by Tracey Wilson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2013/14

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

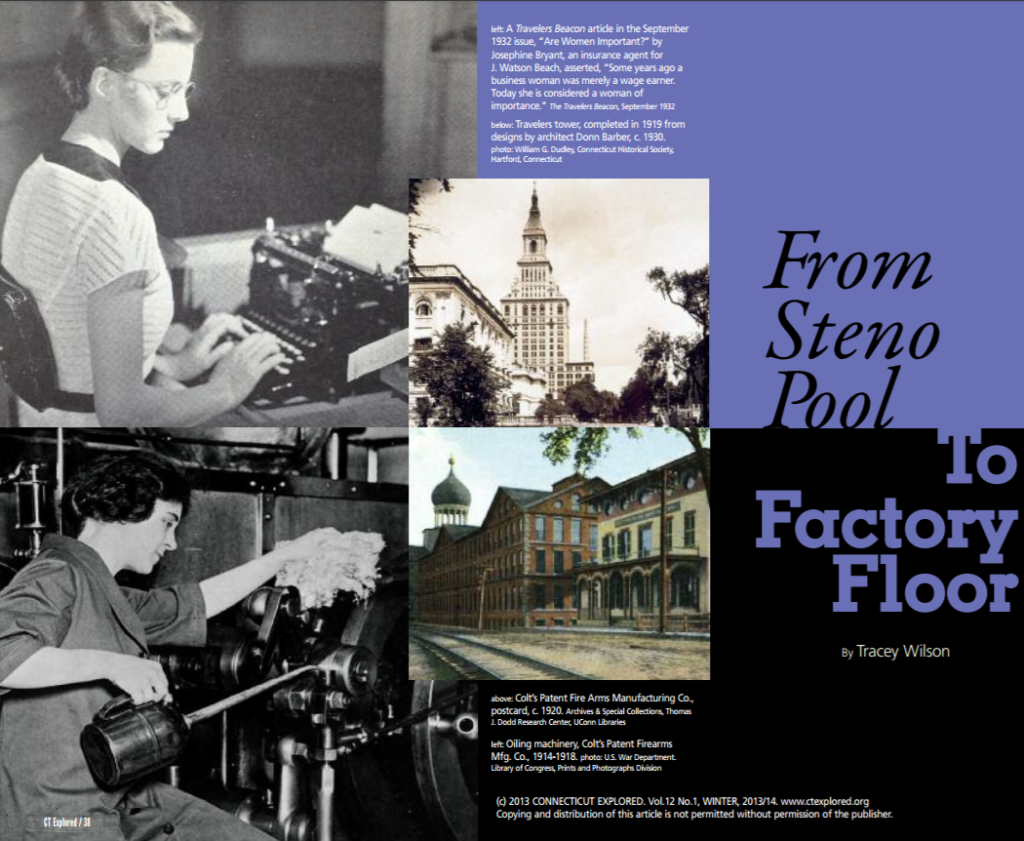

On her first day of work in 1915 at the Travelers Insurance Company, Lelah Avery of Cabot Street, Hartford, donned her most fashionable shirtwaist dress, a hat, and gloves to make her debut in the steno pool. To the young high school graduate, her department might have reminded her of the high-school typing class she had just completed; the desks stood in rows in a large room. The female supervisor guided her to her desk and showed her how to listen to the Ediphone recordings men dictated on the wax cylinders. Every hour runners brought fresh cylinders to one of the many steno departments in the company for transcription.

Young single women such as Avery saw insurance work as a step above work in a factory or a department store. Jobs in insurance paid better than domestic and sales work—even twice as much, at a salary of $12 per week.

Avery joined a workforce that was segregated according to gender, supervised by a woman, and run by men. Although the Travelers buildings, workforce, and business grew tremendously during the 20 years she worked there, the Yankee Protestant culture, a strict division of labor, and female workers’ second-class status prevailed.

On 26-year-old Emma Shepard’s first day across town at Colt’s Firearms, also in 1915, she walked the eight blocks to the factory from her Babcock Street home, where she was surrounded by German, French Canadian, Armenian, Irish, and Italian immigrant families. She proceeded to the women’s changing room, where she donned slacks, a work shirt, boots, and an apron. She did not work at Colt’s to sport the newest fashions; she knew comfort and safety took precedence.

