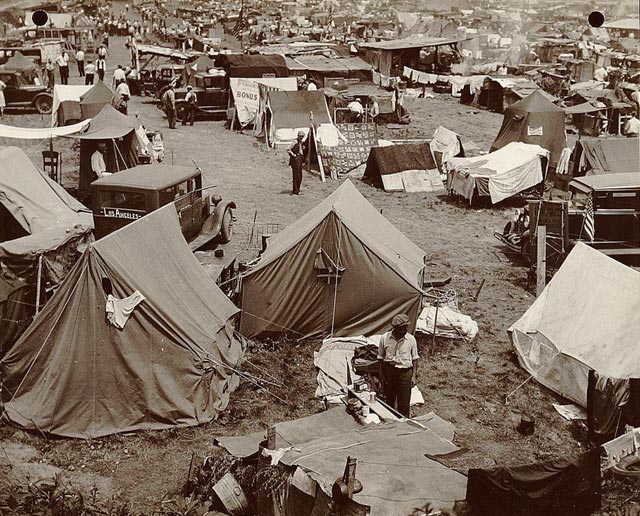

Veterans demonstrate in Washington, D.C. for early distribution of the “bonus” pension, April 8, 1932. photo: Underwood and Underwood, Library of Congress

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Spring 2017

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

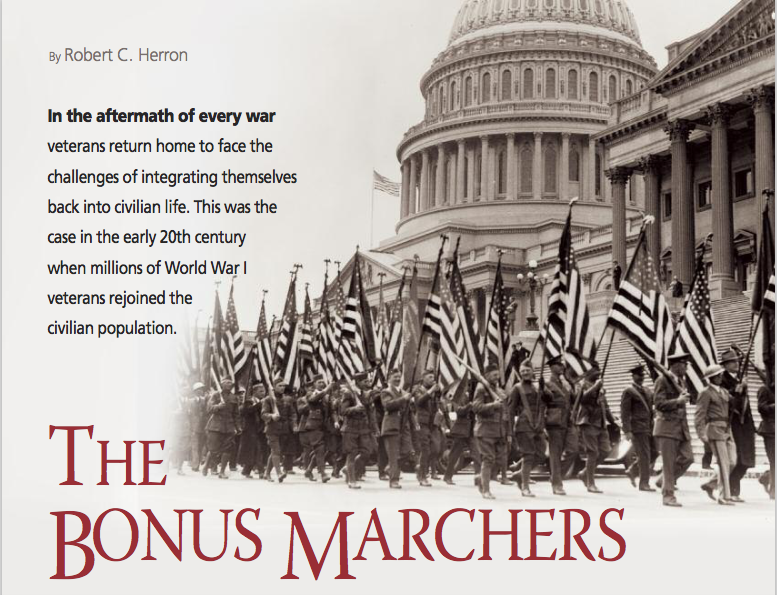

When the veterans returned home, most were able to reestablish themselves in the boom times of the 1920s. But for many, financial security was tenuous, especially after the advent of the Great Depression. These veterans had been promised the support of “a grateful nation,” but when they called on that support they found doors closed to them. They asserted themselves aggressively to claim what they considered their rights. The result would be radical changes to the way “a grateful nation” provides for its veterans.

The Fitch’s Home for Soldiers and Their Orphans

The Fitch’s Home for Soldiers and Their Orphans was founded on July 4, 1864 in the Noroton Heights section of Darien. It was intended for the care of disabled Civil War veterans and the orphans of Civil War soldiers who had been killed in the war. Established by Benjamin Fitch, a Darien philanthropist, in its early years the facility’s focus was on orphans. It was built at a time when petitioning for assistance was considered an admission of failure, and few veterans were willing to live with that disgrace.

Benjamin Fitch died in 1883 and left an endowment for the upkeep of the home. Even with this support, however, the condition of the home deteriorated. By 1888 the State of Connecticut assumed responsibility for its operations. By then the orphans had grown up and moved out. The remaining population was small and manageable, comprised mostly of a few veterans of the Civil War, the wars against Native Americans, the Spanish-American War, the Mexican Punitive Expedition, the Philippine Insurrection, and the small conflicts in the Caribbean and Central America. To the institution’s credit, at a time of rampant racism, a significant number of veterans at Fitch’s were African Americans. They had served as “Buffalo Soldiers” (a term used for those who fought on the western frontier), and with “Black Jack” Pershing, who led African American troops during the Spanish-American War, and would later become commander of American forces during World War I.

By the early 20th century Fitch’s Home had become an integral part of the Darien community. Veterans living there participated in town parades, while local volunteer organizations performed various services for the home.

