by Richard A. Kissel

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. WINTER 2016/17

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

As its heavy wheels slowly came to rest, the train carriage could retain its guest no longer. The gentleman’s heel greeted the earth and anticipation carried his stride. His patience was rewarded. Awaiting him was a collection of small, curious bones, presented to him in a hat by the station’s master. He accepted it and was back on the train in a flash. With the sound of a whistle the train pulled away, returning east with its newly acquired fossil passengers. Millions of years ago the creatures whose fossils these represented were driven by hunger and hooves; steam and rail carried them this day. Their new caretaker—Yale’s Othniel Charles Marsh—must’ve been delighted. Anticipation turned to satisfaction that day in 1868. Passion and obsession would soon follow.

Nearly seven decades earlier, in 1801, Yale College President Timothy Dwight offered Benjamin Silliman the school’s first professorship of science. Still in its infancy on American shores, science was challenging citizens to view the world through observation and inference—to find explanations for the world’s phenomena that were rooted in nature, not just faith. Silliman knew little of science when he accepted Dwight’s offer, but he soon established himself as the father of American science. Among his many contributions was the chemical analysis and published documentation of a meteorite that fell in 1807—the first documented fall in the new world. (See “Connecticut Catches a Falling Star,” Winter 2007-2008.)

In 1856 aspiring freshman and amateur mineralogist Othniel C. Marsh successfully completed Yale’s admission exam, attracted to the university by Silliman’s work. Ten years later Marsh convinced his uncle and financier George Peabody to dedicate funds for a grand natural history museum at Yale, and the Peabody Museum of Natural History was born. That same year Marsh was appointed as Yale’s professor of paleontology, the first position of its kind in the country.

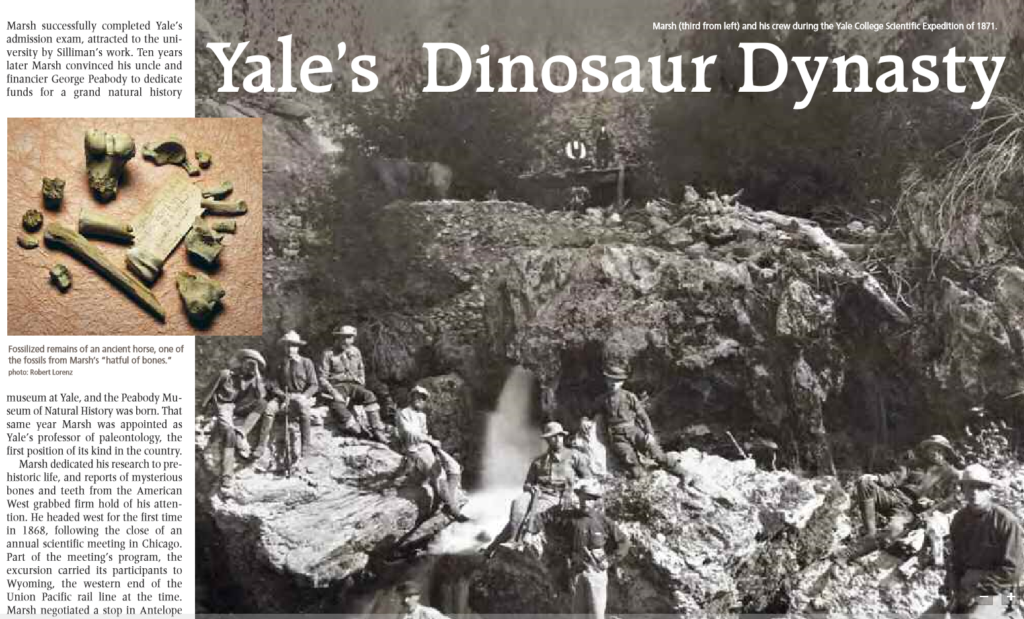

Marsh dedicated his research to prehistoric life, and reports of mysterious bones and teeth from the American West grabbed firm hold of his attention. He headed west for the first time in 1868, following the close of an annual scientific meeting in Chicago. Part of the meeting’s program, the excursion carried its participants to Wyoming, the western end of the Union Pacific rail line at the time. Marsh negotiated a stop in Antelope Station, Nebraska, where the fossil remains of tigers, elephants, and humans had been reported. He quickly found the excavated well from which the bones had been recovered and sifted through the rock pile. Hurried by the train’s schedule, he asked the stationmaster that more be collected for him. Upon his return, as the train headed back east, Marsh’s hatful of bones was handed to him. His collection of fossils for his new museum had begun.