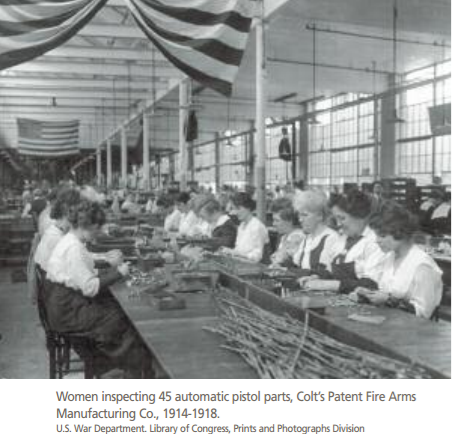

Tessie Sokolosky, who worked along side Shepard, said in my 1989 interview with her that a lead man and a set-up man would have guided Shepard through her first day. These men trained new workers, making sure they produced at an adequate rate and did not produce too many pieces of “scrap.” Each new worker was taught how to use a drill press, a milling machine, or a polishing machine or how to inspect parts. Shepard was taught to be an inspector using a snap gauge, a micrometer, and a spoon-check indicator.

Shepard spent her next 40 years at Colt’s, weathering the ups and downs of two world wars, the Great Depression, and the Korean conflict. Her blue-collar factory world, where she and other female workers always constituted a minority, gave women the opportunity to perform the same jobs as men, even if they did not make the same pay.

As business owners transformed their corporate organizations in the early part of the 20th century, women entered these companies in new jobs. At the Travelers, female stenographers, tabulators, and typists working on new machines helped revolutionize office work. At Colt’s Firearms, women’s entrance into gun making in the years before the U.S. got involved in World War I helped management wrest some control from unions and coincided with a more centralized management, diversification of company products, and new machine tools, which de-skilled jobs. Economic expansion during World War I coupled with the tremendous growth in Hartford’s population and economy defined a society in need of workers, which allowed women to enter new arenas of work.

Middle-class reformers who wanted to protect women questioned women’s entrance into these jobs, fearing that management would exploit them. Trade unionists resisted their employment because women, paid less than men, competed for jobs. But new personnel departments started to gain control of hiring, pushing aside the inside contract system under which unions hired workers. That opened the way for women, as many unions barred them from membership.

At the same time that so-called reformers and trade unionists questioned women’s place in certain industrial jobs, well-meaning advocates for women also challenged the propriety of having women work in insurance offices. Some claimed that a “woman’s nature” was more suited to domestic concerns and thought the business world would morally corrupt them. Muller v. Oregon (1908), which upheld Oregon state lawslimiting the work day to eight hours for women to protect their health, reinforced the idea that women needed to be protected in the workplace, and Progressive reformers challenged their rhetoric.

Despite these attitudes, women flocked to work. Between 1880 and 1920, the number of women in the Connecticut work force tripled, from 48,663 to 146,252. By 1920 almost one quarter of Connecticut’s women worked for wages outside the home, and more than one-quarter of the labor force was female.

This increase in the ranks of female workers led the state to collect information and, in true Progressive Era fashion, produce reports to document changes. Starting in the 1890s, the state Bureau of Labor Statistics bi-annually published “The Conditions of Wage Earning Women and Girls.” The report suggests that Hartford manufacturers willingly hired women in small numbers to work in machine shops, small arms manufacturing, and the Underwood and Royal typewriter factories. By 1910, almost one-third of the 48,991 women employed in manufacturing in the state worked in the manufacture of metals. Of those women, nearly one-quarter, or about 4,000, labored in firearms and ammunition factories such as Colt’s.

Manufacturing employed more women than any other occupation than domestic work in 1910 and clerical work every year after that. The percentage of Connecticut women in domestic service declined sharply, from 38 percent to 4 percent, between 1910 and 1960 as women increasingly chose clerical and manufacturing work over domestic service. This shift from domestic work to clerical and manufacturing work preceded a similartrend in the rest of the country. Clerical workers were not counted in 1900, but by 1960 they accounted for 41 percent of the female workforce. Most of these clerks worked in the state’s growing insurance companies.

By 1915, insurance companies strictly defined the type of woman appropriate for office work. Travelers management, for instance, only would hire young, single, white, Protestant, and native-born women. Not welcome in that company’s workplaces were Jews, Irish Catholics, or African Americans. Management wanted women with high school-but not college-education plus clerical training.

By 1915, insurance companies strictly defined the type of woman appropriate for office work. Travelers management, for instance, only would hire young, single, white, Protestant, and native-born women. Not welcome in that company’s workplaces were Jews, Irish Catholics, or African Americans. Management wanted women with high school-but not college-education plus clerical training.