In 1920, 250 veterans lived at the home. Life was simple and orderly. Nobody seems to have anticipated the tsunami of World War I veterans that was about to overtake the facility.

World War I resulted in a large influx of veterans. Many suffered from disabilities that weren’t recognized at the time. Conditions such as mental-health issues, substance

addiction, and post-traumatic stress syndrome (unless it manifested itself as overt and disturbing behaviors that were categorized as “shell shock”) weren’t treated as disabilities in the early 20th century. Criteria for admission to Fitch’s Home were usually limited to physical impairment. Even so, a substantial number of veterans applied and were admitted. In 1929, at the start of the Great Depression, Fitch’s Home housed 217 veterans.

The Bonus Army

In 1924, with patriotic fervor at its peak and the economy booming, the United States Congress decided to provide a pension for those who had served in the military. The fund was to accrue interest and become payable in 1945.

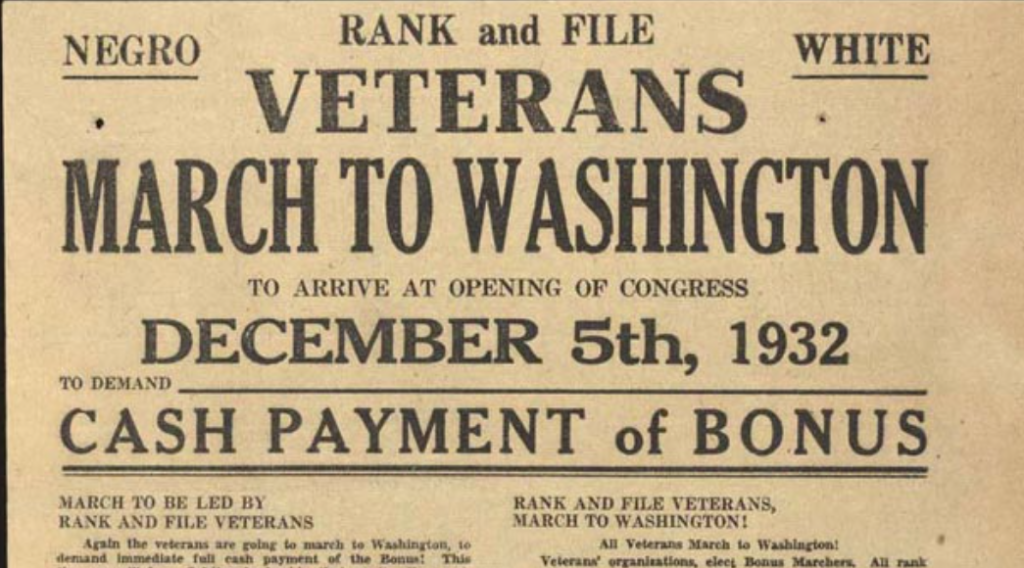

Poster (broadside) published in New York advertising a demonstration in Washington on December 5, 1932. Congress finally acted in 1936. Veterans Central Rank & File Committee, Library of Congress

The Great Depression put otherwise productive men out of work, including many veterans. The term used for these people was “Forgotten Man.” Songs and movies of the era, now viewable on youtube.com, provide a sense of the passion and emotion the public felt for these men. Songs such as “My Forgotten Man” and “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” and films such as “Wild Boys of the Road,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” and “My Man Godfrey” capture the desperation of the times. The public wanted to help, but, given the lack of economic resources available, struggled to do so.

Destitute veterans felt the bonus money should be released immediately. A movement began to pressure the federal government to pay out the bonus. In spring 1932, 17,000 WWI veterans and their families—including at least 25 veterans from Connecticut—converged on Washington, D.C. and set up a camp of shacks at Anacostia Flats. They hoped to sway public opinion and pressure the U.S. Congress to approve early distribution of the bonuses. The press and the public called these veterans the Bonus Army.