These fossils—Leidy’s broken dinosaur teeth and now Marsh’s hatful of bones—represented the promise of more to come: endless miles of undisturbed, fossil-rich strata. From these sandstones and mudstones would come a parade of massive skeletons that would, over the course of coming decades, fill the halls of museums across the nation.

BUFFALO & BRONTOSAURS

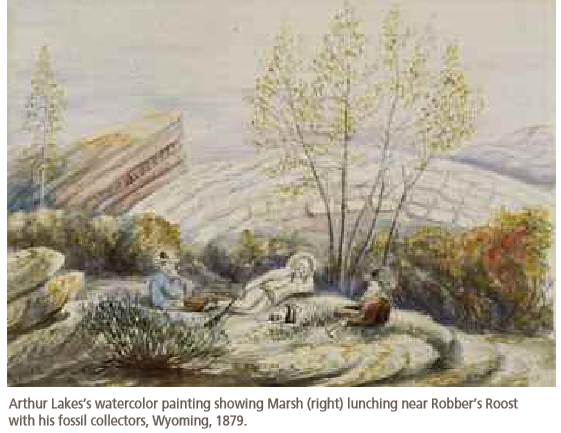

Marsh led his first expedition to the American West in 1870. The first of four Yale College Scientific Expeditions was made up of Yale students and supported by military escorts—famously including “Buffalo Bill” Cody, at least for one day. The nearly six-month expedition was ambitious, stretching across Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado, and Kansas. There was even time for sightseeing in Salt Lake City and San Francisco. But Marsh’s ambition was rewarded. The team uncovered fossils of ancient rhinoceroses and rodents, and dinosaur-aged fossils of great flying reptiles. This first excursion was as successful as Marsh had hoped, and he followed up with expeditions in each of the following three years.

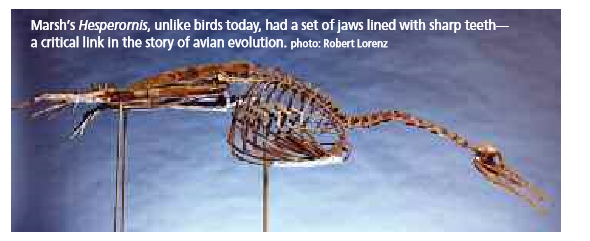

Among the extinct creatures recovered from these expeditions were the primitive birds Hesperornis and Ichthyornis, named by Marsh in 1872 and 1873. Unlike modern birds, Hesperornis and Ichthyornis had jaws lined with sharp, pointed teeth. This trait was a direct link to birds’ reptilian ancestry and an early connection to dinosaurs—an idea being promoted across the Atlantic by Marsh’s contemporary and English biologist Thomas H. Huxley. Known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his vocal support of the theory of evolution by means of natural selection, Huxley was soon impressed with Marsh’s discoveries in the American West, and in 1876 he visited Marsh in New Haven. Together, the two pored over Marsh’s fossils of early horses and soon reconstructed a 50-million-year evolutionary history of the lineage, beginning with the early, dog-sized forms that once roamed North America.

Marsh’s toothed birds, tiny horses, and others in his prehistoric menagerie also drew recognition from Charles Darwin. Today the Peabody’s archives hold a letter from Darwin dated August 21, 1880, in which—in fewer than 100 words—Darwin recognizes Marsh’s discoveries as “the best support to the theory of evolution, which has appeared within the last 20 years.” Drafted 21 years after the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species, and a mere two years before Darwin’s death, the letter assigned an unparalleled importance to Marsh’s ever-growing collection—the Peabody’s collection—of fossil bones and teeth.

The collection grew as Marsh turned his attention to dinosaurs. From 1877 to 1889 Marsh had described and named the now-iconic Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops, and Brontosaurus. And though T. rex would be named six years after Marsh’s death, based on a semi-complete skeleton recovered by the American Museum of Natural History, the first fossil of T. rex ever collected was recovered in 1874 and sent to Marsh at the Peabody. That the fossil—a single tooth—didn’t receive study at the time is no doubt a consequence of the sheer volume of material arriving in New Haven during that period. With 20-foot stegosaurs and 70-foot brontosaurs demanding attention, the specimen was easily overlooked—a tooth in a haystack of skeletons.

With Marsh’s discoveries leading the field of American paleontology, the world of the dinosaur was coming to life. Dinosaur bones, long turned to stone, told of ancient worlds like no other. One hundred and fifty million years ago, herds of long-necked brontosaurs thundered across the American West, while the beautifully grotesque Stegosaurus flashed its massive plates, protecting itself from the Allosaurus with its spiked tail. The Jurassic period of North America was the stuff of dreams and nightmares, and Marsh was its greatest author.