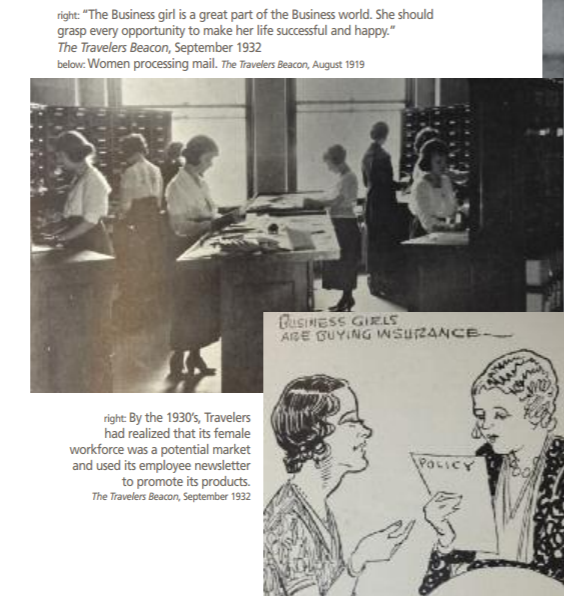

The Travelers “Home Office Census” of 1971 shows the number of home-office employees peaking at more than 5,800 in 1930, having grown from about 900 workersin 1913 to more than 3,000 in 1919. Business was booming. Between 1919 and 1927 the value of life insurance policiesissued quadrupled, from $1 billion to $4 billion. In 1925, Travelers wrote its first fire and inland marine policies. Travelers needed clerical workers to keep up with increased business.

New kinds of business machines operated by women made servicing insurance policies more efficient. The specialization of office jobs during the 1920s has been equated with the specialization of workers’ tasks on factory assembly lines. At Colt’s and Travelers alike, each worker played a small, discrete role within the larger whole. This was certainly efficient in both settings, but it fostered ignorance of other aspects of the business, reducing both sets of workers to cogs in the production wheel.

Lelah Avery’s experience exemplifies that situation. In her department, one woman ran the control board, assigning and collecting the wax cylinders and transcriptions. After being assigned a cylinder, stenographers such as Avery listened to the dictation on it through earphones and typed the contents. When finished, a stenographer took it back to the control board. Another woman measured the lines—in inches, with a cardboard ruler—and kept a tally for each worker. Just as at Colt’s, Travelers management held each worker accountable for the “pieces” of work she completed.

Regular typists worked across the aisle from the Ediphone operators. They produced letters and documents from written copy rather than from the cylinders. Their work, too, was measured with rulers.

The insurance company defined the operation of key-punch machines (introduced in the early 1900s) as “women’s” work. The company stored all accident claims, agent production, tardiness, absence, sickness, and vacation records on key-punch cards. In 1922, management spread the 120 key-punch operators among departments throughout the company. For the first time, these female workers were not segregated, though stenographers still were.

The ambitious woman who worked on typewriters, key-punch machines, and tabulators could advance in two possible ways. She could be promoted to supervisor of either a steno department ortabulating department, orshe could become a private secretary for a male executive. As a private secretary, she would take dictation, type, answer phones, and often help administer the department that the executive managed. The more powerful the executive, the higher the secretary’s status and pay. But she also became subject to the whims of her boss. No longer could she leave at the bell that released the stenographers at 4:00 p.m. Nor was the companionship of other women part of her daily routine.

Female employees at Travelers worked in a paternalistic system in which management sought to protect them and to make the company a “respectable” place to work by imposing a strict behavior code and a safe separation between men and women. Under the paternalistic guise of protecting workers, Travelers exerted strict discipline throughout the company. New hires were issued an “Office Regulations” pamphlet that spelled out the rules of the workplace. In the early 1920s, each day began with a warning bell that sounded five minutes before the beginning of the session. When the final bell rang, employees who were not at their desks were marked tardy. Absence and tardy slips went to the personnel office each day.

Managers watched workers in the hallways. They watched the clock at lunch and at quitting time. Management admonished workers not to go “to the lunch room or corridors before the bellrings at 12:15.” They punished women who broke the rules with detention hours and suspension from work with no pay. Interviews suggest that women found the rules too strict, controlling, and unfair and that they led to fear among the workers. Unlike in factories where workers might gain a sense of solidarity, at Travelers, the women had very little control over their day.

Minnie V. Stevens supervised all the steno departments at Travelers in the 1920s and 1930s. Female workers such as Eleanor Boyle and Mary Seymour, whom I interviewed, said they feared her more than they feared male supervisors; she was viewed as being arbitrary, and she was known to reduce her workers to tears. The legions of women under her direction could not talk to one another while at work. They could only leave their desks to get a new cylinder or go to the bathroom. Supervisors like Stevens even checked the bathrooms if a woman tarried too long.

Colt’s hired a different group of women for jobs that had a distinctly “working class” flavor. These women were married and single, gentile and Jew, immigrant and native-born, though African American women were excluded until after World War lI. Their jobs did not require skills learned at school. Colt’s was a blue-collar workplace replete with dirt, noise, bells, and, by the 1930s, collective action organized by unions against management. Colt’s management hired women to perform work that offered sporadic employment and little chance for advancement.