Bonus Expeditionary Forces encampment, Anacostia Flats, Washington, D.C., 1932. photo: Theodor Horydczak, Library of Congress

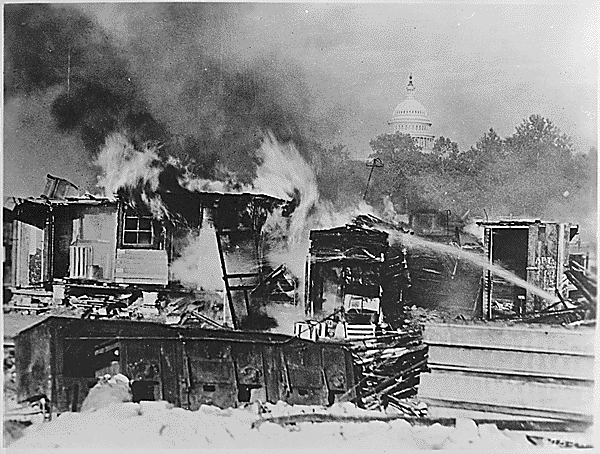

Unfortunately, the gathering in Washington caused a backlash of negative public opinion toward the veterans. A powerful bloc mobilized to paint these veterans as slackers and subversives. Congress rejected the notion of paying the bonuses early. On July 7, 1932 the U.S. attorney general ordered the veterans removed from government property. The D.C. police used force. When the Bonus Army reoccupied the site, the police opened fire, killing two veterans. President Hoover ordered the army to clear the site. General Douglas McArthur, exceeding his authority, ordered a cavalry charge followed by a bayonet and tear gas attack supported by six tanks. President Hoover ordered a halt, but McArthur continued, dispersing the veterans, wounding 55 of them, jailing 135, killing one pregnant woman, and burning the shacks the marchers lived in. There was a substantial public outcry over the brutality of this assault and widespread public sympathy for the veterans.

Bonus Army shacks at Anocostia Flats, Washington, D.C., burning after the battle with the military, July 1932. photo: Department of Defense, National Archives

The Bonus Marchers and Rocky Hill

On August 7, 1932, the 25 Connecticut refugees from the Bonus March arrived home from Anacostia. Sympathy for them was high. The Fitch’s facility was unable to absorb this new wave of veterans. The men were sent to the Veteran’s Supply Farm in Rocky Hill. The Rocky Hill Supply Farm, which had been owned by the Hartford Retreat, a privately owned, state-regulated mental facility, and which provided dairy products and produce to the retreat, had been acquired January 4, 1932. There was no room for them in the few available buildings there, either, so they were housed in tents and fed from a mobile kitchen provided by the Connecticut National Guard. The question was: what would the state do with these people in the long term?

A plan was proposed to Governor Wilbur Cross to build a new home at the supply farm for able-bodied veterans in need modeled on the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. The governor rejected the idea, arguing that, “The proper care of veterans needing relief is a duty of the state. … At Rocky Hill, all who need care can get it—not as charity, but as an expression of Connecticut’s appreciation to the services of the veterans.” This marked a change in the mission of the state veterans’ homes from the care of disabled veterans and orphans to provision of relief to veterans in need.

By 1936 there were more than 1,000 veterans in the two facilities. Overcrowding at Fitch’s had become untenable. Cots were set up wherever there was room, including in the chapel, where they had to be removed on Sundays for services.

In 1936 Congress reversed itself and authorized immediate payment of the bonuses. It was expected that the payments would induce veterans to leave the homes. However, there is an old military expression, “You eat a lot of beans on the outside.” Few veterans were anxious to leave. Word that there was a haven for veterans at Rocky Hill spread rapidly, and more veterans were entering the homes than were leaving.

It was clear that a solution more permanent than tents and mobile kitchens was called for. Plans were solicited for a new veteran’s home. After years of political jockeying, in 1936 it was agreed that Fitch’s Home had to be remodeled or replaced.

The location of veterans’ facilities was a hot-button issue in the 1930s. There was intense competition among towns for sources of revenue and jobs that visitors, suppliers, and other support organizations might provide. The opening of a veterans’ hospital in Newington in 1931 is a case in point. Competition to host the hospital was keen between Windsor, New Haven, and Newington. Newington won out because it was located in the center of the state and was easily accessible from many locations.

The competing sites for a new veterans’ home to replace Fitch’s were Darien, West Haven, and Rocky Hill. West Haven leaders wanted the new home because it was the site of a veterans’ tuberculosis hospital that they hoped to expand. Greenwich County politicians fought to keep the facility where it was. Fitch’s Home had been a part of the community since 1865.