With Marsh’s discoveries leading the field of American paleontology, the world of the dinosaur was coming to life. Dinosaur bones, long turned to stone, told of ancient worlds like no other. One hundred and fifty million years ago, herds of long-necked brontosaurs thundered across the American West, while the beautifully grotesque Stegosaurus flashed its massive plates, protecting itself from the Allosaurus with its spiked tail. The Jurassic period of North America was the stuff of dreams and nightmares, and Marsh was its greatest author.

THE HOUSE THAT MARSH BUILT

Ten years after the Peabody Museum’s founding in 1866, the first Peabody building opened in the heart of Yale’s campus, a few blocks away from its current location. Initial plans called for a sprawling, impressive structure, but only one wing was built. As the Peabody’s collection grew to exceed the building’s capacity—in part due to the massive skeletons that had been accumulated by Marsh and his crews—the building was demolished in 1917, 18 years after Marsh’s death and during the third year of World War I.

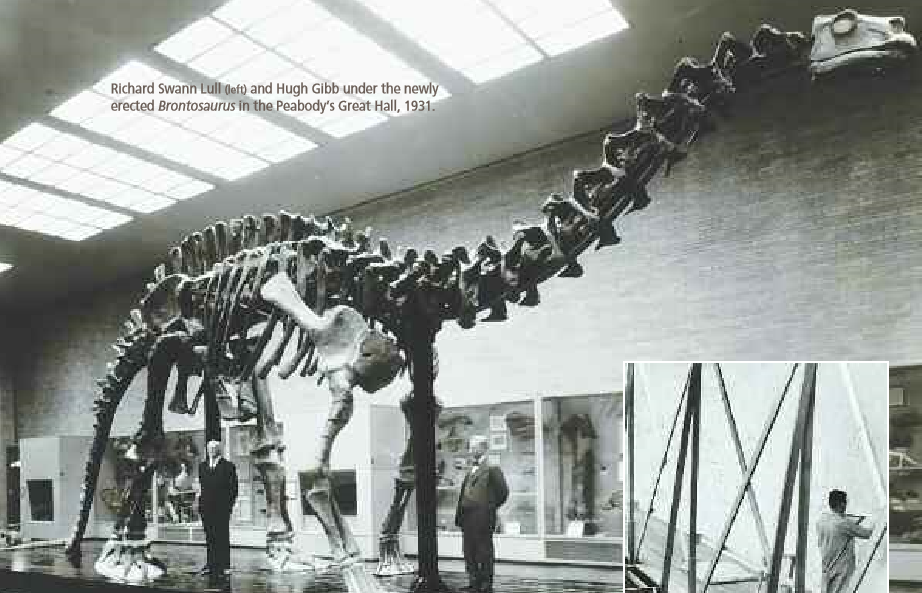

The second and current Peabody Museum was dedicated in December 1925, opening its doors to the public early the following year. Under the direction of paleontologist Richard Swann Lull, the new museum would breathe new life, so to speak, into Marsh’s dinosaurs. Not only was the museum’s Great Hall designed with these titanic skeletons in mind, Lull, a recognized educator and supporter of evolution, placed them in a context through which they’d never been viewed publicly.

Following Lull’s vision, the museum’s first floor was designed to tell the incredible story of evolution. After passing through the building’s entrance—at the base of a 93-foot tower of brick and sandstone—visitors were taken on a journey that presented, as stated in the museum’s 1927 exhibition guide, “the steady progression of life upward, from small, comparatively simple animals without backbones, through fishes, reptiles, and birds, to mammals, culminating in man: in other words, the process known as Organic Evolution.” Displayed in this context, Marsh’s dinosaurs served a new purpose. While their bizarre forms and absurd frames were—and still are—enough to dazzle, their role within Lull’s grand story only enhanced their presentation. In 1931 steel and wood created an armature for a new addition to the museum’s Great Hall; this massive frame would now support Marsh’s most famous skeleton: Brontosaurus.

In 1941 Rudolph F. Zallinger was a senior in Yale’s School of Fine Arts. That year he worked with Peabody director Albert Parr—a professor of oceanography at Yale who inherited the position from Lull in 1938—to illustrate subjects of Parr’s research. In the course of conversation, it was decided that the Great Hall, filled with grey bones set against unremarkable brick walls, was in dire need of color. As Zallinger recalled, Parr “thought it ought to be spruced up.” They conceived of an epic mural depicting 300 million years of evolutionary change—of both leaf and beast—across a 110-foot span. After an intense, six-month period of study, Zallinger began his work in 1943 as war raged beyond America’s shores, finishing his masterpiece in 1947 at the dawn of the nuclear age.

