept the distilled liquid moving through the condenser pipes to a stainless steel collecting tank. When the collecting tank was full, a workman would open a valve to drain the extract into a larger tank in the basement. It was mixed en route with grain alcohol, which acts as a preservative.

The used branches were then fed into huge boilers, thus producing the live steam needed to cook and distill the next batch. In 1954, the factory had three storage tanks for the witch hazel-alcohol mixture holding from 8,250 to 31,500 gallons each. In 1980, the company newsletter noted that the hand-operated bottling operation, running one shift, could fill, label, and pack 20,000 bottles per day.

The Dickinson Standard “Double Distilled, Not Double Diluted”

Moving from an era when witch hazel (and other substances involving alcohol) was distilled in unregulated back-yard stills to a time of increasing government scrutiny of the manufacture of food and medicines, the Dickinson Co. always stressed the quality and integrity of its product. The company’s slogan, “Double Distilled, not Double Diluted” referred to Dickinson’s insistence on high production standards, which included harvesting only the best-quality bushes and only during their peak season, using pure water and pure alcohol, distilling the extract not once but twice, bottling it at full strength (not diluted), and maintaining sanitary handling and bottling conditions from the start of the process to the finish. Dickinson used copper piping, tanks lined with glass, and shipping barrels with an inner coating of paraffin to protect its product against contamination.

At the turn of the 19th century, thousands of so-called “patent” medicines claimed to cure almost anything, including cancer, diabetes, gallstones, and weak hearts. They could contain drugs such as opium, morphine, heroin, or cocaine without noting that on the bottle. The 1906 federal Food and Drugs Act prohibited the manufacture and interstate shipment of “adulterated” and “misbranded” foods and drugs. The law was expanded and strengthened in 1938 with the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which dictated some 40 improvements, including regulating cosmetics for the first time, requiring that drug manufacturers provide scientific proof that their products could be used safely, and making false claims illegal.

And while the federal pure food and drug standard early in the 20th century required 8.3 pounds of brush to the gallon, the Dickinson plant prided itself on using up to 20 pounds per gallon. The 1914 newspaper article cited above noted that

Standards of purity which have come in under the pure food and drug act … have made a big difference … . Before there was a good deal of witch hazel extract on the market that never saw a swamp. It is comparatively easy to run alcohol through shavings and flavor it with acetic acid and produce a fluid which smells like witch hazel … it is a profitable trick of business economy to substitute wood alcohol for grain alcohol in commercial witch hazel.

Connecticut Still Dominates the Market

Four generations took their turns at operating the company from 1866 to 1979, the year the great-grandson of the founder died. But, as with many family businesses, a rift developed between the founder’s sons Thomas, Jr. and Edward Everett. After Rev. Dickinson’s death, the larger operation in Essex went to Edward and Thomas inherited the smaller stills scattered throughout the state, bringing them together under the name T.N. Dickinson. A 1987 Middletown Press account of the company’s history notes that “Eventually, economies of scale…[forced]Thomas Jr.’s son Leon to stop distilling his own and …[he instead]bought from his cousin Edward Everett, Jr. By the 1940s, Edward cut off Leon.”

The T.N. Dickinson Company formed a partnership with American Distilling in East Hampton and began to once again distill witch hazel. In 1983, M.K. Laboratories bought the E. E. Dickinson Company and in 1997, in partnership with American Distilling, moved all production to East Hampton, thus bringing both branches of the Dickinson family witch hazel enterprise under one corporate ownership. American Distilling produces witch hazel under the name “Dickinson Brands,” bottling products bearing both the E.E. Dickinson “Yellow Label” and those with T.N. Dickinson’s blue label in their modernized plant. In 1997, the contents of the old Essex factory were sold at auction and the property placed on the market. A thoughtfully designed adaptive reuse of the landmark Art Deco building successfully redeveloped the 24,000- square-foot building as “Witch Hazel Works,” an office building.

What made Connecticut the center of the witch hazel world? Tom Shultas, a representative of American Distilling, feels that it was an accident of history. Witch hazel was produced in other states by other companies, but the Dickinson family had an early and very successful start. The raw material for witch hazel is cheap, plentiful, and local to Connecticut—all providing the state a big advantage. Even in the grip of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Dickinson family owned sailboats and yachts, as evidenced by photos and Christmas cards in a family scrapbook. Successive generations of Dickinsons were college educated and took a serious role in the company’s day-to-day management. By emphasizing quality in its national advertising and on the production line, Dickinson ensured that its product became a popular part of the American medicine cabinet. And by demonstrating corporate creativity in the face of changing markets, Dickinson has made its witch hazel an essential component of the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries’ products. The manufacturing of witch hazel is a Connecticut success story. Begun in the 19th century, it continues into the 21st, quietly putting Connecticut’s industrial prowess on display.

Mary M. Donohue was the survey and grants director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism. She’s written many articles for Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

For more articles on Connecticut’s fascinating medical history, see Spring 2007 and Feb/Mar/Apr 2004.