Though there was some gender separation, many men and women worked side by side doing the same job. Workers were often loyal to the company, but they frequently saw their interests and those of the company a s conflicting. Unlike the Travelers, Colt’s management did not see it as their role to “protect” women who worked there. And though women could not join many craft unions until the 1930s, they still knew about unions, which challenged the paternalism and power of the management.

For women working at Colt’s, confrontation with management was much more acceptable than it was for women working at Travelers. As a business, production of guns was characterized by frequent layoffs and rehires and struggles over workplace control. It was not unusual for workers to unite and confront management. This heterogeneous group of women joined together in ways that women at Travelers never imagined.

In October 1918, male and female Colt’s workers struck for the Eight-Hour Day, a 48-hour week, and an end to the bonus system. By October’s end, according to The Hartford Courant, the War Labor Board, established to settle labor disputes, backed the workers. The arbiter increased the basic hourly wage for women to 32 cents per hour and for men to 42 cents per hour and abolished the bonus system. Colt’s female workers received 25 percent more than the average Travelers female clerk made at this time, according to Charlotte Holloway in the 1915 government publication “Report of the Bureau of Labor on the Conditions of Wage Earning Women and Girls in Connecticut.“

In the months following the end of World War I, the number of Colt’s workers dropped precipitously from 10,000 to about 800. The company vacated more than 100,000 square feet of factory space. But Colt’s subsequent retooling and diversification provided female workers with different kinds of job opportunities. In 1922, Colt’s purchased The Johns-Pratt Company, a maker of compressed asbestos products. Colt’s also bought the Autosan Company, which made commercial dish washing machines, and Noark Electrical, a producer of heavy industrial safety switches, meter entrances witches, motor control equipment, fuses, service equipment, circuit breakers, and panel boards.

In the months following the end of World War I, the number of Colt’s workers dropped precipitously from 10,000 to about 800. The company vacated more than 100,000 square feet of factory space. But Colt’s subsequent retooling and diversification provided female workers with different kinds of job opportunities. In 1922, Colt’s purchased The Johns-Pratt Company, a maker of compressed asbestos products. Colt’s also bought the Autosan Company, which made commercial dish washing machines, and Noark Electrical, a producer of heavy industrial safety switches, meter entrances witches, motor control equipment, fuses, service equipment, circuit breakers, and panel boards.

A 1936 pamphlet published by Colt’s for its employees, “This is Your Company,” described Colt’s new acquisitions. Noark became the plastics division at Colt’s, making newly invented molded plastic products including buttons, buckles, molded slides, garment trimmings, brake linings, and sheet packing. In these acquisitions, Colt’s took over not just the factories and equipment but the workforces, too. Noark, also based in Hartford, employed only women in its plastics division, a whole new area of manufacturing that men and unions did not control. Noark women made toothpaste-tube caps, four-way electrical plugs, and molded tobacco, cigarette, and cigar containers. The women working in plastics were paid less than those making firearms. As at Travelers, a “forelady” supervised the division, and workers considered her to be more exacting than the foremen.

Not surprisingly, tension over pay and working conditions developed between the women working in plastics and those producing firearms. While 90 percent of the gun-making work force was laid off after the war, those women who held their jobs retained the higher pay. After the recession of the early 1920s, the gun division enjoyed some growth through selling arms to Chile. Some women, such as inspector Emma Shepard, who worked alongside men in firearms, drilling, polishing, inspecting, and grinding barrels during the war, retained their positions through the 1920s.

Working in either blue-or-white-collar settings provided women a sense of financial independence and an identity outside of the family. It also gave them opportunity to learn skills and interact with peer groups. These women who worked in large factories and insurance companies widened women’s sphere and helped to break through then arrow stereotype that women were only suited to certain occupations (they had, after all, been working in small shops, as domestics, and other occupations for a very long time), opening doors for women in the latter half of the 20th century. Not until the 1963 Equal Pay Act and the 1964 Civil Rights Act did women gain the legal rights to equal pay for equal work and access to all jobs. Labor unions opened up to women, and reform organization such as the National Organization for Women (formed in 1966) stood up for women workers’ legal rights.

Happily, gone are the paternalistic days of the steno pool. But equality in the workplace has not yet been achieved. Women are well-represented today in white-collar management but have yet to achieve parity with men in pay and in representation as CEOs and presidents, and they still only hold 27 percent of manufacturing jobs.

Tracey Wilson is town historian for the Town of West Hartford.

Explore!

Read more stories about Work in Connecticut on out TOPICS page.