Zallinger’s mural presented Marsh’s dinosaurs in an even greater context. While Lull’s galleries presented a zoo of evolutionary highlights, Zallinger offered a safari. No longer were Marsh’s skeletons seen as isolated individuals surrounded by brick and concrete; rather, museum visitors were now transported to a fully realized prehistoric world—as best we knew it—thriving with ancient plants, giant insects, raging volcanoes, and, of course, Marsh’s dinosaurs.

In September 1953, thousands of households opened the pages of Life magazine to a multi-page reproduction of Zallinger’s study for The Age of Reptiles. The fossils and talents of Marsh, Lull, and Zallinger had joined to tell the epic story of global and evolutionary change. Such is the path of science. New ideas are built upon old, providing humanity with an increasingly refined understanding of the planet we call home.

QUILLS FOR THRILLS

Not long after Marsh’s death, the notion that birds’ ancestry was related to dinosaurs fell out of favor. Their connection to reptiles was still promoted, but birds were now thought to have evolved from a stock other than the Dinosauria—a notion that persisted through much of the early and mid-20th century. But much like Marsh’s early discoveries, the world of paleontology would once again enter a new era, and once again New Haven would find itself at the front of this change.

Not long after Marsh’s death, the notion that birds’ ancestry was related to dinosaurs fell out of favor. Their connection to reptiles was still promoted, but birds were now thought to have evolved from a stock other than the Dinosauria—a notion that persisted through much of the early and mid-20th century. But much like Marsh’s early discoveries, the world of paleontology would once again enter a new era, and once again New Haven would find itself at the front of this change.

In 1969 Yale paleontologist and Peabody curator John Ostrom named a new dinosaur that he had discovered a few years earlier in the hills of Montana: Deinonychus. With a total length of 10 feet—minuscule next to Marsh’s Brontosaurus—Deinonychus single-handedly changed our perception of dinosaurs. Dinosaurs had been considered, essentially, overgrown lizards—and unsuccessful ones at that. They were thought to be drab, slow, and lacking any complex behavior. But the skeletal frame of Deinonychus suggested something else. With a long stiffened tail for balance and lethal, sickle-like claws on its feet, the anatomy of Deinonychus was that of an active predator. Further, evidence at the time suggested pack hunting, a behavior requiring coordination and cooperation. The concept of Deinonychus as an intelligent, swift animal shook the paleontological world to its core, beginning what paleontologists today know as the dinosaur renaissance of the late 20th century. That dinosaurs are seen today as complex, active beasts originated with Ostrom’s little Deinonychus. Textbooks across the world were forced into revision.

This alone would define any scientific career, but Ostrom’s detailed analysis of the pelvic, shoulder, and wrist bones of Deinonychus led to yet another revolution. Comparing the fossil bones of Archaeopteryx, the oldest known bird, to Deinonychus, Ostrom discovered a suite of similarities. Deinonychus revealed in a greater detail than had been known the deep evolutionary connection between birds and dinosaurs. This idea—first proposed in the days of Marsh—did not resurface without controversy. Bitter disputes raged throughout the late 20th century. But with the discovery in the 1990s of beautifully complete dinosaur fossils preserved with feathers—including more recently a 30-foot-long tyrannosaur that’s covered in feathers from snout to tail—the evidence is undeniable. By the time of Ostrom’s death in 2005, paleontologists across the globe had overwhelmingly agreed: birds are dinosaurs.

YALE’S CONTINUNG LEGACY

The term Dinosauria was coined by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, just 22 years before the founding of Yale’s Peabody Museum. By the close of the 19th century, Marsh and his team had introduced the world to a fantastic assembly of prehistoric beasts from the badlands of the American West—many of which remain household names today. The impact of Yale would continue into the 20th century. Richard Swann Lull presented these creatures in their proper evolutionary context, Rudy Zallinger brought them to Life and into living rooms across the nation, and John Ostrom revolutionized our view and—every time we see a robin, hawk, or turkey—our personal connection to animals long thought vanished.

In New Haven today, within the walls of the Peabody and surrounding labs at Yale, Jacques Gauthier continues to refine the evolutionary history of dinosaurs and other reptiles. Rick Prum and Derek Briggs’s work on fossil feathers is showing dinosaurs’ true colors for the very first time, and Bhart-Anjan Bhullar is documenting the genetic underpinnings of birds’ evolution from dinosaurs. A glorious past is leading to an even more brilliant future. And  as children and students step into the doors of the Peabody today, turning the corner and craning

as children and students step into the doors of the Peabody today, turning the corner and craning

their necks upward in awe of Brontosaurus, tomorrow’s scientists are born. What discoveries will they make?

Richard Kissel is a vertebrate paleontologist and the director of public programs at Yale’s Peabody Museum, where he oversees exhibitions and education.

Except where noted, all images courtesy of the Peabody Museum Archives.