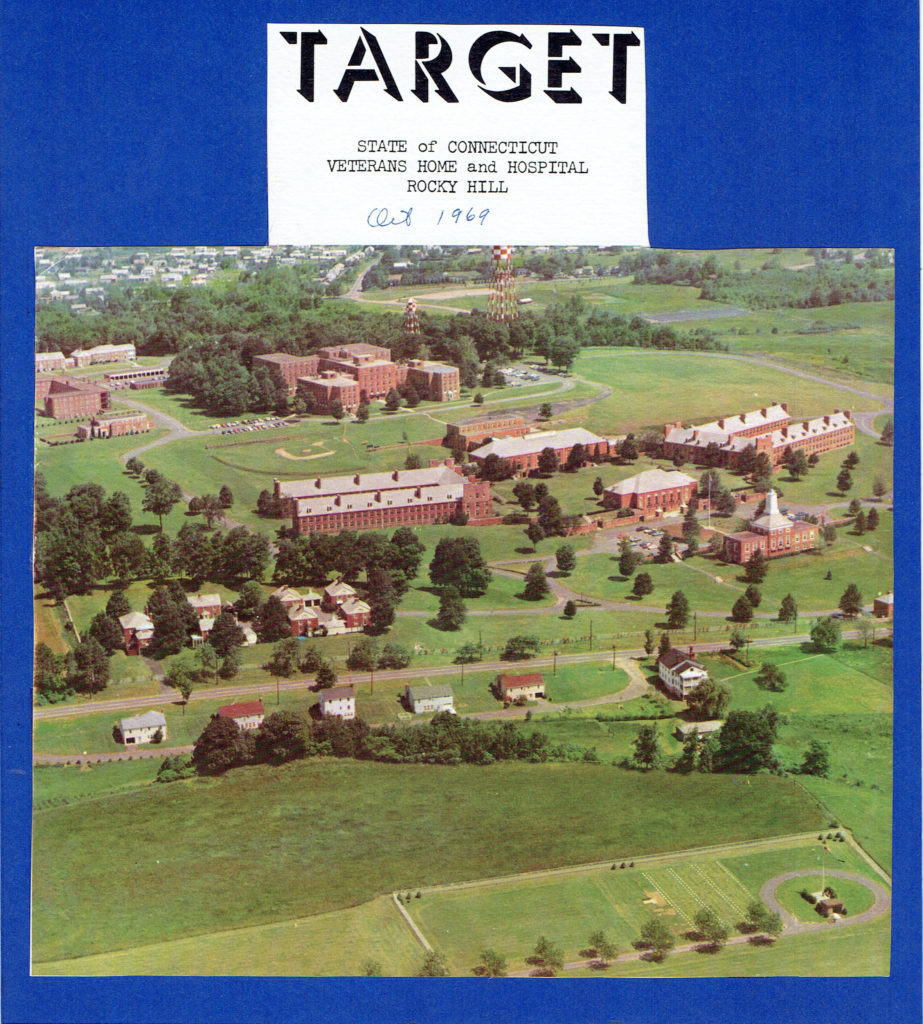

Veterans Home and Hospital, Rocky Hill, 1969. Target, courtesy of Mike Martino, Rocky Hill Remembered Collection

When the dust settled, Rocky Hill emerged the winner. The existing Rocky Hill facility was modern, while the Darien facility was showing its age. Rocky Hill was located in the center of the state, and it was in close proximity to the Newington Veterans Hospital.

The veterans moved out of Fitch’s Home on August 28, 1940, departing from Darien’s Noroton train station on a special train of four coaches and two baggage cars. After arriving at the Rocky Hill station, the men were then bused to the new facility at 287 West Street.

The numbers of veterans in the system in 1940 dramatizes the impact of World War I on the Connecticut veterans’ system. Before the move, the 1,000 veterans at Rocky Hill were primarily from World War I. The veterans from Fitch’s added 1 Civil War veteran, 1 from the Indian Wars, 50 from the Spanish-American War, 10 from the Mexican Expedition, and 499 from World War I. Now there were 63 veterans from earlier wars and more than 1,500 World War I veterans.

The Veterans Home Today

The Rocky Hill facility originally comprised only the supply farm. In 1940 the Gilbert Family of Rocky Hill sold 150 additional acres to the state. In 1968, 60 acres of this land were given to the Town of Rocky Hill by the Connecticut General Assembly for the formation of Dinosaur State Park. Some of the remaining land contains the Raymond F. Gates Cemetery for veterans and housing for staff.

The current home is made up of 40 red-brick buildings on land acquired from the Gilberts. Its mission evolved based on the influx of WWI veterans. As wars became more frequent and with an ever-larger standing military, the demand for veterans’ services has continued to increase and the mission has continued to evolve. The home has evolved from a haven for a handful of disabled Civil War veterans and orphans to a large chronic-disease treatment center for veterans of several wars.

Robert Herron is the historian at the Rocky Hill Historical Society. This article is based on Rocky Hill in World War I (Service Press, 2016), co-sponsored by Cora Belden Library/Rocky Hill Historical Society.